An inconvenience to society||she/they||art||I have no idea what im doing and I probably never will

74 posts

...having Been Thinking About Sir Gawain Again Recently And Remembering How Much I Like Talking About

...having been thinking about sir gawain again recently and remembering how much i like talking about it, have an essay i wrote about the avoidance of violence in the text for my History of English Literature class.

is it great? no lmao, i had a page count to hit. there's a lot of fluff. am i proud of it though? hell yes i am.

(quote numbers are line numbers in the Simon Armitage translation)

Unimportant Encounters—The Avoidance of Violence in Sir Gawain

Unlike an epic poem such as Beowulf, which places focus on heroic victories in combat, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, a romance poem, focuses on inter- and intrapersonal conflicts that are nonviolent in nature. In fact, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight tends to dance around violence in general, at least where Gawain is involved. In Fitt 2, the poet skips over Gawain’s encounters with various beasts, focusing instead on his encounters with people. This is because Gawain’s journey is not one of triumph in combat—rather, it is one of introspection and navigating expectations: both his and others’. The Sir Gawain poet demonstrates what the story is not by intentionally leaving out violence involving Gawain, and then emphasises it further by drawing attention to this lack: The poet references the skipped-over encounters with monsters in meta, Gawain’s interactions with the Green Knight subvert expectations, and Gawain is notably absent from the violence of the hunting trips. The poet also emphasises what the story is by intentionally focusing on the person-to-person interactions and conflicts of expectation that Gawain faces, and allowing these conflicts to dominate the story, both in terms of significance and line count.

After receiving the Green Knight’s challenge, Gawain “stayed [in King Arthur’s court] until All Saint’s Day [the first of November]” (line 536). In lines 691–739, the Sir Gawain poet tells us of the trials that Gawain undertook on his two-month journey. Compared to the seventy-four lines spent describing Gawain getting dressed before his trip, the poet relegates this entire section of Gawain’s adventure to just forty-nine lines. Further, the poet tells us that he battles many enemies “so foul or fierce he is bound to use force” (717). He mentions fights with serpents, wolves, wodwos, bulls, bears, boars, and giants, telling us that Gawain’s travels are “so momentous … [that] to tell just a tenth would be a tall order” (718–719). This description of victories almost echoes the boasts of an epic hero like Beowulf, telling of the myriad sea serpents he defeated, but unlike the Beowulf poet, who allows this bragging to take up physical space within the text, the Sir Gawain poet keeps this entire section to only about eleven lines. The poet minimises the space on the page that these encounters occupy, uses the format of a long, run-on list to add a rushed feeling to the section, and even references in meta that these stories are not important. They speak directly to the reader, telling them that it would be a “tall order” to describe these conflicts in detail, drawing their attention to the absence of such descriptions, and simultaneously implying that out of all the happenings that occur in the story of Gawain, this—this two-month journey filled with battles against numerous deadly foes—is the least important, the first to be cut.

The Sir Gawain poet also minimises the relevance and impact of violence by subverting expectations in Gawain’s encounters with the Green Knight. When the Green Knight first arrives in King Arthur’s hall, he is framed as imposing, frightening, powerful: the poet goes out of their way to describe the harm his ax is capable of doing; he speaks first in a bellow, demanding to see the leader of the hall; the guests of the hall watch him with dread, fearing that something terrible will come to pass—and yet, “expect no malice,” the Green Knight tells them (266). King Arthur even outright offers a fair fight, but the Green Knight turns him down, proclaiming “I’m spoiling for no scrap, I swear” (279). Further, even when he admits the violence he does want—a blow for a blow, a beheading for a beheading—the result is not as brutal as expected. The Green Knight, though bleeding, is not really harmed by the blow Gawain delivers to him, and simply rides off, severed head in hand, still very much alive. Then again, when Gawain goes to receive his beheading in turn, the poet builds expectations for violence. Gawain believes that he “might well lose [his] life” (2210), he describes the Green Chapel as “intending to destroy [him]” (2194), and he compares the sound of the ax sharpening to “the scream of a scythe”—a tool with famous associations to death (2202). Again, though, despite this, the beheading is underwhelming. The Green Knight does not kill Gawain—instead, he misses twice with his ax on purpose, and on the final swing his blow is intentionally “far from being fatal / … just skimming the skin” (2312). When Gawain lifts his own weapon, certain that the Green Knight will strike again to finish him off, the Green Knight chides him, telling him that with that one strike, he should “consider [him]self well paid” (2341), indicating that the Green Knight has no intention of further harm. With these subverted encounters, the Sir Gawain poet tells the reader that violence is not the point here, reinforcing the message implied in skipping over Gawain’s earlier encounters with monsters.

The poet provides yet another subversion away from violence in the hunting and bedroom scene parallels. The hunting scenes are not afraid to be violent, spending dozens of lines describing the methods by which the slaughtered creatures are processed. They use evocative, violent phrases—almost lustful in places—such as “severed with sharp knives”, “riving open the front”, “hoisted high and hacked away”, “slit the fleshy flaps”, “cleave”, and “break it down its back” (1337–1352). Myriad wildlife is slaughtered in these scenes, and in the boar hunt several of Lord Bertilak’s hounds are slaughtered by the boar’s “back-snapping bite” (1564), and even some of his men are wounded and killed. This stands in stark contrast to the bedroom scenes featuring Gawain. Besides his notable absence from the hunting scenes, his scenes in the bedroom are almost opposite to the hunting scenes. While Lord Bertilak and his men are using physical strength to enact violence, Gawain turns down Lady Bertilak’s advances in as polite a way as possible. He responds “merrily”, calls her his “gracious lady”, and asks her to “please pardon [him]” and allow him to “rise / … and pull on [his] clothes” (1213–1220). He is not tempted by lust, and the poet’s descriptions of these scenes are far from the evocative lustfulness used in the hunting scenes. Yet again, the poet is emphasising that violence does not play a role in Gawain’s journey.

Rather, Gawain navigates through social quandaries of duty using politeness and chivalry. The central plot is his obligation to meet the Green Knight and to honor the deal they made, despite it likely spelling his death. The deal itself was only made because of Gawain’s sense of duty to King Arthur—he acknowledges that the deal is “a foolish affair” (358), but volunteers himself so that Arthur will not have the obligation to participate. Additionally, Gawain takes on the deal with Lord Bertilak, and must carefully handle the advances of the Lady. The poet frames this struggle as a sort of battle in itself: Gawain “fence[s] and deflect[s] / all the loving phrases” of Lady Bertilak. When Gawain does eventually reach the Green Knight, it is revealed that these trials were a test of his character, and for passing, he escapes his fate of death. The Sir Gawain poet makes it very clear that the focus is on Gawain’s navigation of these competing loyalties; Gawain’s success in handling his clashing obligations allows him to avoid the violence of the Green Knight and return home alive. The poet also allows interpersonal conflict to dominate in line count—just as Beowulf spends most of the physical space in the text on combat (among other central themes), Gawain’s struggles with duty take up a significant portion of the text.

By allowing interpersonal social conflicts to dominate the space and significance of the text and by subverting expectations of violence and separating Gawain from the instances of violence that do occur, the Sir Gawain poet emphasises that the focus is on Gawain’s navigation of complex social situations and conflicting duties. The poet also intentionally minimizes the presence of violence. This avoidance of violence permeates the text and can be seen in the poet’s decision to skip over Gawain’s encounters with monsters, in the subverted expectations for the encounters with the Green Knight, and in Gawain’s absence from the more violent and lustful hunting scenes, as well as the absence of that same violence and lust from the bedroom scenes, making it clear that violence is not a central aspect of Gawain’s journey.

end note:

something i think i failed to make clear in the essay is why the incredible violence of the hunting scenes actually supports the idea that sir gawain's journey has nothing to do with violence. the biggest thing is sir gawain's LACK OF PRESENCE on the hunts. he does not, as an epic hero might, go along on the hunt and show off his physical prowess. rather, he stays home with the women and talks. an environment designed for violence is not one where he belongs.

-

baetrixx reblogged this · 9 months ago

baetrixx reblogged this · 9 months ago -

patches-of-mist liked this · 1 year ago

patches-of-mist liked this · 1 year ago -

garlic-flower liked this · 1 year ago

garlic-flower liked this · 1 year ago -

aykady liked this · 1 year ago

aykady liked this · 1 year ago -

bookshopwitch liked this · 1 year ago

bookshopwitch liked this · 1 year ago -

spectacled-studies liked this · 1 year ago

spectacled-studies liked this · 1 year ago -

jules-leigh liked this · 1 year ago

jules-leigh liked this · 1 year ago -

studywithvictory liked this · 1 year ago

studywithvictory liked this · 1 year ago -

theflowerbookworm liked this · 1 year ago

theflowerbookworm liked this · 1 year ago -

sourest-little-patch-of-them-all reblogged this · 1 year ago

sourest-little-patch-of-them-all reblogged this · 1 year ago -

sourest-little-patch-of-them-all liked this · 1 year ago

sourest-little-patch-of-them-all liked this · 1 year ago

More Posts from Sourest-little-patch-of-them-all

I cleaned my rat beanie baby today and when I took him out of the dryer and he was really warm

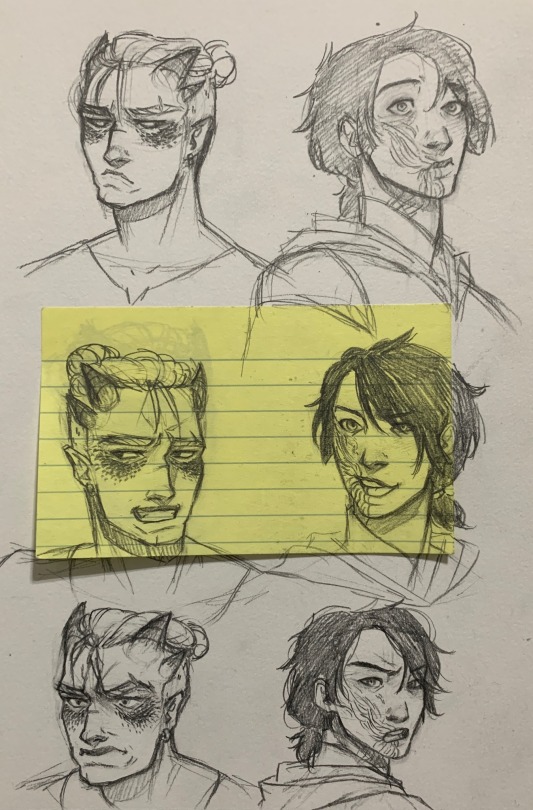

i got a little sketchbook so know i can draw studies and things wherever i go :D

I've been seeing a lot of shadow wizard money gangs and I just wanted to turn my persona into a wizard