Literary Analysis - Tumblr Posts

Jesus Never Existed - Kenneth Humphreys

The Gospels: History or Fiction? "The question concerning Jesus: do you want to know the real story, or just the...

― Eli Of Kittim, The Little Book of Revelation: The First Coming of Jesus at the End of Days

After much research, author Kittim has uncovered biblical information that changes everything we thought we knew about Jesus. His groundbreaking work will change the way you view the Bible! http://www.amazon.com/Little-Book-Revelation-First-Coming/dp/1479747068/ref=sr_1_1_title_0_main/182-1801190-2345619?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1402775551&sr=1-1

Scholarly Debate: Did Jesus Rise From The Dead? - Bart Ehrman Vs William Lane Craig "Although I believe in Jesus, I hold to Ehrman's view because Craig relies on dubious evidence." —― Eli Of Kittim, author of The Little Book of Revelation: The First Coming of Jesus at the End of Days

https://youtu.be/5-9-vWtTcU8

Scholarly Debate: Shabir Ally Vs William Lane Craig Did Jesus Rise from the Dead?

“In my view, the gospels are true, not historically, but theologically, or, as I would argue, prophetically! What we have is, the Messiah’s history written in advance in story form.“ ― Eli of Kittim, author of The Little Book of Revelation: The First Coming of Jesus at the End of Days

Jesus is a Gentile: The Evidence from the Gospels

By Award-Winning Author Eli of Kittim

In the New Testament, there are various ways in which Jesus is portrayed as a non-Jew. One of those depictions can be found in the Gospel of Matthew, which tells us right up front that Jesus does not come from the Kingdom of Judah (from the Jews) but rather from the region of Galilee (from the Gentiles; cf. Luke 1:26):

“Galilee of the Gentiles– THE PEOPLE WHO WERE SITTING IN DARKNESS SAW A GREAT LIGHT, AND THOSE WHO WERE SITTING IN THE LAND AND SHADOW OF DEATH, UPON THEM A LIGHT DAWNED.” (Matthew 4:15-16).

The Biblical scholar G.A. Williamson (translator of Eusebius’ The History of the Church: From Christ to Constantine) states that Jews formed only a minute portion of the Galilean population, and they were seldom seen in the province. Williamson also says that “the region was entirely Hellenistic in Sympathy.” He goes on to say that all of these facts are well-known to Christian scholars, yet they insist that “Christ was a Jew”.

According to 1 Kings chapter 9, King Solomon rewarded a Phoenician ally (King Hiram I) with twenty cities in the region of Galilee. So ever since the 10th century BCE, the land of Galilee was settled by foreigners and pagans. Galilee was once part of the Northern Kingdom of Israel. This kingdom fell into obscurity not only because much of its population was deported after the Assyrian invasion of 722 BCE, but also due to eight centuries of acculturation. Accordingly, in New Testament times, it had become the land of the Greco-Roman world (i.e. the land of the Gentiles)! That’s why it was known as “Galilee of the nations” (Isaiah 9:1)! This conclusion is archaeologically supportable. Jonathan L. Reed—professor of New Testament and Christian Origins, and a leading authority on first-century Palestine archeology—writes, “In fact, not a single synagogue from the first century or earlier has been found in Galilee” (Crossan, John Dominic, and Jonathan L. Reed. “Excavating Jesus.” San Francisco: HarperCollins, 2001, p. 25). Since then, only a few synagogues have been excavated in Galilee, with some possibly having been built after the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 CE, discoveries which in and of themselves hardly prove the existence of large Jewish communities in Galilee during the first half of the first century CE. Conversely, all but two tribes remained in the southern kingdom of Judah—-namely, the tribes of Judah and Benjamin (Ezra 1:5)—-which alone, strictly speaking, represent the term “Jews.” The term “Jew” (an abbreviation of the term “Judah”) was a geographical term which referred to those who came from the kingdom of Judah. In the New Testament story, however, Jesus is not called Jesus-of-Judah but rather “Jesus of Galilee” (Matthew 26:69)! As we will see, this is an extremely important piece of information!

Throughout the gospels, Christ is constantly at odds with the Jews, and even with Judaism itself—whether it be the Law of Moses, Jewish messianic prophecies, Jewish tradition, custom, culture, beliefs, and the like—that it is not difficult to see that he is not one of them. For example, the under mentioned verse exemplifies that Jesus was certainly not a Jew who studied under rabbis, as tradition holds. In the gospel story, he urges the disciples to completely disassociate themselves from the teachings of the Jews:

“Beware of the leaven of the Pharisees and Sadducees.“ (Matthew 16:11).

The Jews were of the opinion that the Messiah would come from Bethlehem, and from the Jews, as we continue to believe today. But they were in for a shock and were quite horrified to learn this was not the case. That’s the reason why John inserts this profound exclamation that comes from one of his characters:

“Nazareth!” exclaimed Nathanael. “Can anything good come from Nazareth?” (John 1:46).

The rift between Jesus and the Jews is once again evoked when Christ forbids the disciples from being called “Rabbi,” the traditional title of a Jewish scholar or teacher, especially one who studies or teaches Jewish law. Instead, he commands them to call him “teacher” (didaskalos)—a Hellenistic title—and not “rabbi”:

“Don’t let anyone call you ‘Rabbi,’ for you have only one teacher.” (Matthew 23:8).

What is worthy of notice is the fact that the gospels often do not present Jesus as a Jew, but rather as a Galilean—(“Jesus of Galilee” Matthew 26:69)—and a Samaritan (John 8:48) at that. In other words, Jesus is portrayed as a Gentile.

In his exhaustive book, “The Birth of the Messiah,” scholar Raymond E. Brown points out that biblical genealogies are important because the ancestors of a family line exemplify character traits or attributes that foreshadow something characteristic or stereotypical about a later figure. A genealogy, after all, is meant to show that someone has the right family credentials and is descended from a unique lineage. Yet, Raymond Brown is not exactly sure why four *foreign women* are mentioned in Matthew’s genealogy, and what their significance is in Matthew’s portrayal of Jesus. The answer is obvious. The 4 *foreign ancestors* of Christ exemplify that he, too, is a foreigner! Moreover, Professor Bart Ehrman asserts that both Matthew and Luke are recording the genealogy of Jesus through Joseph. Accordingly, the epiphany in the gospels that Jesus is not really Joseph’s son drives home the notion that his genealogy is not derived from the Jews (see the analogy between Jesus and Melchizedek in Heb. 7.2-6 in which the former is likened to the latter, “who does not belong to their [Jewish] ancestry,” implying that “the Son of God” is therefore not descended from the Jews either). This allusion becomes evident in another passage in which Jesus refutes the notion that he is the son or the descendent of David (the King of the Jews):

“Now while the Pharisees were gathered together, Jesus asked them a question: What do you think about the Messiah? Whose son is he?” They replied, “He is the son of David.” Jesus responded, “Then why does David, speaking under the inspiration of the Spirit, call the Messiah ‘my Lord’? For David said, The LORD said to my Lord, Sit in the place of honor at my right hand until I humble your enemies beneath your feet.’ Since David called the Messiah ‘my Lord,’ how can the Messiah be his son?” No one could answer him. And after that, no one dared to ask him any more questions.” (Matthew 22:41-46).

John’s gospel, in particular, shows that Christ’s teaching is not derived from the Jews, and that his origin or identity even defies the biblical expectations of a Jewish Messiah. For instance, Christ breaks the Law (John 5:16), and consequently the Jews want to kill him. That is why Jesus completely dissociates himself from the Jews by teaching and performing miracles exclusively in Galilee of the Gentiles (John 7:1). In fact, through the dialogues, the gospel suggests the unthinkable. Remember that there are no unnecessary words in the gospels. Every word is important. So, why does the gospel repeatedly emphasize the conflict between Jewish messianic expectations and the fact that Jesus does not meet them? Not only that, but John tells us explicitly that Jesus will not be found among the Jews, but among the Greeks! Jesus tells the Jews,

“’You will search for me but not find me. And you cannot go where I am going.’ The Jews said to one another, ‘Where does this man intend to go that we will not find him? Does he intend to go to the Dispersion among the Greeks and teach the Greeks?’” (John 7:34-35).

This dilemma between a Jewish and a Gentile Messiah is ever-present in John’s gospel. Jesus does not appear to come from the Jews and thus seems to defy scriptural expectations:

“Others said, ‘He is the Messiah.’ Still others asked, ‘How can the Messiah come from Galilee?’ ‘For the Scriptures clearly state that the Messiah will be born of the royal line of David [from Jews], in Bethlehem, the village where King David was born.’ So the crowd was divided about him. Some even wanted him arrested, but no one laid a hand on him.” (John 7:41-44).

In the following verse, we are told that none of the rabbis of Judaism can accept Jesus’ teaching—for his teaching is definitely not Judaic and even appears to contradict scripture. The Jews further imply that Christ’s followers are Gentiles, for they clearly do not know the Law of Moses:

“’No one of the rulers or Pharisees has believed in Him, has he?’ ‘But this crowd which does not know the Law is accursed.” (John 7:48-49).

A few verses later, the Jews go on to say,

“Search the Scriptures and see for yourself–no prophet ever comes from Galilee!“ (John 7:52).

These inclusions in the text by the gospel writer John clearly give us a different perspective on Jesus the Messiah, as far as his origin or identity is concerned. If he were Jewish, the Jews would certainly have accepted him, celebrated him, and honored him as one of their own. We therefore come to realize why they dislike him so intensely and why he offends them throughout the gospel stories. Because he is a Gentile!

Similarly, in Luke 4:23-29 the Jews became enraged because Jesus said that Elijah was sent to the Gentiles, not to the Jews–implying that he himself turns from Jews to Gentiles. John Dominic Crossan writes, “In that case, Jesus’ turn from Jews to Gentiles is cause rather than effect of eventual rejection and lethal attack” (Excavating Jesus, p. 28).

This theme reminds us of the stories of Joseph and Moses (two messianic stand-ins who are also rejected by their “brothers,” the Jews)—and who are portrayed in the Bible as living and reigning in Egypt (the land of the Gentiles). By analogy, Matthew has Christ supposedly going to Egypt in order to make this connection and to show us that he’s the new Moses:

“OUT OF EGYPT DID I CALL MY SON.” (Matthew 2:15).

Thus, all these messianic figures, including Jesus, are essentially depicted as Gentiles! That’s precisely why Cyrus, a gentile, is called God’s Messiah in Isaiah 45.1! Not to mention that King David himself was not a Jew; he was a Moabite! Similarly, in Isaiah 46:11, God says: I have chosen “a man for My purpose from a far-off land” (cf. Matt. 28:18; 1 Cor. 15:24-25). This motif is also seen in Matthew 21:4-5 and John 12:14-15, which portray Jesus as a Gentile in fulfillment of Zechariah’s (9:9) prophecy. That’s because in Biblical nomenclature, the ox represents Israel, while the ass represents the Gentiles. Thus, the symbolism of the Messiah entering the holy city and riding on a donkey represents Jesus' Gentile ancestry! Paul’s emphasis of this point—which constitutes “the mystery that has been kept hidden for ages and generations, but is now disclosed to the Lord’s people” (Colossians 1:26)—about Christ’s identity bears repeating:

“Therefore I will praise you among the Gentiles; I will sing hymns to your name.” Again, it says, “Rejoice, O Gentiles, with his people.” And again, “Praise the Lord, all you Gentiles, and sing praises to him, all you peoples.” And again, Isaiah says, “The Root of Jesse will spring up, one who will arise to rule over the nations; the Gentiles will hope in him.” (Romans 15:9-12).

The gospel of John makes clear that Jesus’ teaching is a serious threat to the Jews because it completely nullifies Judaism, as well as the Jewish temple—so much so that the Sanhedrin fears that this Gentile (non-Jewish) teaching will cause the entire nation to fall:

“So the chief priests and the Pharisees gathered the council and said, “What are we to do? For this man performs many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and the Romans will come and take away both our place and our nation.” (John 11:47-48).

Of further interest is the dichotomy between Jesus and his Jewish audience, one in which there is a clear “I versus you” mentality running throughout the text. Jesus separates himself from the Jews by addressing them as if they were not his own people—“Your” nation, “Your” ancestors, “Your” fathers, “Your” prophets, “Your” Law, etc.—making it abundantly clear that there is a clear distinction between Jesus and the Jews:

1) “Jesus answered them, ‘Is it not written in YOUR Law…?’” (John 10:34, emphasis added).

2) “YOUR own law says that…” (John 8:17, emphasis added)

3) “I know YOU are descendants of Abraham, but you are trying to kill Me because My word is not welcome among you.” (John 8:37, emphasis added).

4) “YOU are doing the works of your own father.“ (John 8:41, emphasis added).

Also notice that while arguing with the Jews—who seek to kill him because they claim he is a Gentile—Jesus does not refute that he is a Gentile, he only refutes the idea that he has a demon:

“The Jews answered him, ‘Are we not right in saying that you are a Samaritan [Gentile] and have a demon?’ Jesus answered, ‘I do not have a demon, but I honor my Father, and you dishonor me.’” (John 8:48-49).

So, in John’s gospel, Jesus is called a ‘Samaritan’—a Greek—and he does not appear to deny it. Further evidence that Jesus is not a Jew can be ascertained from the fact that, in the gospel story, he is not tried in a Jewish court but rather in a Roman—one which was reserved exclusively for Gentiles; that is, for Roman and Greek citizens! Neither was he killed by stoning, which was the traditional custom for killing a Jew. Moreover, some church fathers (e.g. Clement of Alexandria) have claimed that the name “Ιησους” (i.e. Jesus) has a Greek origin, not a Hebrew one. All these clues purvey insights and teachings about a Gentile Messiah who does not conform to our rather facile biblical expectations. In fact, both Jesus and all of his disciples come from Galilee. Ironically, only one of his disciples is a Jew who comes from Judah: the one who betrays him!

Furthermore, the New Testament could not have been written by devout Jews because devout Jews would not have written in Greek. It was forbidden for them to do so. Nor could they have written such articulate, refined Greek. From the earliest times, devout Jews could only read Hebrew. During the Babylonian exile, the Jews wrote in Aramaic. During Hellenistic times, even though the official language was Greek, devout Jews continued to write in Aramaic and could not have written in Greek for fear of being dejected from their sect or congregation! Besides, ever since the overthrow of the Syrian-Greek Empire in the land of Israel, the Jews hated anything to do with the Greeks.

So, who else is left who could have written the New Testament in Greek? Answer: Greeks! And there are more epistles written to Greeks than to any other race. In fact, most of the New Testament books were written in Greece: Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, Titus, the book of Revelation, and possibly others as well! None of the books of the New Testament were ever written in Palestine. Not even the Letter of James. According to scholars, the cultivated Greek language of the Epistle of James could not have possibly been written by a Jerusalem Jew!

It is also important to note that when the NT authors quote from the OT, they often quote from the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, and not from the original Hebrew scriptures per se. This may indicate that the NT authors were not familiar with the Hebrew language. For example, when they quote Jeremiah or refer to Joshua (Acts 7:45; Heb. 4:8) in the NT, they use the Septuagint (the Greek text) as their source (scholarly consensus). This lends plausibility to the argument that the NT authors were not Hebrews but Greeks! And scholars now tell us that these NT authors were writing from different parts of the world, not from Palestine.

And why didn’t the New Testament writers finish God’s story in Hebrew? What better way to persuade Jews that Jesus is the messianic fulfillment of Jewish Scripture than to write it in the Hebrew language, which Jews could both read and understand? But they didn’t! The reason for this is Jesus. Apparently, he is not Jewish; he is Greek! So, the story must be written in Greek to reflect its main character, the God man, Jesus the Christ. Furthermore, if he were Jewish, he would have said I am the Aleph and the Tav. Instead, he uses Greek letters to define the divine “I AM”:

“I am the Alpha and the Omega,” says the Lord God.” (Revelation 1:8).

The following verse shows that we are on the right track. John the Revelator is not in Greece by accident. He is there BECAUSE (for the reason that) it has everything to do with the SPECIFIC ACCOUNT of Jesus, which is revealed to him by the word of God:

“I, John … was on the island called Patmos [in Greece] BECAUSE of the word of God and the testimony of Jesus.” (Revelation 1:9, emphasis added).

If we sum up our findings, we could say with confidence that the mystery of Jesus’ non-Jewish identity is revealed even in the gospels. And the gospel mystery of Christ’s identity is supported by no less an authority than Paul:

“This message was kept secret for centuries and generations past, but now it has been revealed to God’s people.” (Colossians 1:26).

In his in-depth-Bible-study video called “Breaking the Sound of Silence,” distinguished scholar Brant Pitre agrees that “the mystery which was kept secret for long ages but is now disclosed and through the prophetic writings is made known to all nations” (Rom. 16.25b-26a) is exclusively referring to a *revelation* of Jesus’ *identity* that was previously unknown! That’s why “the mystery which was kept secret for long ages” needed to be revealed. Because we could not have possibly known this truth from any available sources (biblical or otherwise) except by way of divine revelation! There is much more proof in the Bible that Jesus is Greek (and not Jewish). But this evidence cannot be reproduced here, given the limited scope of this article.

.

The Little Book

http://www.goodreads.com/book/show/19737698-the-little-book-of-revelation

Realized Eschatology versus Future Eschatology

By Author Eli of Kittim

Realized eschatology is a term in Christian theology used to describe the belief that the end times (or latter days) have already happened during the ministry of Jesus. According to this position, all end-time events have already been “realized” (i.e., fulfilled ), including the resurrection of the dead, and the second coming of Jesus.

This view is the culmination of poor methodological considerations, misapplication of proper exegetical methods (i.e. literary context /detailed exegesis), and a confusion of terms and context. The under-mentioned examples typify this confusion:

Example A) “Dear children, this is the last hour; and as you have heard that the antichrist is coming, even now many antichrists have come. This is how we know it is the last hour” (1 John 2:18).

Example B) “In the past God spoke to our ancestors through the prophets at many times and in various ways, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son…” (Hebrews 1:1-2).

Here, without a proper understanding of context, we are led to believe that John is referring to the “last days” as occurring in or around the 1st century CE. These types of verses have misled many to follow Preterism, a doctrine which holds that biblical prophecies represent incidents that have already been fulfilled at the close of the first century. Unfortunately, the same type of misappropriation of scripture has given birth to “realized eschatology.”

Notice that in Example A, John states that “it is the last hour.” The context implies that there are two possibilities within which this phrase can make scriptural sense. Either John is literally referring to the 1st century as being the last or final hour of mankind (which would include the coming of the Antichrist, since John mentions him), or the overall context of this and other texts is, strictly speaking, an eschatological one in which all these events take place in the future, and not during John’s lifetime.

As I have shown in earlier works, scriptural tenses that are set in the past, present and future do not necessarily correspond to past, present or future history respectively. What is more, logic tells us that “the final point of time” represents the end of the world. Yet there are future events that are clearly described in the past tense. For example, “He [Christ] … was revealed at the final point of time” (1 Pet. 1:20, NJB, emphasis added). In a passage that deals exclusively with the great tribulation of the end times, we find another future event that is described in the past tense; it reads: “From the tribe of Judah, twelve thousand had been sealed” (Rev. 7:5, emphasis added). Isaiah 53 is a perfect example because we can demonstrate that Isaiah was composing a prophecy, at the time he penned this text, which was saturated with past tenses.

In Example B, we face a similar dilemma. The author of Hebrews combines the idiomatic phrase “last days” with the present tense “these,” which implies several things:

1) The phrase “in these last days” gives us the impression that the “last days” may have started or occurred during the author’s lifetime.

2) It implies that Jesus not only appeared, but he appeared specifically “in these last days.”

3) The phrase “in these last days” might simply be an allusion to the days just mentioned. It’s like saying, concerning the days in question, or with regard to the days that we are describing, rather than a reference to the present time.

So, at first sight, there seems to be some basis (biblical support) for a realized-eschatology interpretation. However, upon further scrutiny, we find many outright logical fallacies (a logical fallacy is, roughly speaking, an error of reasoning) that cannot possibly be true. For example, how can the last days of the world occur in the 1st century CE if nineteen plus centuries have since come and gone? It would be a contradiction in terms!

Moreover, these positions flatly contradict not only the broad scriptural context of the term “last days” and its cognates (i.e., “the time of the end” Dan. 12:4), but also certain definite future events, such as the “great tribulation” (Matt. 24:21; cf. Daniel 12:1-2) and the coming of the “lawless one” (2 Thess. 2:3-4; cf. Rev. 13), which clearly have yet to occur. Therefore, the so-called “realized” eschatological interpretations involve logical fallacies, blatant misappropriation of future events, methodological errors, misapplication of proper exegetical methods, and misinterpretation of tenses with regard to proper eschatological context.

Contradiction notwithstanding, many have endorsed these false teachings. Daniel 12 and Matthew 24 are two examples that demonstrate beyond a shadow of a doubt that “the time of the end” is radically different than what these interpreters make it out to be, namely, a first-century occurrence. These views (regarding the last days as eschatological events that occurred in the 1st century CE) display, for lack of a better term, an eccentric doctrine. They are patently ridiculous!

The same holds true in the gospel of John. Jesus says:

“Truly, Truly, I say to you, the hour is coming and now is, when the dead will hear the voice of the son of God; and those who hear will live” (John 5:25).

The phrase “and now is” implies that this particular time period is happening now. However, notice a clear distinction between the hour that is here and “the hour that is coming” when the dead will rise again (in the under mentioned verse). These two time periods are clearly not identical because the events to which the latter prophecy points have yet to happen:

“Do not marvel at this; for the hour is coming in which all who are in their graves will hear his voice, and come forth, … those who have done good, to the resurrection of life, and those who have done evil, to the resurrection of condemnation” (John 5:28-29).

The context of John 5:25 ff. is ultimately based on future history (i.e., history written in advance), but the author reinterprets it through a theology. On what basis am I making these claims? Since I concluded that “realized eschatology” is seemingly erroneous, we now have to consider its opposite, namely, the view that the last days are really referring to literal future events, and not to the time of Antiquity.

One illustration of this view is in the context in which Jesus’ earthly appearance is contemporaneous with Judgment Day. Jesus uses the present tense “now” to indicate that his manifestation on earth is for the purpose of Judgment, and the overthrow of Satan:

“Now is the time for judgment on this world; now the prince of this world will be driven out” (John 12:31).

Jesus’ use of the word “now,” in connection with the removal of Satan and Judgment, would indicate that his earthly appearance (as described in the gospels) is a reference to a future event, one that could not have possibly happened in Antiquity.

Another example shows that Christ’s generation (as described in the gospels) is the last generation on earth. During his eschatological discourse, Christ uses the words “this generation” to refer to his audience. He says,

“Truly I tell you, this generation will certainly not pass away until all these things have happened” (Matthew 24:34).

In the following verse, Jesus uses the words “some who are standing here” to signify his audience. Interestingly enough, Jesus implies that his audience (or generation) is the one related to the end times. The idea that Jesus’ audience (as described in the gospels) represents the last generation on earth that would see Jesus coming in the clouds is furnished in the gospel of Matthew:

“Truly I tell you, some who are standing here will not taste death before they see the Son of Man coming in his kingdom" (Matthew 16:28).

The notion that some of Jesus’ followers would not die before they saw him coming in glory cannot be attributed to the 1st century CE. It can only be ascribed to a future event, since Jesus has yet to come in his glory! These verses would strongly suggest that the account of Jesus (as described in the gospels) is really in the context of a future event rather than one that occurred in the 1st century of the Common Era.

In conclusion, scriptural tenses that are set in the past, present and future do not necessarily correspond to past, present or future history respectively. What is more, both scripture and logic tell us that “the final point of time” represents the end of the world, and therefore this “end time” period could not have possibly happened during the 1st century CE.

There are also gospel materials, which indicate not only that Jesus’ audience represents the last generation on earth, but that Jesus’ manifestation on earth signifies the immediate removal of Satan and the commencement of Judgment. Add to this material the original Greek texts—with multiple references to Jesus appearing “once at the consummation of the ages” (Heb. 9:26; cf. Luke 17:30; Heb. 1:1-2; 1 Pet. 1:5, 20; Rev. 12:1-5) or at the end of human history—and the eschatological context of the “last days” finally comes into view as a future reference!

Bart Ehrman’s “Did Jesus Exist?”: A Critical Review by Author Eli Kittim

——-

Unfortunately, my version does not have numbered pages, nevertheless the quotes are taken directly from his book, word for word!

——-

“Did Jesus Exist? The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth is a 2012 book by Bart D. Ehrman, a scholar of the New Testament. In the book, written to counter the idea that there was never such a person as Jesus of Nazareth at all, Ehrman sets out to demonstrate the historical evidence for Jesus' existence, and he aims to state why all experts in the area agree that ‘whatever else you may think about Jesus, he certainly did exist’ “ (Did Jesus Exist? [Ehrman book] -Wiki).

——-

1 Bart Ehrman is not only dead wrong but also disingenuous. He writes: “The idea that Jesus did not exist is a modern notion. It has no ancient precedents. It was made up in the eighteenth century. One might well call it a modern myth, the myth of the mythical Jesus.” That is completely bogus! It’s an idea that was held as early as the second century CE, and it was known as Docetism. This was the notion that Jesus did not have a physical body: that he did not come in the flesh!

——-

2 Ehrman’s defense of Jesus’ existence is based on presuppositions and circular thinking. He presupposes that certain literary characters are *obviously* historical figures who must have known Jesus. But this is arguing in a circle because he doesn’t prove their historical existence beyond the literary narrative. On the contrary, we have every reason to believe that these are fictional characters that are employed in works of *historical fiction* as, for example, when we are told that Paul the Pharisee is working for the High Priest of the Jerusalem Temple who’s a Sadducee, which seems like a total fabrication since Pharisees and Sadducees were bitter rivals.

——-

3 Moreover, the gospels were written in Greek, and most scholars assume that their sources were also in Greek. The writers are almost certainly non-Jews who are copying and quoting extensively from the Greek Old Testament, not the Jewish Bible. They obviously don’t seem to have a command of the Hebrew language, otherwise they would have written their gospels in Hebrew. And most of them, if not all of them, are writing from outside Palestine. By contrast, the presuppositions Ehrman is making do not square well with the available evidence. He’s arguing that Jesus was an Aramaic peasant from the backwaters of Galilee who had 12 Aramaic disciples who were also peasants. He also contends that the oral traditions or the first stories about Jesus began to circulate shortly after his death, and these oral traditions were, according to Ehrman, obviously in Aramaic.

——-

4 But here’s the question. If a real historical figure named Jesus existed in a particular geographical location, which has its own unique language and culture, how does the story about him suddenly get transformed and disseminated in an entirely different language within less than 20 years after his purported death?

——-

5 Furthermore, who are these sophisticated “Greeks” who own the rights to the story, as it were, and who pop out of nowhere, circulating the story as if it’s their own, and what is their particular relationship to this Aramaic community? Where did they come from? And what happened to the Aramaic community and their oral traditions? It suddenly disappeared? Given these inconsistencies, why should we even accept that there were Aramaic oral traditions? If the Aramaic community did not exist, neither did their Aramaic character! That’s the point.

——-

6 Besides, if Paul was a Hebrew of Hebrews who studied at the feet of Gamaliel, surely we would expect him to be steeped in the Hebrew language. Yet, even Paul is writing in sophisticated Greek and quoting extensively not from the Hebrew Bible (which we would expect) but from the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament. Now that doesn’t make any sense at all! All of a sudden, Paul’s literary identity becomes suspect. Since Paul’s community represents the earliest Christian community that we know of, and since his letters are the earliest known writings about Jesus, we can safely say that the earliest dissemination of the Jesus story comes not from Aramaic but from Greek sources!

——-

7 What is more, independent attestation does not necessarily prove the historicity of the story, only its popularity. For example, if Dan Brown writes a piercing novel that captures the popular imagination, just because other writers copy the story and begin to give it their own unique expression doesn’t mean that the story in and of itself is based on historical fact. The same principle should hold true with the New Testament gospels that were widely copied by noncanonical works, and which were not in themselves historically-reliable accounts to begin with.

——-

8 All other mentions, from the second to the fourth centuries, seem irrelevant not only because of their lack of proximity to the purported events (being based neither on eyewitnesses nor firsthand accounts), but also because of inaccurate information. For example, consider Eusebius’ criticism of Papias, who claimed that Matthew wrote in Hebrew (an assertion that has been dismissed by scholars). Or how about Papias’ so-called “sources of knowledge about Jesus” in which he mentions some of the latter’s important disciples in order to impress his audience (a claim that seems highly unlikely because the original apostles would not have been around by then). These tales, of course, play right into Eusebius’ playbook of creating fictional accounts that lead back to the so-called “original” apostles and to the alleged historical Jesus. However, we’re simply reading Papias through Eusebius’ lens. Let’s not forget that Eusebius himself had created so many fables and legends about the martyrs and apostles, and had been criticised as historically unreliable and biased, not to mention that he was too-far removed from the purported events, writing in the 4th century of the Common Era.

It’s unfortunate that Ehrman has to resort to such types of “evidence” to try to defend Jesus’ historicity. It would be quite gullible for any scholar to simply accept Eusebius’ account of Papias at face value.

According to the Jesus Seminar, which comprised a large group of approximately 50 critical biblical scholars, we don’t really know what Jesus said. Why would someone from one century later (like Papias) know what Jesus said? Then why doesn’t he also tell us what Jesus looked like? Or what language he spoke? Why didn’t the companions of the apostles not disclose this information to him?

——-

9 Then Ehrman quotes a devotional homily written by Ignatius of Antioch, which is probably inspired by the gospels and therefore has no historical value whatsoever, and concludes: “Ignatius, then, provides us yet with another independent witness to the life of Jesus.”

——-

10 Ehrman aims to prove the historical Jesus by referencing 1 Clement. But how does 1 Clement prove the historicity of Jesus? How can a letter from Rome, composed more than 60 years after Jesus’ purported death, demonstrate Jesus’ actual existence? Once again, we have a devotional piece based possibly on some type of “Scripture.” But in the absence of hard evidence and eyewitness testimony, 1 Clement is useless as evidence for the historical Jesus. Yet Ehrman writes:

“Here again we have an independent witness not just to the life of Jesus as a historical figure but to some of his teachings and deeds. Like all sources that mention Jesus from outside the New Testament, the author of 1 Clement had no doubt about his real existence and no reason to defend it.”

With all due respect, that’s a lame statement and there’s no excuse for a scholar of such caliber to be making these types of blunders.

——-

11 Ehrman then employs a speech from the Book of Acts:

“Men of Israel, hear these Words. Jesus the Nazarene, a man attested to you by God through miracles and wonders and signs that God did through him in your midst, just as you know, this one was handed over through the hand of the lawless by the appointed will and foreknowledge of God, and you nailed him up and killed him; but God raised him by loosing the birth pangs of death” (2:22–24).

Question: according to this passage, how was Jesus handed over to them for crucifixion? Answer: “by the appointed will and foreknowledge (προγνώσει) of God.” In other words, the passage seems to indicate that it’s a prophecy that hasn’t happened yet.

Besides, we don’t even know if these speeches in Acts are made-up stories or if they coincide with actual reality, especially since 2 Tim. 2.17-18 argues that the resurrection hasn’t happened yet. Similarly, 2 Thess. 2.1-3 argues that Jesus hasn’t come yet.

——-

12 Dr. Ehrman then quotes from 1 Peter:

“For you were called to this end, because Christ suffered for you, leaving an example for you that you might follow in his steps, who did not commit sin, nor was deceit found in his mouth, who when reviled did not revile in return, while suffering uttered no threat, but trusted the one who judges righteously, who bore our sins in his body on the tree, in order that dying to sin we might live to righteousness, for by his wounds we were healed” (2:21–24).

And yet if you read 1 Peter 1.20 in the original Greek there is absolutely no way that Jesus could have existed in Antiquity:

“He was marked out before the world was made, and was revealed at the final point of time” (NJB).

Similarly, 1 Jn 2.28 places the “revelation” of Christ in eschatological categories:

“And now, little children, abide in him, so that when he is revealed [φανερωθῇ] we may have confidence and not be put to shame before him at his coming.”

By the way, to be “revealed” means for the first time; it’s a first-time disclosure (for further details see my article: https://eli-kittim.tumblr.com/post/187927555567/why-does-the-new-testament-refer-to-christs

That’s why, according to Lk 17.30, the Son of Man has not yet been revealed:

“it will be like that on the day that the Son of Man is revealed.”

——-

13 Then Ehrman quotes 2 Peter:

“For not by following sophistic myths have we made known to you the power and presence of our Lord Jesus Christ, but we were eyewitnesses of the majesty of that one. For when we received honor and glory from God the Father and the voice was brought to him by the magnificent glory, ‘this is my beloved Son in whom I am well pleased,’ we heard this voice that was brought from heaven to him, for we were on the holy mountain” (1:16–18).

What Ehrman fails to tell you is that the following verse, 2 Pet. 1.19, indicates that these were not historical events but rather experiences of visions and auditions that pointed to a future-eschatological prophecy:

“So we have the prophetic message more fully confirmed.”

Then Ehrman goes on to say that “Even the book of Revelation, with all its bizarre imagery and fantastic apocalyptic views, understands that Jesus was a real historical figure. For this author he was one who ‘lived’ and who ‘died’ (1:18).” Yet Ehrman fails to mention that in the Book of Revelation Jesus is said to be born in the end-times, as a contemporary of the final empire on earth which is depicted as a seven-headed dragon with ten horns (Rev. 12.1-5). Moreover, the testimony to Jesus in the Book of Revelation is said to be prophetic, not historical! Compare Rev. 19.10d:

“For the testimony [to] Jesus is the spirit of prophecy” (NRSV).

——-

14 Ehrman then quotes from the Book of Hebrews:

“Jesus appeared in ‘these last days’ (1:2).”

But that is an incorrect interpretation. The Greek implies that Jesus’ appearance takes place ἐπ’ ἐσχάτου τῶν ἡμερῶν (in the last days), not in Antiquity.

More explicit and quite unambiguous is Hebrews 9.26b:

“he has appeared once for all at the end of the age to remove sin by the sacrifice of himself.”

Studies in Greek reveal that the phrase “at the end of the age” always refers to the future-eschatological time of the end (cf. Dan. 12.4 LXX; Mt. 13.39-40, 49; Mt. 24.3; Mt. 28.20). Once again, all these verses are indicating a prophecy, not a historical event from the past. In particular, Hebrews 9.26b explicitly states that Jesus will die for the redemption of sins “at the end of the age,” or “in the end of the world” (KJV)!

——-

15 At this point of the discussion, Dr. Ehrman sets out to demonstrate Paul’s testimony to Jesus:

“The reality is that, convenient or not, Paul speaks about Jesus, assumes that he really lived, that he was a Jewish teacher, and that he died by crucifixion. The following are the major things that Paul says about the life of Jesus. First, Paul indicates unequivocally that Jesus really was born, as a human, and that in his human existence he was a Jew. This he states in Galatians 4:4: “But when the fullness of time came, God sent his son, born from a woman, born under the law, that he might redeem those who were under the law….”

The problem is that Ehrman doesn’t understand Greek, nor is he a trained exegete, so he misses the point entirely!

In fact, according to Gal. 4.4 and Eph. 1.9-10, Jesus will be incarnated in “the fullness of time”, or at the end of the age! The Greek phrase τὸ πλήρωμα τοῦ χρόνου (the fullness of time) means when time reached its fullness or completion. And Eph. 1.9-10 clearly demonstrates that it refers to the end-times and the final consummation!

Then Ehrman goes on to talk about the brothers and sisters of the Lord in order to show that Jesus was a real historical person who was surrounded by siblings. However, this proves nothing, not only because these may simply be literary stories that meet the authors’ objectives but also because it can be shown that these are not actual biological blood-relatives of Jesus (see my article: https://eli-kittim.tumblr.com/post/611675702018883584/was-james-the-brother-of-jesus-given-that

——-

16 After this, Ehrman mentions the resurrection and tries to show that “after Jesus was raised on the third day, ‘he appeared to Cephas and then to the twelve’ (1 Corinthians 15:5).” But what Ehrman doesn’t tell you is that these were visions of a prophecy that would take place at the end of the age! In Acts 10.40-41 we are told that Jesus’ resurrection is only visible “to witnesses who were chosen beforehand by God” (προκεχειροτονημένοις; NASB). Nor does Ehrman tell you that Paul uses the word “eschaton,” which is a reference to the “last days,” as if he were talking about a prophecy. At any rate, Paul says ἔσχατον δὲ πάντων which could be translated “last then of all” or “at the end of all” “as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me” (1 Cor. 15:8). But the way Paul explains it, his use of the word καμοί (also to me) connotes “in the same way or manner,” which lends credence to the idea that Christ had appeared to him as he had to others: that is to say, by way of visions (cf. Gal. 1.15-16; Acts 9.3-5).

——-

17 Ehrman concludes:

“Finally, Paul is quite emphatic throughout his writings that Jesus was crucified. He never mentions Pontius Pilate or the Romans, but he may have had no need to do so.”

But again, as we will see, there are 2 things to consider, here. First, Paul is not referring to a historical event but to a tradition (to a prophecy) that was handed down to him and which he in turn delivered on to us (the readers/believers). Second, a close reading reveals that Christ didn’t die according to the historical record but rather “Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures.” This is a crucial point. Jesus did not die a historical death, according to past history; rather he died κατὰ τὰς γραφάς, according to the *prophetic writings* that were handed down to Paul:

“For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures” (1 Cor. 15.3-4).

And it is for this reason that Paul “never mentions Pontius Pilate or the Romans,” precisely because they’re irrelevant to the *prophetic writings*!

——-

18 Finally, it doesn’t really matter how many sayings of Jesus Paul (or anyone else) reiterates because they’re irrelevant in proving Jesus’ historicity. Why? Because Paul claims that his gospel is not of human origin: “I did not receive it from a human source, nor was I taught it, but I received it through a revelation of Jesus Christ” (Gal. 1.12). The point is that all these sayings of Jesus may have come by way of revelation and not from a historical Jesus!

——-

Conclusion

Ehrman should know better. There were quite a few early-Christian, Gnostic sects that held to a Docetic belief, namely that Jesus did not exist in physical form. This idea was certainly not invented in the 18th century.

——-

Ehrman also misinterprets certain clearly fictional characters as if they were historical figures, and therefore confuses historical fiction with biography (cf. Acts 9.1-2). Here’s a case in point. Besides the fact that the High priest of the Jerusalem Temple was a Sadducee, who wouldn’t be normally working with a Pharisee, he had absolutely no jurisdiction in Damascus. So what’s Paul doing there persecuting Christians? This is odd because the Christians were hardly a threat compared to the Romans at that point in time. So what’s Paul doing chasing them all the way to Syria? Nothing in the story seems historically accurate or probable. In fact, all the elements of this story spell *fiction,* not fact!

——-

And why are the earliest New Testament writings in Greek? That certainly would challenge the Aramaic hypothesis. How did the Aramaic oral tradition suddenly become a Greek tradition within less than 20 years after Jesus’ supposed death? That kind of thing just doesn’t happen over night. It’s inexplicable, to say the least.

——-

Moreover, who are these “Greeks” who took over the story from the earliest days? And what happened to the alleged Aramaic community? Did it suddenly vanish, leaving no traces behind? It might be akin to the Johannine community that never existed, according to Dr. Hugo Mendez. It sounds more like a conspiracy of sorts.

——-

And if Paul was a Hebrew of Hebrews who studied under Gamaliel, what is he doing quoting from the Greek Old Testament? Why are his epistles not in Aramaic or Hebrew? By the way, these are the earliest writings on Christianity that we have. They’re written roughly two decades or less after Christ’s alleged death. Which Aramaic sources are they based on? And if so, why the need to quote the Septuagint? Or to record his letters in Greek? The Aramaic hypothesis doesn’t hold up.

——-

Finally, the quite obvious interpolations in the works of Josephus and Tacitus are conceded by many Biblical scholars. Many works were actually collaborations rather than corroborations. For example, Pliny the Younger corresponded with Tacitus, demonstrating that their accounts cannot be deemed as independent attestations. And the various non-canonical offshoots can not be used as evidence to prove historicity but rather how *popular* a story was. The various legendary elements were seemingly fused with historical figures and geographical locations to give the writings a sense of verisimilitude, as any good fictional story should do. Dan Brown is a master novelist who always adds such historical elements to his stories. Similarly, it would be stretching credulity to take these clearly fictional and non-canonical stories——whose authorship, production, and dissemination is itself dubious——and turn them into historiographical facts.

——-

And I hardly fit the mould of those mythicists to whom Ehrman’s criticism is directed:

“Ehrman says that they do not define what they mean by ‘myth’ and maintains they are really motivated by a desire to denounce religion rather than examine historical evidence” (Did Jesus Exist? [Ehrman book] - Wiki).

First, I am not a mythicist; I’m an ahistoricist. That is to say, I do not believe that the story of Jesus is a *myth.* I believe it is a *prophecy* (cf. Heb. 9.26b; 1 Pet. 1.20; Rev. 19.10d)!

In other words, I don’t believe that the story of Jesus is a “mythological” motif, based on preexisting pagan myths, or that he never existed and never will. Rather, I believe that the New Testament evidence supports the notion that the Jesus-story is based on “revelations” (Gal. 1.11-12) and “prophetic writings” (see Rom. 16.25-26; 2 Pet. 1.19-21; Rev. 22.18-19).

Second, I am not “really motivated by a desire to denounce religion rather than examine historical evidence.” On the contrary, I have a high Christology and hold to a high view of Scripture. So, I don’t have an axe to grind. I actually believe in Christ, and I also believe that the Bible is the word of God. I’m just able to look at all the facts dispassionately, without any biases or presuppositions, and follow the facts wherever they may lead.

——-

All in all, I find Ehrman’s defence rather weak, and his arguments quite ineffective. In fact, the lack of archeological and interdisciplinary evidence for the existence of Jesus, coupled with the lack of eyewitness reports and firsthand accounts, seems to point in the opposite direction than Ehrman would have us believe. Not to mention that he seems to be unfamiliar with Koine Greek, ultimately mistranslating and misinterpreting the text!

——-

I’ll close with the words of a world-class Bible scholar and highly respected textual critic. Kurt Aland——who’s a world-renowned textual scholar, having founded and directed the Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Münster, Germany, and who was one of the chief editors of the Nestle-Aland - Novum Testamentum Graece (the critical edition of the New Testament)——went so far as to question the historicity of Jesus:

“If the . . . epistles were really written by the apostles whose names they bear, and by people who were closest to Jesus . . . then the real question arises . . . was there really a Jesus?” “Can Jesus really have lived if the writings of his closest companions are filled with so little of his reality . . . so little in them of the reality of the historical Jesus . . .” “When we observe this——assuming that the writings about which we are speaking really come from their alleged authors——it almost then appears as if Jesus were a mere PHANTOM. . .“

(“A History of Christianity,” Vol 1, by Kurt Aland, p. 106 - emphasis added).

There Was No Pre-Pauline Oral Tradition

By Eli Kittim 🎓

When asked why Paul didn’t give us more details about Jesus’ existence, some scholars often use a common strawman argument that everyone already knew the story and so Paul didn’t have to write anything about it. But after thinking about this explanation for some time, I didn’t find it convincing. A key problem besetting the assumed pre-Pauline tradition is that it is a) based entirely on the gospel literature, which came much later, and b) it hasn’t been verified because there were no eyewitnesses and no firsthand accounts. Plus, the stories that we’re all familiar with (from the gospels) were not written until a few decades after Paul’s writings. So the life of Jesus was not written before, but after, Paul. Given that Paul’s knowledge of the story of Jesus is based entirely on “a revelation,” and that Paul himself admits that he didn’t receive it from man, nor was he taught it (Gal 1:11-12), it’s reasonable to assume that no one else knew the story prior to Paul’s writings, at least from a literary standpoint. After all, Paul was the first to write about it!

There are a lot of presuppositions that are implied by the oral Pre-Pauline-tradition hypothesis that most people aren’t aware of. Many people also presuppose that the gospels are historical, even though that has not been verified either. On the contrary, the fact that they were anonymously written, and that there were no eyewitnesses and no firsthand accounts, and that the events in Jesus’ life were, for the most part, borrowed from the Old Testament, seems to suggest that they were written in the literary genre known as “theological fiction.”

What is more, because the gospel texts are found at the beginning of the New Testament, people often presuppose that the gospels were the first Christian writings, and so they completely misunderstand the New Testament literary chronology. This presupposition leads to many other false assumptions that are very misleading and totally unrelated to the actual chronological development of the New Testament writings.

They have it all backwards❗️

What is more, because of the hypothetical Q source (for which there’s no evidence), even scholars often talk as if the gospels preceded the epistles, and so given that everyone already knew about the story, Paul didn’t have to mention all the details…

But wait just a second… ⛔️

The full-fledged story we usually refer to actually starts around 70 AD with Mark, and ends at the end of the first century with John. But surprise surprise, Paul is writing much much earlier than that. Paul’s letters are the FIRST Christian writings, which are written over two decades earlier (49-50 AD)! Paul’s writings are actually the EARLIEST Christian writings. So, presumably, no one knew the story yet, at least from a literary perspective. It was Paul’s task to tell the reader all about it.

But Paul failed to mention the pertinent information regarding the details of Jesus’ life, even though it is assumed that he was in a position to know this information. If Paul was expected to have all the pertinent information regarding the Jesus-story, and intending to write a complete account of these events, and if the details of the Jesus-story were important enough to deserve to be mentioned, then why didn’t Paul talk about any of them? Astoundingly, Paul didn’t mention any of the legendary elements that we find in the later embellishments of the 70s, 80s, and 90s. In Paul’s letters, there’s no nativity, no virgin birth, no shepherds, no star of Bethlehem, no magi, no census, no Elizabeth, no Zechariah, no John the Baptist, no flight to Egypt, no slaughter of the innocents, nothing about

“Jesus healing anyone,

casting out a demon, doing any other

miracle, arguing with Pharisees or

other leaders, teaching the multitudes, even

speaking a parable, being baptized, being

transfigured, going to Jerusalem, being

arrested, put on trial, found guilty of

blasphemy, appearing before Pontius Pilate

on charges of calling himself the King of the

Jews, being flogged, etc. etc. etc. It’s a very,

very long list of what he doesn’t tell us

about.” —Source credit: Bart D. Ehrman

This doesn’t mean that Paul is writing letters to people who already knew about the story.

It means that such a story didn’t exist. It was added later!

Conclusion

How is a supposed Aramaic story suddenly taken over, less than 2 decades after the purported events, by highly articulate Greeks and written about in other countries, such as Greece and Rome? None of the New Testament books were ever written in Palestine by Jews! That doesn’t make any sense and it certainly casts much doubt about the idea of a supposed Aramaic oral tradition.

In fact, most of the New Testament Books were written in Greece: Romans, 1 & 2 Corinthians, Galatians, 1 & 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, Titus, the Book of Revelation, and possibly others as well! To sum up, most of the New Testament Books were composed in Greece. Most of the epistles were penned in Greece and addressed to Greek communities. The New Testament was written exclusively in Greek, outside of Palestine, by “Greek” authors who copied the Greek Septuagint rather than the Hebrew Bible when quoting from the Old Testament. So where is the Aramaic tradition?

The Da Vinci Code Versus The Gospels

By Eli Kittim 🎓

Bart Ehrman was once quoted as saying: “If Jesus did not exist, you would think his brother would know it.” This is an amusing anecdote that I’d like to use as a springboard for this short essay to try to show that it’s impossible to separate literary characters from the literature in which they are found. For example, when Ehrman says, “If Jesus did not exist, you would think his brother would know it,” his comment presupposes that James is a real historical figure. But how can we affirm the historicity of a literary character offhand when the so-called “history” of this character is solely based on, and intimately intertwined with, the literary New Testament structures? And if these literary structures are not historical, what then? The fact that the gospels were written anonymously, and that there were no eyewitnesses and no firsthand accounts, and that the events in Jesus’ life were, for the most part, borrowed from the Old Testament, seems to suggest that they were written in the literary genre known as theological fiction. After all, the gospels read like Broadway plays!

Let me give you an analogy. Dan Brown writes novels. All his novels, just like the gospels, contain some historical places, figures, and events. But the stories, in and of themselves, are completely fictional. So, Ehrman’s strawman argument is tantamount to saying that if we want to examine the historicity of Professor Robert Langdon——who is supposedly a Harvard University professor of history of art and symbology——we’ll have to focus on his relationship with Sophie Neveu, a cryptologist with the French Judicial Police, and the female protagonist of the book. Ehrman’s earlier anecdote would be akin to saying: “if Robert Langdon did not exist, you would think Sophie would know it.”

But we wouldn’t know about Robert Langdon if it wasn’t for The Da Vinci Code. You can’t separate the character Robert Langdon from The Da Vinci Code and present him independently of it because he’s a character within that book. Therefore, his historicity or lack thereof depends entirely on how we view The Da Vinci Code. If The Da Vinci Code turns out to be a novel (which in fact it is), then how can we possibly ask historians to give us their professional opinions about him? It’s like asking historians to give us a historical assessment of bugs bunny? Was he real? So, as you can see, it’s all based on the literary structure of The Da Vinci Code, which turns out to be a novel!

By comparison, the historicity of Jesus depends entirely on how we view the literary structure of the gospel literature. Although modern critical scholars view the gospels as theological documents, they, nevertheless, believe that they contain a historic core or nucleus. They also think that we have evidence of an oral tradition. We do not! There are no eyewitnesses and no firsthand accounts. All we have about the life and times of Jesus are the gospel narratives, which were composed approximately 40 to 70 years after the purported events by anonymous Greek authors who never met Jesus. And they seem to be works of theological fiction. So where is the historical evidence that these events actually happened? We have to believe they happened because the gospel characters tell us so? It’s tantamount to saying that the events in The Da Vinci Code actually happened because Robert Langdon says so. But if the story is theological, so are its characters. Thus, the motto of the story is: don’t get caught up in the characters. The message is much more important! As for those who look to Josephus’ Antiquities for confirmation, unfortunately——due to the obvious interpolations——it cannot be considered authentic. Not to mention that Josephus presumably would have been acquainted with the gospel stories, most of which were disseminated decades earlier.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not trying to downplay the seriousness of the gospel message. I’m simply trying to clarify it. The gospels are inspired, but they were never meant to be taken literally. I’m also a believer and I have a high view of scripture. The message of Christ is real. But when will the Jesus-story play out is not something the gospels can address. Only the epistles give us the real Jesus!

People getting mad at Melanie for not being all goody-goody with Jon is so funny to me considering that out of all the main characters, including Georgie and Martin, she is the one who trusts him the most? The reason she keeps coming back to the Institute even though she always leaves there unsatisfied during S1-S3 is that even though Jon is horrible he at least listens (her own words) and she at no point in the show tries to stop or refuses to collaborate with Jon's plans out of pure tantrum. She has very strong comments about his leadership but she never stopped helping him when he needed it and vice versa. The only time she nope out of It was when she had just blinded herself and left the Institute, which is more than reasonable and neither parties holds any grudges about it.

YEAH this is actually such an interesting thing, cause there's a lot in tma about when a person consciously chooses to trust others and stay in consistent communication with them, and melanie almost never shuts that down with people. she's not really a secret keeper about anything big, it was a major deal when she didn't tell jon about her time in india because that isn't what she's usually like. she and jon are very similar people, but this is one of their major points of contrast: jon always has to slowly talk himself into trusting people, and even when he decides to there's often still major holes in the relationship, but melanie can really hate someone and still fundamentally be on their side and believe in their cause. she's the one who kept re-initiating their contact until jon knew she was reliable enough to serve as his spy in the archives, she really wanted to kill elias but trusted martin enough to back down when asked, and she was the one convincing georgie to help jon and martin get up the panopticon. ms king I am FREE on fridays.

When you understand that kids and teenagers being salty about literary symbolic analysis comes from a very real place of annoyance and frustration at some teachers for being over-bearing and pretentious in their projecting of symbolism onto every facet of a story but you also understand that literary analysis and critical thinking in regards to symbolism is extremely important and deserves to be not only taught in schools, but actively used by writers when examining their own work to see if they might have used symbolism unintentionally and to make sure that they are using symbolism effectively:

Hello I’m here to talk about an opinion that isn’t so much unpopular because people don’t like it, but because it is splitting hairs and basically an argument based in semantics that sane people reasonably do not waste their time caring about it.

I am neither sane nor reasonable and therefore think about this a lot, and get ready to pull out a soapbox and type the Text Wall of China any time I hear people offhandedly contradict this opinion, and so I have come here today to die on this molehill, and write the over-long post of my dreams, because fuck it, it’s my blog.

Drumroll please:

Sauron is not The Lord of the Rings

The Lord of the Rings is the main antagonist though, so furthermore,

Sauron is not the main antagonist of The Lord of the Rings

I internally go insane every time someone says “Sauron, the eponymous Lord of the Rings” or “The antagonist never actually appears in Lord of the Rings” or uses Lord of the Rings as an penultimate example of having a flat ‘evil for evil’s sake’ villain. This is mostly in YouTube videos so I’m not calling out anyone here.

So who is the Lord of the Rings? Where do I get this shit? Why should anyone care?

I will tell you in far too much detail under this cut, because I told you I was gonna be extra about it and this is already long enough to inflict on my followers without their consent.

First and foremost, Frodo is not the Lord of the Rings either. Let’s get that out of the way. Gandalf explicitly tells us that in Many Meetings (the first chapter in Rivendell in Fellowship), when Pippin greets a newly awakened Frodo with quintessential Fool of a Took™️ swagger.

‘Hurray!’ cried Pippin, springing up. ‘Here is our noble cousin! Make way for Frodo, Lord of the Ring!’

‘Hush!’ Said Gandalf from the shadows at the back of the porch. ‘Evil things do not come into this valley; but all the same we should not name them. The Lord of the Ring is not Frodo, but the master of the Dark Tower of Mordor, whose power is again stretching out over the world! We are sitting in a fortress. Outside it is getting dark.’

So that’s my theory busted right off the bat! Gandalf straight up tells us the Lord of the Ring is Sauron (‘the master of the Dark Tower of Mordor’ which is Sauron).

But I already told you, this is a hair-splitting semantics-based theory! He said Sauron was the Lord of the Ring. Not the Lord of the RingS. Yes, this whole theory revolves around a single letter difference between the title of the series and Gandalf’s statement, WHAT OF IT?

But in all seriousness. Tolkien was a linguist. There was no way this choice was not deliberate, not on something so important to the narrative. And there is a very important difference between what he is referring to when he uses ‘The Ring” singular, and “The Rings” plural. The Ring that Frodo carried to Mordor has it’s singular nature highly emphasized by the language that surrounds it. THE definite article Ring, the ONE Ring. Just the One. Singular Singular Singular.

The Rings (plural) refers to the rings of power which Celebrimbor wrought, with Sauron’s help, but Sauron is objectively not the Lord of those rings. Not the three Elven ones at least, which he never touched and only suspects the location of. Without his One Ring he has no power over the Three, and a big problem with him regaining his Ring is that he would gain power over those rings, the ringbearers, and the safe realms that had been wrought with them, basically crippling those with the power to resist him.

Him NOT having the Ring, and therefore NOT having lordship over all the rings, is a pretty major plot point. Like, it’s not a reach to say Sauron not having the Ring is what drives the entire story. And he is NOT the Lord of the Rings without it.

And he never gains it, so is the whole series named after Sauron’s aspirations, that the main characters are trying to prevent? I mean, from an angle yes. But also no.

Because while Pippin and Gandalf’s exchange is the closest we come in the text to seeing the title, let me show you the only place within the covers that “The Lord of the Rings” is presented, at least in my beat up third hand 70’s edition. It may not be formatted like this in other editions, but I still think it says something about how we are supposed to read the title:

[Image ID: Masking tape can clearly be seen holding together my poor abused copy of Fellowship, open to the title page. THE LORD OF THE RINGS is written across the top of the page in all caps, directly below it is the Ring Poem, as if The Lord of the Rings is a the title not only of the series but of the poem. /.End ID]

The One Ring is the Lord of the Rings, not Sauron, who is the Lord of the Ring.

“What?” Say imaginary naysayers in my head, “How can a Ring be a Lord? And why does this matter, if Sauron is the Lord of the Ring, doesn’t that make him the Lord of the Rings by proxy? Why are you wasting your and my time making an argument about this?”

I’m glad you asked imaginary naysayer, let me speak to your first point. How can a ring be a Lord? Well, like any good first time speechwriter, I’ve turned to Miriam Webster, and asked it to define a word we already know, in this case ‘lord.’

[Image ID: Screenshot of the Miriam Webster definition of ‘lord.’ The ones that are relevant are 1: One having power and authority over others. 1a: A ruler by hereditary right or preeminence to whom service and obedience are due. And 1f: One that has achieved mastery or that exercises leadership or great power in some area /.End ID]

In the poem, it is the Ring that is spoken of as ruling, not Sauron. Sauron is actually listed in the same position as all the others who receive rings, “The Dark Lord on his Dark Throne” occupying the same place in the sentence structure as the “the Elven-kings under the sky” and “the Dwarf-lords in their halls of stone” and “Mortal Men doomed to die.” It is the One Ring, not Sauron, who rules them all, fulfilling our first definition “A ruler by hereditary right or preeminence.” In this case it would be by right of preeminence, or superiority. The One Ring outclasses the other rings and thus dominates them, binding them to obedience and service. Gandalf calls it “the Master-Ring” when it is first revealed for what it is in Bag-End with the words appearing from the flame.

The Ring has it’s own will too. It’s repeatedly stated to be in control of Gollum when Gandalf is first telling us about it. I’m literally so spoiled for quotes about this that I was paralyzed with indecisiveness over what to use but let’s keep it simple with this one. It’s from Gandalf explaining why Gollum didn’t have the Ring allowing Bilbo to come upon it in the chapter “Shadows of the Past” from Fellowship:

‘It was not Gollum, Frodo, but the Ring itself that decided things. The Ring left him.’

So if Sauron is the Lord of the Ring, and the Ring is the Lord of the Rings, isn’t he Lord of the Rings by proxy? Yes, when he has the Ring. But also being the ruler of a lord doesn’t make the title of that lord your title, if that makes sense. People don’t call Aragorn the Prince of Ithilien, that’s Faramir’s title, Aragorn is King of the Reunited Kingdoms, he rules Ithilien, sure, but by proxy. Ithilien reports to Faramir who reports to Aragorn (I should be calling him Elessar since I’m talking about him as king, but whatever). If Aragorn lost the ability to contact Faramir or Ithilian, he would still theoretically be king there but he would have no practical control, just like Sauron with the Rings of Power.

Why does this matter? It mostly doesn’t. It does not change anything practically in the story at all.

But it matters to me, because it might help change perspective on the antagonist of LotR. It’s the Ring. Sauron is a force in the world, one the Ring is closely allied with, and from whom many of the obstacles come, but the entity that our protagonist is really fighting on every page is the Ring.

If Gandalf were the main character, or Aragorn, or almost anyone else on Middle Earth, Sauron would be the Primary Antagonist. But they are not. Frodo is the Primary Protagonist, and his struggle is NOT against Sauron, it is against the Ring.

If destroying the Ring had not destroyed Sauron, would Frodo have kept fighting in this war? NO! He had his task, and once it was done he was done, even if the world ended afterwards. Everything is driven by the Ring. The threat to the Shire comes from the presence of the Ring, so Frodo takes the Ring to Rivendell. The danger of the Ring is not neutralized by it being brought to Rivendell, so he continues his journey to destroy it once and for all. He doesn’t fight Sauron, he fights the Ring. He fights with himself to keep going in spite of the despair it levels on him, the poisonous words it whispers in his ear, the physical toll it takes on his body. He fights Boromir and Sam (not to the extent he does in the movie, but still a bit) and Gollum over the Ring. He negotiates with Faramir over the Ring.

And the Ring is SUCH a more interesting and nuanced villain to struggle with than Sauron. Sauron is representative of a force in the world. He controls events but never appears, because he acts as the source of all evil, it’s representation on earth (at least now Melkor is in the Void), but it is far more interesting to watch the effect he has on others than deal directly with a character that is so obviously in the wrong in every way. Making Sauron a physical character in LotR is like making the Devil a present character in basically any piece of media that deals with evil.

Evil at its purest isn’t that interesting, because it contains no conflict. Leaving Sauron as an offscreen player leaves us to see characters that are not pure evil struggle with that conflict.

The fascinating thing about the Ring is that it has no power outside of what you give it. But given enough time even the best people, like Frodo, will end up losing themselves to it, as it whispers in your ear with your own voice.

I want to go ballistic when people point to LotR and say it has a one dimensional villain. EVERYONE’S OWN VIOLENCE, DESPAIR AND THIRST FOR POWER IS THE VILLAIN OF LORD OF THE RINGS! Brought to the fore by a small unassuming golden trinket which just happens to also be the titular Lord of the Rings.

Honestly “The Ring is the Villain of LotR change my mind” should be its own big long post with lots of quotes and shit, the fact that the Ring is The Lord of the Rings just being a small point in it.

But unless you are a specific type of interested in story structure and stuff none of this is at all meaningful and it really, really doesn’t matter, so I’m gonna go.

Thanks for coming with me on this dumb journey.

Literary analysis is my JOB. And yeah, it's fun, but sometimes I want to storm into the comments under someone's analysis and explain some literary theory. Like Gale Dekarios explains magic.

To be clear: I encourage everyone to do it, just be ready for the nerds to start rambling XD

i will defend to the grave that literary analysis IS enjoyable and a valid hobby but it's amazing how a hyperfixation on The Character will have you writing essays for fun

This is a comment someone appended to a photo of two men apparently having sex in a very fancy room, but it’s also kind of an amazing two-line poem? “His Wife has filled his house with chintz” is a really elegant and beautiful counterbalancing of h, f, and s sounds, and “chintz” is a perfect word choice here—sonically pleasing and good at evoking nouveau riche tackiness. And then “to keep it real I fuck him on the floor” collapses that whole mood with short percussive sounds—but it’s still a perfect iambic pentameter line, robust and a lovely obscene contrast with the chintz in the first line. Well done, tumblr user jjbang8

I know I’m a few years late to the Gravity Falls party, but I can’t get over how effectively the Ford reveal flips the switch on Stan’s character. From what little I’d seen of the show on Tumblr before I watched it, I’d always assumed Stan was a pretty one-dimensional sleazy con man. And since it was a series aimed toward kids, I kind of assumed Stan wouldn’t get that much development or story outside of Dipper and Mabel. I figured if he did have an arc, it would be the pretty common “gruff bitter loner guy who doesn’t like people gets kids and learns to love them” storyline.

And for like the first half of the show, this kind of seemed to be the case, aside from the mystery surrounding whatever Stan was hiding in the basement.

And then the Ford reveal / backstory happens and you see Stan in a completely new light.

Stan isn’t a con man because he wants to be. He’s a con man out of necessity - first because he was kicked out of his house and forced to make it on his own at 18, and then because it was helping him work to bring his brother back. He doesn’t just run the mystery shack because he likes to lie to people and swindle them out of their money - he does it because he needed a way to make money and keep the shack while trying to figure out a way to reopen the portal. He has a fake identity because he needed to keep people from snooping around looking for Stanford and the easiest way to do that was to take his place.

All the things that make you think he’s selfish and shady throughout the first half of the series are revealed to be because he’s a desperate, heartbroken man who wants to bring his brother back. He isn’t the traditional gruff guy who doesn’t love anyone until some rambunctious kids come into his life at all - he loves his brother so much that literally everything he does is to get him back. And he lies to the kids in an effort to protect them and keep anything bad from happening to them like it did to his brother.

Great twists / mystery reveals don’t just take the story in a new direction - they cast new light on everything that has come before. And Gravity Falls does that so well.

Just look at one of the first episodes in the series where Mabel makes a wax figure of Stan and Stan appears to fall in love with it and mourns it when it melts, going as far to host a funeral for it. Without knowing Stan’s backstory, this whole storyline just feeds into our view of Stan as a self-centered, ridiculous person. It’s ridiculous he would cherish a wax figure of himself. It’s so egotistical that he would host a funeral for it when it died and get honestly choked up about it.

But then you learn that Stan lost his twin brother and that whole storyline doesn’t really feel like the story of a selfish, egotistical man anymore. It’s the story of a man who felt like he got his brother back again momentarily and then had to lose him all over again.

That’s an effective twist. You can’t learn about Stan’s backstory and then go back and view him the same way you did before it.

Here's my post about pjo trauma:

And my post about women and violence in media:

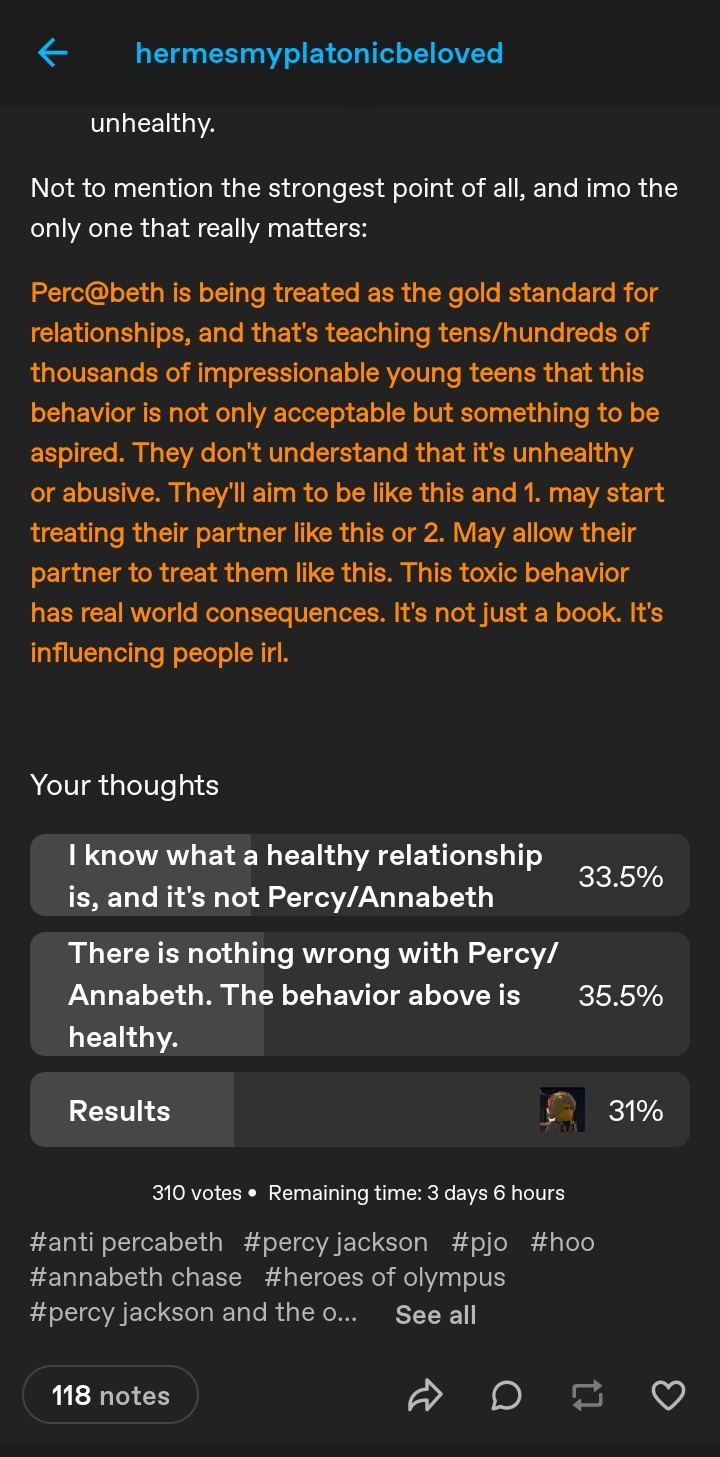

So I saw @hermesmyplatonicbeloved 's post and had some thoughts. I agree and disagree. I am a percabeth fan but I also know that some of it is screwy, and if you are familiar with my blog, you know this. I think RR screwed up and wrote out a LOT of trauma, I think he really should have dealt with that better. I think it's not good that he wrote trauma and mental issues and abuse into the foundation of many characters and then has ignored it when it became convenient for the plot.