Author of “The Little Book of Revelation.” Get your copy now!!https://www.xlibris.com/en/bookstore/bookdetails/597424-the-little-book-of-revelation

447 posts

A Response To Tiff Shuttlesworths The Last Trumpet In Revelation

A Response to Tiff Shuttlesworth’s “The Last Trumpet in Revelation”

Eli Kittim

Tiff Shuttlesworth is the President/Founder of Lost Lamb Evangelistic Association at Northpoint Bible College and Seminary. He is also a well-known pastor and Bible prophecy teacher who holds to the pretribulational view of the rapture. His videos on bible prophecy are very popular on YouTube and elsewhere. Recently, I came across a video by Tiff Shuttlesworth, entitled, “The Last Trumpet in Revelation.” In that video, Shuttlesworth took issue with the mid and post tribulation rapture views and publicly denounced them as “poor scholarship.”

In this video, Tiff Shuttlesworth says that the last (or 7th) trumpet in Rev 11:15 is not the same as “the last trumpet” in 1 Cor. 15:51-52, and that it also bears no relation to “the trumpet of God” in 1 Thess. 4:16-17, chronologically or otherwise. He is in error. They are the same. He offers some tendentious reasons why this is so, but they are all based on a basic misunderstanding and misinterpretation of scripture. He says that 1 Cor. 15 is talking about the church, whereas Rev 11 is referring to the judgments of God, and he claims that not only is the timing of these events different but also “the last trumpet” in 1 Cor. 15:51-52 is not the same as the last (or 7th) trumpet in Rev 11.15. As will be shown, this is not the case. The reason he tries to dissociate the last trumpet of 1 Cor. 15:51-52 from the 7th and final trumpet in the Book of Revelation is because Rev ch. 11 implies that the last trumpet takes place AFTER the great tribulation, not before. It is similar to Matt. 24:29-31 (NASB) in which the rapture of the elect occurs AFTER, not before, the great tribulation. Notice that the rapture will begin “with a great trumpet blast” (italics mine):

“But immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from the sky, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken. … and they will see the Son of Man coming on the clouds of the sky with power and great glory. And He will send forth His angels with a great trumpet blast, and they will gather together His elect from the four winds, from one end of the sky to the other.”

So, because Tiff Shuttlesworth is a pre-tribulationist, he obviously wants to dismiss this piece of evidence, which challenges his pre-tribulation rapture view. Naturally, he tries to argue that these passages are diametrically opposed to each other. But this is poor scholarship. As we dig deeper, we realize that they’re very much connected. Moreover, since they are inspired, we must read the books of the Bible in “canonical context,” rather than as separate books that are unrelated to each other.

It is interesting to note that Rev 11, just before introducing the 7th trumpet, mentions the rapture of the two witnesses. And it follows with a celebration of the church triumphant, in heaven, which foresees the reign of Christ. Interestingly enough, Rev 11 makes mention of the esteemed tribulation saints, otherwise known as “the twenty-four elders”——whom we know from chapter 4—-in order to inform us that the great tribulation, the general resurrection of the dead, and the rapture are in view. Revelation 11:18 reads thusly:

“and the time came for the dead to be judged, and the time to reward Your bond-servants the prophets and the saints.”

This is a direct reference to the general resurrection of the dead, that we’re all familiar with from 1 Thess. 4:15-17, which happens simultaneously with the rapture, when the faithful will be rewarded with immortality and glory (theosis). They will shine. There is no other resurrection of the dead (Dan. 12:1-2). This is it! Similarly, 1 Thess. 4:16-17 says that Christ will appear for the resurrection and the rapture with the sound of God’s trumpet:

“For the Lord Himself will descend … with a shout, with the voice of the archangel and with the trumpet of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. Then we who are alive, who remain, will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air.”

First Corinthians 15:51-52 further clarifies that all this will take place “at the last trumpet”:

“Behold, I am telling you a mystery; we will not all sleep, but we will all be changed, in a moment, in the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet; for the trumpet will sound, and the dead will be raised imperishable, and we will be changed.”

So, when is the last trumpet? According to Rev 11:15, the last (or 7th) trumpet is blown during the time period when the Lord’s Messiah begins to reign over the entire world. So, it is obviously a period that takes place AFTER the great tribulation, not before. Rev 11:15-17 reads:

“Then the seventh angel sounded; and there were loud voices in heaven, saying, ‘The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of His Christ; and He will reign forever and ever.’ And the twenty-four elders, who sit on their thrones before God, fell on their faces and worshiped God, saying, ‘We give You thanks, Lord God, the Almighty, the One who is and who was, because You have taken Your great power and have begun to reign.’ “

-

lucyshoresmade liked this · 9 months ago

lucyshoresmade liked this · 9 months ago

More Posts from Eli-kittim

What if the Crucifixion of Christ is a Future Event?

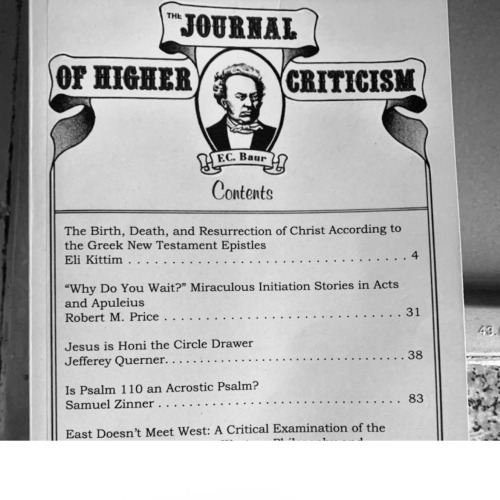

Read the PDF of my article, published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 13, no. 3 (2018).

Matthew 24:42

📚 Eli of Kittim Quotes on YouTube 📚

♦️◾️🟢🔅💥✨🪐💫🌍⚡️✝️⚫️🔸

Biographizing the Eschaton: The Proleptic Eschatology of the Gospels

Eli Kittim

The canonical epistles strongly indicate that the narratives concerning the revelation of Jesus in the New Testament (NT) gospel literature are proleptic accounts. That is to say, the NT gospels represent the future life of Jesus as if presently accomplished. The term “prolepsis,” here, refers to the anachronistic representation of Jesus’ generation as if existing before its actual historical time. Simply put, the gospels are written before the fact. They are conveyed from a theological angle by way of a proleptic narrative, a means of biographizing the eschaton as if presently accomplished. In other words, these are accounts about events that haven’t happened yet, which are nevertheless narrated as if they have already occurred.

By contrast, the epistles demonstrate that these events will occur at the end of the age. This argument is primarily founded on the authority of the Greek NT Epistles, which affirm the centrality of the future in Christ’s only visitation! In the epistolary literature, the multiple time-references to Christ being “revealed at the end of the ages” (1 Pet. 1.20; cf. Heb. 9.26b) are clearly set in the future, including his birth, death, and resurrection (see Gal. 4.4; Eph. 1.9-10; Rev 12.5). It is as though NT history is written in advance (cf. Isa. 46.10)!

The Proleptic versus the Prophesied Jesus

The historical view is extremely problematic, involving nothing less than a proleptic interpretation of Jesus. It gives rise to numerous chronological discrepancies that cannot be easily reconciled with eschatological contexts of critical importance. What is even more troubling is that it evidently contradicts many explicit passages from both the Old and New Testaments regarding an earthly, end-time Messiah and uses bizarre gaps and anachronistic juxtapositions in chronology in order to make heterogeneous passages appear homogeneous (e.g. Job 19.25; Isa. 2.19; Dan. 12.1—2; Zeph. 1.8—9, 15—18; Zech. 12.9—10; Lk. 17.30; Acts 2.17—21; 2 Thess. 2.1—3, 7—8; Heb. 1.1—2; 9.26; 1 Pet. 1.20; Rev 12.5, 7—10).

Intertextuality in the Gospels

The canonical gospel accounts add another level of intertextual reference to the Old Testament (OT). Almost every event in Jesus’ life is borrowed from the OT and reworked as if it’s a new event. This is called “intertextuality,” meaning a heavy dependence of the NT literature on Hebrew Scripture. A few examples from the gospels serve to illustrate these points. It’s well-known among biblical scholars that the Feeding of the 5,000 (aka the miracle of the five loaves and two fish) in Jn 6.5-13 is a literary pattern that can be traced back to the OT tradition of 2 Kings 4.40-44. The magi are also taken from Ps. 72.11: “May all kings fall down before him.” The phrase “they have pierced my hands and my feet” is from Ps. 22.16; “They put gall in my food and gave me vinegar for my thirst” is from Ps. 69.21. The virgin birth comes from a Septuagint translation of Isa. 7.14. The “Calming the storm” episode is taken from Ps. 107.23-30, and so on & so forth. Is there anything real that actually happened which is not taken from the Jewish Bible? Moreover, everything about the trial of Jesus is at odds with what we know about Jewish Law and Jewish proceedings. It could not have occurred in the middle of the night during Passover, among other things.

There is only One Coming, not Two

The belief in the two comings of Christ equally contradicts a number of NT passages (e.g. 1 Cor. 15.22—26, 54—55; 2 Tim. 2.16—18; Rev 19.10; 22.7, 10, 18—19), not to mention those of the OT that do not separate the Messiah’s initial coming from his reign (e.g. Isa. 9.6—7; 61.1—2). Rather than viewing them as two separate and distinguishable historical events, Scripture sets forth a single coming and does not make that distinction (see Lk. 1.31—33). Indeed, each time the “redeeming work” of Messiah is mentioned, it is almost invariably followed or preceded by some kind of reference to judgment (e.g. “day of vengeance”), which signifies the commencement of his reign on earth (see Isa. 63.4). In 2 Thess 2, the author implores us not to be deceived by any rumors claiming that the Lord has already appeared: “to the effect that the day of the Lord is already here” (v. 2; cf. v. 1). His disclaimer insists that these conventions are divisive in view of the fact that they profess to be Biblically based, “as though from us” (v. 2), even though this is not the official message of Scripture.

Why Does the New Testament Refer to Christ’s Future Coming as a “Revelation”?

Why do the NT authors refer to Christ’s future coming as a “revelation”? The actual Greek word used is ἀποκάλυψις (apokalupsis). The English word apocalypse comes from the Greek word apokalupsis, which means “revelation.” The term revelation indicates the disclosure of something that was previously unknown. Thus, according to the meaning of the term revelation, no one knows the mystery or secret prior to its disclosure. Therefore, we cannot use the biblical term “revelation” to imply that something previously known is made known a second time. That’s not what the Greek term apokalupsis means. If it was previously revealed, then it cannot be revealed again. It’s only a revelation if it is still unknown. Thus, the word “revelation” necessarily implies a first time disclosure or an initial unveiling, appearing, or manifestation. It means that something that was previously unknown and/or unseen has finally been revealed and/or manifested. Thus, a revelation by default means “a first-time” occurrence. In other words, it’s an event that is happening for the very first time. By definition, a “revelation” is never disclosed twice.

Accordingly, the NT verses, which refer to the future revelation of Christ, never mention a second coming, a coming back, or a return, as is commonly thought. See the following verses:

1 Cor. 1.7-8; 4.5; 15.23; Phil. 1.6; 2.16; Col. 3.4; 2 Thess. 1.7; 1.10; 2.1-2; 1 Tim. 6.14; Titus 2.13; Jas. 5.7; 1 Pet. 1.13; 1 Jn. 2.28; Rev 1.1; 22.20.

In the aforementioned verses, a second coming is nowhere indicated. Conversely, Jesus’ Coming is variously referred to as an appearance, a manifestation, or a “revelation” in the last days, which seems to imply an initial coming, a first coming, and the only coming. Surprisingly, it’s not referred to as a return, a coming back, or a second coming. As N.T. Wright correctly points out, the eschatological references to Jesus in the New Testament don’t mention a second coming but rather a future appearance or manifestation. Not only do the NT writers refrain from calling Jesus’ future visitation “a second coming,” but, conversely, they further indicate that this is his first and only advent, a momentous event that will occur hapax (“once for all”) “in the end of the world” (Heb. 9.26 KJV), or “at the final point of time” (1 Peter 1.20 NJB). None of the NT authors refer to the future visitation of Christ as a second coming. It’s as though these communities expected Jesus to appear for the first time in the end of the world! The takeaway is that the NT is an apocalypse. It’s not a history.

Is the Authority of Scripture Biblical?

Eli Kittim

I have a high view of Scripture. But my authority is a Person, not a Book. My authority is God himself, as he reveals to me his will and purpose through spiritual communications. It’s one thing to say that the Bible is “authoritative,” in the sense that it’s reliable and truthful. But it’s quite another thing to say that it’s our highest authority. I think people mistakenly conflate the authority of Scripture with Cessationism, the Calvinist doctrine that spiritual gifts and prophecy ceased with the Apostolic Age. They often cite Jude 1:3 for support. But all that verse says is that “the faith” was revealed to us at some point in human history. It doesn’t say that the Godhead went out of business, took a Sabbatical, or died and left a will. The phrase—“the faith delivered once for all to God's people”—can be disambiguated by examining the context. The other passage cessationists love to quote is 1 Cor. 13:9-10. But all it says is that “we know in part and prophesy in part” because “when the perfect comes, the partial will be done away with.” But not before the complete comes. That’s the key! It doesn’t say that prophecy has ceased. That would be a misinterpretation. Besides, Acts 2:17 says that people in the end times will prophesy and see visions.

Many people are confusing Scripture’s inspiration, revelation, truthfulness, and inerrancy with the concept of “authority,” which the Oxford languages dictionary defines as “the power or right to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience.” In short, our highest authority is not the Church, tradition, councils, committees, or even the Bible itself. Our highest authority is Jesus Christ! In Matt. 28:18 (NASB), Christ says:

“All authority in heaven and on earth has

been given to Me”

Where does 2 Tim. 3:14–16 mention the authority of Scripture? It says that “the sacred writings … are able to give you the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus.” In other words, Scripture gives us wisdom and leads us to salvation which can only be found in Christ Jesus. The fact that Scripture is “inspired” doesn’t mean it represents the final authority. 2 Tim. 3:14–16 reads:

“continue in the things you have learned

and become convinced of, knowing from

whom you have learned them, and that

from childhood you have known the sacred

writings which are able to give you the

wisdom that leads to salvation through faith

which is in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is

inspired by God and beneficial for teaching,

for rebuke, for correction, for training in

righteousness.”

The fact that Scripture is God-breathed (2 Tim. 3:16) doesn’t mean that the Bible has the final say in all matters. The Spirit that inspired the Bible is the ultimate authority on all matters, not the Bible. Scripture itself does not claim to have all authority. Jesus does.

Moreover, the concept of the Sufficiency of Scripture implies that Scripture itself is all we need to interpret Scripture. But Scripture can be interpreted in 30,000 different ways. Just look at all the Protestant denominations that split due to interpretative differences. Thus, Scripture is neither sufficient to interpret itself, nor is it the final authority. Without the Holy Spirit to illuminate us, we will inevitably misinterpret it (Jn 16:13)!

Where does 2 Pet. 1:20–21 mention the authority of Scripture?

“But know this first of all, that no prophecy

of Scripture becomes a matter of

someone’s own interpretation, for no

prophecy was ever made by an act of

human will, but men moved by the Holy

Spirit spoke from God.”

All it says is that prophecy and its interpretation should be revealed by the Holy Spirit, not interpreted by human beings. If anything, it demonstrates the insufficiency of Scripture!

The fact that the Bible contains the Word of God doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the final authority, or that it’s sufficient in and of itself, so that we don’t need anything else. If the Bible is entirely “sufficient” and adequate for all purposes, we wouldn’t need to be reborn. All we would need to do is read our Bibles. But Scripture cannot save anyone. Jesus does. The Spirit is what we need. We can be saved by the Spirit without the Bible. But we can’t be saved by the Bible without the Spirit.

The Bible does not attest to its own authority. Revelation of the Word does not mean ultimate Authority. The fact that God’s Word is true (Jn 17:17) doesn’t mean that the Bible is the highest authority in our lives. As Christ said, it is the Spirit that perfects us, not the Scriptures (Jn 16:13). Luke 24:49 reads:

“But remain … until you have been clothed

with power from on high”

John 3:5 says categorically and unequivocally:

“unless someone is born of … the

Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.”

Likewise, Romans 8:9 puts it thusly:

“But if anyone does not have the Spirit of

Christ, he does not belong to Him.”

In John 5:39-40, Jesus demonstrates the insufficiency of Scripture by saying the following:

“You examine the Scriptures because you

think that in them you have eternal life; and

it is those very Scriptures that testify about

Me; and yet you are unwilling to come to Me

so that you may have life.”

When Jesus says that all will be accomplished according to his Word (Matt. 5:18), he’s talking about prophecy, not the authority of Scripture. I’m not suggesting that Scripture errs or is contradictory. Absolutely not! But let’s not confuse the issues. The fact that the Bible contains the Word of God doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s our final authority, or that it’s entirely sufficient. That would be equivalent to Bibliolatry. The Bible is not a paper Pope. Truth and trustworthiness is one thing. Authority is another.