457 posts

The Real Revelation Of The Writer (as Of The Artist) Comes In A Far Subtler Way Than By Autobiography;

The real revelation of the writer (as of the artist) comes in a far subtler way than by autobiography; and comes despite all effort to elude it; ... For what the writer does communicate is his temperament, his organic personality, with its preferences and aversions, its pace and rhythm and impact and balance, its swiftness or languor ... and this he does equally whether he be rehearsing veraciously his own concerns or inventing someone else’s.

Shakespeares Imagery And What It Tells Us (1923)

by Spurgeon, Caroline. F.

More Posts from Yoswenyo

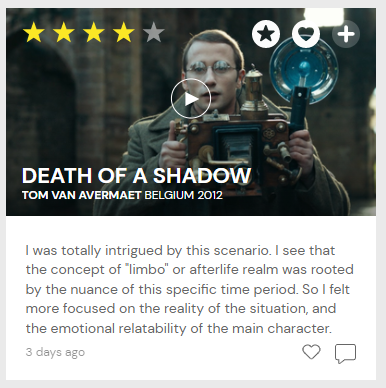

------“I thought this concept was pretty enticing, given the stakes. It really expressed how love grounds people’s existence. Wish it had more time to flesh out the characters.”

Each of the Major arcana reflect a level of awareness that we achieve through life. The numerological values express a progression of spiritual states rather than a sequential process.

In order to work with the Planets in your chart, or even begin to understand the universal laws, you have to receive the multitude of your own spiritual potential.

If you don’t know which cards these descriptions are for, I made a PDF to help you out.

They were conscious that when the creative impulse was given a free rein, a power flowed through their poetry. This happened when they created imaginary worlds and expressed these fleeting visions in a concrete form. The only way they could make the imaginary world intelligible to the reader, and to themselves, was through the imagery. The imagery was a link between the known and the unknown; it was in fact the stairway to the stars.

The Imagery of Thomas De Quincy's Impassioned Prose - Dwyer (1965)

Without a basis of the dreadful, there is no perfect rapture. It is in part through the sorrow of life, growing out of dark events, that this basis of awe and solemn darkness slowly accumulates.

The Imagery of Thomas De Quincy's Impassioned Prose - Dwyer (1965)