DC Home Rule - Tumblr Posts

Charles Wesley Harris, Congress and the Governance of the Nation's Capital

Donald Rowat, a Canadian political scientist, and Charles Wesley Harris both study federal capital cities worldwide. Apparently there is a literature surrounding the tension between local and federal political power in these cities. I also need to get my hands on Harris' Perspectives of Political Power in the District of Columbia : the Views and Opinions of 110 Members of the Local Political Elite.

Definitely a sub-field worth looking into.

The full text of the legislation granting District residents the right to elect their own mayor and city council.

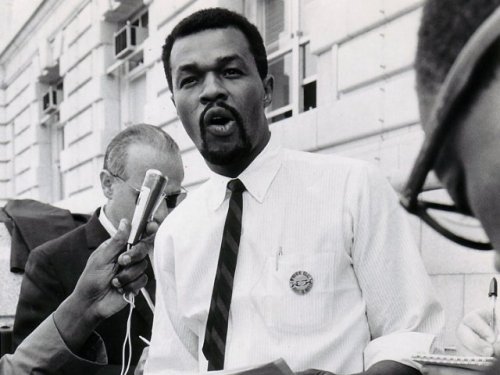

This collection contains correspondence, news releases, booklets, articles, brochures, statements, meeting files, briefing books, memorabilia, newsletters, photographs, negatives, slides, bills, and hearing files. These materials date from 1941-90 with the bulk of the records falling between 1960-90.

This collection of materials was generated during thirty-nine years of community, religious and political service. Fauntroy was an advocate of civil and political rights. A former congressman, Fauntroy served the people of the District of Columbia through various roles. Since 1959, Fauntroy has been the pastor of New Bethel Baptist Church. His exceptional leadership in community affairs led Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., founder of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), to appoint Fauntroy as the director of the Washington D.C. Bureau of SCLC. Through this position, he served as the coordinator of various historic events associated with the organization such as the 1963 March On Washington for Jobs and Freedom and the 1965 March from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

Fauntroy was the first vice chairman appointed to the Washington D.C. City Council. After years of promoting voting rights and representation for citizens of the District, Fauntroy served as the representative of Washington, D.C. in the United States Congress for twenty years. He was an advocate of urban renewal in the District of Columbia, and was a founder and director of the Shaw Urban Renewal Project and the Model Inner City Community Organization (MICCO).

Organized in six series: General files, Affiliations and organization files, Campaign files, Congressional committee files, New Bethel Baptist Church files, and Oversize files.

We want to free D.C. from our enemies, the people who make it impossible for us to do anything about lousy schools, brutal cops, slumlords, welfare investigators who go on midnight raids, employers who discriminate in hiring and a host of other ills that run rampant through our city.

Marion Barry, speaking for the Free DC Movement, 1966 (Gillette 190)

Super score! Writings by Sam Smith, one of the founders of the DC Statehood Party.

An article published by DC Statehood Party founder Sam Smith. The graphic in and of itself is great for someone like me who has a tough time distilling down to a timeline.

So I figured out the name of the law that granted the District the right to elect its own board of education: District of Columbia Elected Board of Education Act, approved April 22, 1968; Public Law 90-292, 82 Stat. 101. This link is President Johnson's remarks upon signing the bill.

It's important to note that Dr. King was assassinated on April 4; riots erupted in Washington and continued through April 12. After some public uncertainty about whether the protest would continue, the SCLC's Poor People's Campaign began on the National Mall on May 12. This is the atmosphere in which this bill was signed, and it's equally important to note that after an oblique reference to the city "in crisis," President Johnson openly calls for congressional representation and home rule for the District.

This GPO pamphlet also seems like it may be important later on, although I'm unsure of how to use it now.

An article by Jason I. Newman and Jacques B. DePuy, published in the Spring 1975 edition of the American University Law Reviewl (volume 24, number 3). It offers a legislative history of the District of Columbia, with references to specifically named laws and statutes; this is followed by a lengthy, in-depth, and rather dense analysis of the Home Rule Act of 1973.

rough draft of new intro

In the public mind, the civil rights movement exists as a phenomenon that revolutionized the still-rural U.S. South between 1954 and 1965, led by courageous and deeply moral men who confronted violent racism with nonviolence and civil disobedience, driven by their belief that the time for African-American rights had finally come. But in the last two decades, professional historians have begun to challenge this categorization, pushing the temporal, geographic, tactical, institutional and gendered boundaries of the traditionally drawn movement. Long civil rights scholars such as Jacqueline Dowd Hall, Peniel Joseph and Martha Biondi have all explored black freedom struggles outside the South and before its rhetorically nonviolent battles for integration. Meanwhile, urban historians like Thomas Sugrue, Robert O. Self and Matthew Lassiter have re-injected black activism into the narrative of post-WWII urban growth. However, none of these works have addressed the central question of what these struggles for equality might mean in the nation’s capital, where its residents of all races have long been constitutionally denied the right to vote.

Despite much excellent work on relevant themes such as grassroots and cross-racial coalitions, the role of federal intervention, and the distinctiveness of Northern and Western movements, scholars examining the long civil rights movement and post WWII cities have not fully explored the District of Columbia and its century-old battle for voting rights. Yet without such an understanding, we are left with an inadequate analysis that ignores both the Mid-Atlantic region between North and South and the federal government’s remarkable power to decide who should have rights.

This study will remedy the gap in the literature by examining post-WWII racial politics in the District in order to more fully elucidate the city’s previously unrecognized relationships with national civil rights organizations and the executive and legislative branches of the federal government. This study will focus particularly on Washington in the years between 1945 and 1973, when the U.S. Congress finally granted residents some means to home rule. Through a close analysis of the role played by African-American activists in the District’s extended battle against Congress for voting rights, I will show that in contrast to previous assumptions about the exceptionality of the District, in fact the work of these activists should be considered one piece of the larger nationwide push for black political power.

Committee papers and bill files from the House of Representatives' Committee on the District of Columbia. Of special interest are those in the third set (1947-1968), which include documents pertaining to District home rule.

Records from the Senate's Committee on the District of Columbia from 1816-1972. Of special note are records from the Radical Republican-controlled Senate of the Reconstruction era (the Senate fought for Kate Brown, one of their employees, to be able to ride on whites-only trains) and records on the nonstop flow of home rule bills considered after the LEgislative Reorganization Act of 1946.

the latest intro

So the last intro draft has been moved to my "Contribution to the Field" section. Here's the new intro:

While the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 ensured that African-Americans would have the right to vote granted by the Fifteenth Amendment, this legislation did little for the voting prospects of the residents of the District of Columbia. Denied the right to elect their own local government or representatives to the U.S. Congress, Washingtonians of all races had only been allowed to vote for president the previous year, in the first presidential election since Congress passed the Twenty-Third Amendment. Although Washington had long been home to active movements for legislative autonomy from Congress and African-American civil rights, these movements remained largely separate until the District became a majority-minority city in the 1950s. Despite early civil rights successes in the 1940s and 1950s and agitation for District voting rights by national organizations like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the desire for home rule remained largely unrealized until the late 1960s and early 1970s - after the alleged end of the civil rights movement. How did the city’s changing demographics and relationship with the national civil rights struggle impact the century-old battle for home rule and the city’s relationship with the U.S. Congress? How does the District of Columbia fit into the larger narrative of the black protest movement?

Marion Barry: The King of DC - Marcus Simon