Nothing special, just history, drawings of historical figures in some… er… non-canonical relationships and fun! 🥂25 year old RussianHe/him

258 posts

Chuckling Giggling Hehing Cause These Two Separately And Unconnectedly Drawn Pictures Look Like:

chuckling giggling hehing cause these two separately and unconnectedly drawn pictures look like:

"you're just a little hater"

"and?"

put together

-

spaceravioli2 liked this · 1 year ago

spaceravioli2 liked this · 1 year ago -

tr-colorstealer liked this · 1 year ago

tr-colorstealer liked this · 1 year ago -

1ll-def1ned liked this · 1 year ago

1ll-def1ned liked this · 1 year ago -

elderfrogboy liked this · 1 year ago

elderfrogboy liked this · 1 year ago -

kaxen reblogged this · 1 year ago

kaxen reblogged this · 1 year ago -

kaxen liked this · 1 year ago

kaxen liked this · 1 year ago -

cerumilla liked this · 1 year ago

cerumilla liked this · 1 year ago -

v444414j liked this · 2 years ago

v444414j liked this · 2 years ago -

cherrepachka liked this · 2 years ago

cherrepachka liked this · 2 years ago -

pizza-hats-of-the-world-1882 liked this · 2 years ago

pizza-hats-of-the-world-1882 liked this · 2 years ago -

asdeadasasquirrel liked this · 2 years ago

asdeadasasquirrel liked this · 2 years ago -

clove-pinks liked this · 2 years ago

clove-pinks liked this · 2 years ago -

lordansketil reblogged this · 2 years ago

lordansketil reblogged this · 2 years ago -

lordansketil liked this · 2 years ago

lordansketil liked this · 2 years ago -

bringmebacktothe18thcentury liked this · 2 years ago

bringmebacktothe18thcentury liked this · 2 years ago -

empirearchives liked this · 2 years ago

empirearchives liked this · 2 years ago -

gamersix06 liked this · 2 years ago

gamersix06 liked this · 2 years ago -

hesperus-imperator liked this · 2 years ago

hesperus-imperator liked this · 2 years ago -

koda-friedrich reblogged this · 2 years ago

koda-friedrich reblogged this · 2 years ago -

koda-friedrich liked this · 2 years ago

koda-friedrich liked this · 2 years ago -

usergreenpixel liked this · 2 years ago

usergreenpixel liked this · 2 years ago -

count-lero reblogged this · 2 years ago

count-lero reblogged this · 2 years ago -

count-lero liked this · 2 years ago

count-lero liked this · 2 years ago -

acrossthewavesoftime liked this · 2 years ago

acrossthewavesoftime liked this · 2 years ago

More Posts from Count-lero

Ney wearing a banyan and my headcanon about his glasses👓✨

Metternich: Remember when you said you weren’t going to interfere with my love life?

Wellington, after setting up a date for Metternich and Schwarzenberg: Nope, doesn’t sound like me at all.

Maria Theresa’s contemporaries already praised (...) her “manliness of soul,” her virilità d’anima. Some even called her a “Grand-Homme”; “in the attractive body of a queen” she was “fully a king, in the most glorious, all-encompassing sense of the word.” Later historians reprised the theme, describing her as a “man filled with insight and vigor.” That a masculine soul could reside in a female body had long been a commonplace, albeit one used less to elevate women than to cast shame on men. Praising a woman for her manly bravery or resolution, her masculine courage or spirit, served above all as an indirect criticism of men (…) When a woman is said to be the better man, this casts a devastating judgment on all her male peers. The key point is that calling an exceptional woman like Maria Theresa a “real man” consolidates the sexual hierarchy rather than calling it into question. Such praise assumes that masculinity is a compliment and that the male sex is and remains superior.

For the eighteenth century, a period when the dynastic principle still largely held sway throughout Europe, there was nothing especially unusual about a female head of state. While a woman on the throne was perceived even then as less desirable, she was not yet a contradiction; the spheres of the public and the private, politics and the family were not yet categorically distinct. Maria Theresa’s contemporaries already found it remarkable that a representative of the lesser sex could wield such power. But they did not regard her rule as entirely anomalous: she was “a woman, and a mother to her country, just as a prince can be a man and father to his country.” Her rule proved that “the greatest of all the arts, that of governing kingdoms, is not beyond the soul of a lady.” What was extraordinary, in the eighteenth-century context, was less the fact that a woman held the scepter of power than that a monarch, whether male or female, took the task of government so seriously. Princes came in many forms—patrons of the arts, skirt-chasers, war heroes, family fathers, scholars, philosophers—and each prince could shape his everyday life as he saw fit. Very few approached the task of rule with the single-minded dedication of a Maria Theresa. She met the criteria of a conscientious ruler to a remarkable degree, far more than most other sovereigns of the time.

Stollberg-Rilinger, Barbara (2020). Maria Theresa: The Habsburg Empress in her Time (translation by Robert Savage)

Always so interesting to me when I come across a historical figure who was noted to be constantly "in poor health" or "of a weak constitution" or some other shorthand for "they were always falling ill, even when others weren't and there was no obvious trigger for it." it really makes me wonder--how many of those people had what we'd today consider a chronic illness, and how many of them were just suffering from subpar sanitation in the past? how many of them had what could reasonably be considered a disability as opposed to just living in a time without modern medicine, and the people around them just couldn't diagnose them because the diagnosis didn't exist yet? this is something that I think about constantly btw

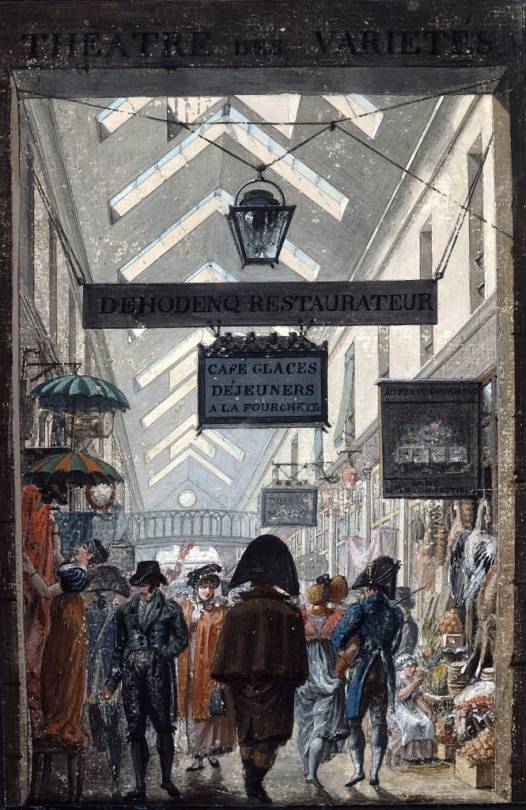

The Shopping Arcade des Panoramas in Paris, 1807 by Philibert Louis Debucourt