How To Write Better Descriptions

How to write better descriptions

1. Avoid weak words

Compare these:

He ate the sandwich

She walked towards the lake.

to these:

He devoured the sandwich

She strolled towards the lake.

Which sentences tells you more? The latter ones. Why? Because devoured and strolled are stronger words than ate and walked. They’re more specific, so they give you more information. To get across the same information with ate and walked, you’d have to add more words: ‘she walked slowly,’ ‘he ate quickly.’

Obviously this isn’t saying you can only ever use strong words–that would likely quickly devolve into purple prose–but If your descriptions only ever include general terms: ‘it smelled good’ ‘he walked over to greet her’ etc. you’re making it harder for your reader to get an accurate picture of whatever is happening in your scene.

So how do you spot a weak word? The biggest problem with (and easiest way to spot) a weak word is that it needs support from other words to really get its meaning across. If you find yourself adding adverbs and adjectives to a term, question whether or not there’s a more concise way to get your point across instead.

2. Be Specific Where Details Are Important

This isn’t to say you should describe everything in every scene in perfect detail, but being specific matters.

Which is more engaging?

He devoured the sandwich

The book smelled magical.

or

He devoured the sandwich, stopping only to lick up the melted cheese that seeped through his fingers and ran down his palm.

The book smelled like a sunlit afternoon.

Again, the latter ones. They take you into the scene. They evoke the senses. It’s the difference between telling and showing. Devoured is a strong verb, but it doesn’t give us a clear image of what is happening. Showing the character licking away the cheese gives the reader a sense of the desperation and hunger of the action. Evoking a sunlit afternoon is evoking your reader’s memories of their own sunny afternoons.These examples are statements with evidence. They provide details.

You want to invite your reader into the scene, not give them a summary of the events.

Additionally, specifics make the world feel real. They convince readers that the world actually exists. They keep the story in your readers’ minds once they’ve finished reading.

This being said, don’t pull a GRRM and describe every meal your characters eat. Some things just aren’t that important. There are MANY occasions when it’s okay to tell instead of show.

3. Remember the point of view.

Who is giving the description?

If you’re writing in 1st person or 3rd person limited, remember how your character feels about what you’re describing. If you’re describing a strawberry field, a person who was raised on a strawberry farm is going to see it differently than someone who is deathly allergic to strawberries, who is going to see it differently from a Beatles fanatic.

Maybe the Beatles fanatic is deathly allergic to strawberries and this field brings up a whole bucketful of conflicting emotions.

Which is all to say:

Good descriptions reveal character as well as scene.

If this description is coming from a character’s point of view: what is that point of view? What is this scene making your character feel? Don’t let your narrator slip away from the page.

This connects to my last point.

4. Remember why you’re including it.

Novel writing is persuasive writing. It’s an exercise in persuading your reader that your story is true, that your characters are real people. It’s an exercise in persuading your readers to feel what you want them to feel.

(There’s a well-known quote about this somewhere, but I can’t remember it exactly.)

Every description must add to the story. It should be doing something: working for some larger goal, advancing the plot, revealing character.

Maybe you’re describing a house because you want your reader to see why your character doesn’t want to move.

Maybe you’re describing this lovely-smelling book because you want the reader to know that it’s important to the character. That her favorite memories are of reading it in the attic of her grandmother’s house.

When you’re writing out a description, identify its purpose and make sure it fulfils it.

It’s okay if at first you don’t know how the house makes the character feel, or if she’s running or strolling towards the lake, or why the book is so important. Sometimes you just know it’s there. That something happened. Usually things become clearer as you write further and get to know the story and characters yourself.

Once you do know what you’re trying to say with your story, make sure you say it with every chapter, every description, and every word.

-

mofflani liked this · 7 months ago

mofflani liked this · 7 months ago -

ch3rubpuppi liked this · 7 months ago

ch3rubpuppi liked this · 7 months ago -

sayo-nora liked this · 7 months ago

sayo-nora liked this · 7 months ago -

miriamladyvoid liked this · 7 months ago

miriamladyvoid liked this · 7 months ago -

unstable-kiwi liked this · 8 months ago

unstable-kiwi liked this · 8 months ago -

starvedveins liked this · 8 months ago

starvedveins liked this · 8 months ago -

thatcassieblake liked this · 9 months ago

thatcassieblake liked this · 9 months ago -

myemailsucksdontmindit liked this · 9 months ago

myemailsucksdontmindit liked this · 9 months ago -

dolourstories liked this · 9 months ago

dolourstories liked this · 9 months ago -

ijustpickedarandomsuggestion liked this · 9 months ago

ijustpickedarandomsuggestion liked this · 9 months ago -

s3xybimbo liked this · 10 months ago

s3xybimbo liked this · 10 months ago -

cxldwell liked this · 10 months ago

cxldwell liked this · 10 months ago -

strqwxberrii liked this · 10 months ago

strqwxberrii liked this · 10 months ago -

thelostinthebooks liked this · 10 months ago

thelostinthebooks liked this · 10 months ago -

crudmuffintheevil liked this · 10 months ago

crudmuffintheevil liked this · 10 months ago -

crudmuffintheevil reblogged this · 10 months ago

crudmuffintheevil reblogged this · 10 months ago -

simsevil liked this · 10 months ago

simsevil liked this · 10 months ago -

theundeadmortal liked this · 11 months ago

theundeadmortal liked this · 11 months ago -

fallsheavy liked this · 11 months ago

fallsheavy liked this · 11 months ago -

etherealmote liked this · 11 months ago

etherealmote liked this · 11 months ago -

kalypso227 liked this · 11 months ago

kalypso227 liked this · 11 months ago -

worldofomi liked this · 11 months ago

worldofomi liked this · 11 months ago -

sweetvalentineheart liked this · 11 months ago

sweetvalentineheart liked this · 11 months ago -

rtc0204 reblogged this · 1 year ago

rtc0204 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

rtc0204 liked this · 1 year ago

rtc0204 liked this · 1 year ago -

valiciaspudng liked this · 1 year ago

valiciaspudng liked this · 1 year ago -

arandominternetwriter reblogged this · 1 year ago

arandominternetwriter reblogged this · 1 year ago -

neptunecookies liked this · 1 year ago

neptunecookies liked this · 1 year ago -

writing-bug22 reblogged this · 1 year ago

writing-bug22 reblogged this · 1 year ago -

abookishdreamer reblogged this · 1 year ago

abookishdreamer reblogged this · 1 year ago -

abookishdreamer liked this · 1 year ago

abookishdreamer liked this · 1 year ago -

yujinniestuff liked this · 1 year ago

yujinniestuff liked this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit liked this · 1 year ago -

atnaturesloopholed liked this · 1 year ago

atnaturesloopholed liked this · 1 year ago -

cartoonsfillup reblogged this · 1 year ago

cartoonsfillup reblogged this · 1 year ago -

cartoonsfillup liked this · 1 year ago

cartoonsfillup liked this · 1 year ago -

writeshine reblogged this · 1 year ago

writeshine reblogged this · 1 year ago -

casualtriumphinfluencer liked this · 1 year ago

casualtriumphinfluencer liked this · 1 year ago -

ninifever1006 liked this · 1 year ago

ninifever1006 liked this · 1 year ago -

deerpines liked this · 1 year ago

deerpines liked this · 1 year ago -

otispantsuit liked this · 1 year ago

otispantsuit liked this · 1 year ago -

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago

heckcareoxytwit reblogged this · 1 year ago -

rosefier reblogged this · 1 year ago

rosefier reblogged this · 1 year ago -

notthenott reblogged this · 1 year ago

notthenott reblogged this · 1 year ago

More Posts from Flyingwolf29

@sellthebeamer my dear friend, I saw this and thought of you 😘

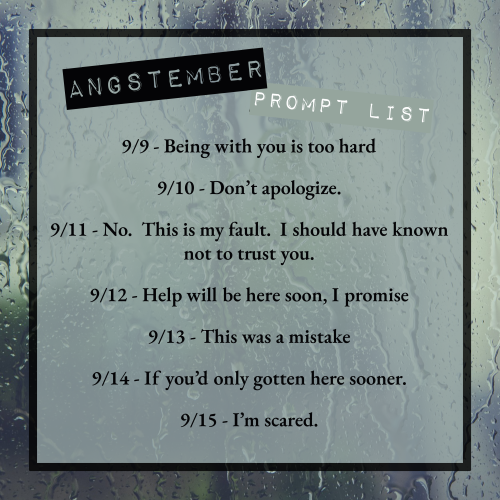

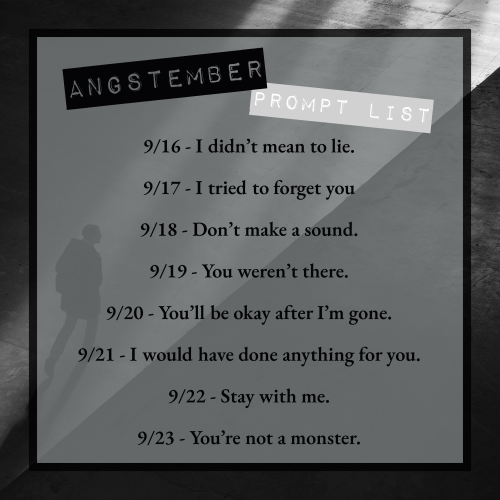

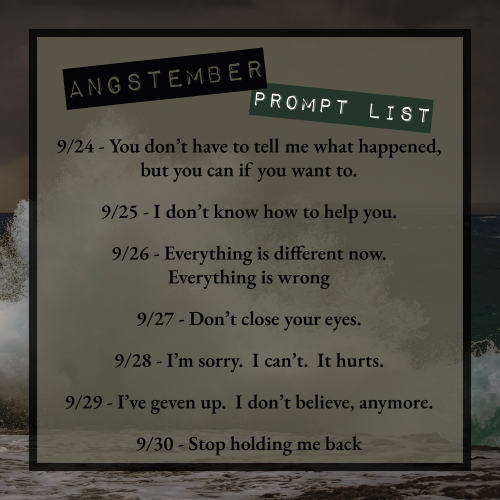

Angst!! Angst and Hurt/Comfort!!

They’re some of the most fun fanworks to both create and consume!! In the interest of inspiring some lovely, lovely angsty works, I’ve come up with a month long prompt list starting on September 1st! Welcome to Angstember!!!

This prompt list is multi-fandom, and if you’re interested in participating and sharing, please use the tag #angstember2021 (I really want to be able to see all of your stuff)!

I’ve also set up a little collection on AO3 for anyone who’d like to add their works! https://archiveofourown.org/collections/angstember_2021

I can’t wait to see all of the glorious, glorious angst that we come up with!! (also a huge thanks to @moveslikebucky for making the beautiful graphics for this event!)

I'm developing a story in my head and I'm thinking about writing it down. The thing is, I have it in my head like a tv show, each episode something new happens and it has a theme around it (It will be a detective story, each episode there is a new crime and new things revolve around it) but if I want to write it down. The chapters will be so short and it will be hard to keep up with it. Do you have any idea to basically how to turn a tv show (in my head) to a novel with decent chapters. TIA!

Turning Episodic Ideas (Like a TV Show) Into a Novel

Guide: All About Story Arcs in Television and Novels

In order to tackle this question, I think it would be helpful if we dive into the concept of “arcs” and what they mean in television vs what they mean in books. Because as much as it may seem so at times, TV dramas are almost never only episodic. Each episode ties to the rest of the episodes through various types of story arcs.

What is a Story Arc?

Story arcs are a series of events centered around a particular conflict or theme that plays out from the beginning to end of a specified time period. In TV, that time period may be an episode or a few episodes, a season, or the entire series. In books, that period may be a part/act, book, or series. Both books and television juggle these different kinds of arcs simultaneously.

Story Arcs in Television

Episode arcs are the story arcs that play out from the beginning of a TV show episode to its end. So, in a detective show, it would be whatever crime they’re solving in that episode. The crime is introduced at the beginning of the episode, investigated throughout the episode, and solved by the end of the episode.

Season arcs are the story arcs that play out from the beginning of a season to the end of the season. In many TV dramas, this conflict revolves around a “big bad” that will be defeated by the end of the season. The “big bad” is typically introduced at the end of the previous season, is battled throughout the season, and is defeated by the end of the season.

Series arcs are the story arcs that play out from the beginning of a series to the end of the series. This is the conflict at the heart of the show, that is introduced at the beginning, plays out throughout the entire series, and is resolved at the end. In speculative fiction shows like The X-Files, Once Upon a Time, or Lost, this conflict revolves around the mythology behind the story. Such as the alien conspiracy Mulder and Scully are constantly up against in The X-Files, the curses and battle between light and dark in Once Upon a Time, and the Jacob vs The Man in Black/light vs dark conflict that tie together the fates of the characters in Lost. In contemporary drama, such as family dramas or crime dramas, the series arc may be based on the overall story’s mythology (such as with This is Us or Blindspot) or it may be situation/character based, as in something like Designated Survivor.

Character arcs are the arcs that center around the internal conflict of each main character.

Story Arcs in Novels

Section arcs are conflicts that are specific to a section of the book, such as a part or an act. In a heist story, the section arc of part one might revolve around the conflict related to planning the heist and recruiting the crew. In Leigh Bardugo’s Six of Crows, for example, it was breaking Mattias Helvar out of Hellgate because they needed him for the bigger heist. Not all books have section arcs.

Story arcs are what we call the arc of the whole book/story (book one, book two, book three, etc.) that is introduced at the beginning of the book, plays out through the book, and is resolved by the end of the book.

Series arcs, in books just as in TV, are the story arcs that play out from the beginning of the series to the end of the series. In George R.R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire/Game of Thrones series, the series arc was the conflict of getting “the rightful ruler” on the Iron Throne.

Character arcs (just as in television) are the arcs that center around the internal conflict of each main character.

Turning Episodic Ideas Into a Novel

So, now that we’ve had a recap of different kinds of story arcs, we can tackle the heart of your question, which is how to turn episode-like ideas into a story with chapters.

The answer is this: you need to figure out a story arc to tie all of these “episodes” into a bigger picture, and if you want this book to be a series of books, you’ll want a series arc, too. And, whether you do a stand alone or a series, you’ll need to figure out some internal conflicts for your main characters so you can have character arcs, too.

These arcs are what take your individual “episodes” and ties them into a bigger story that spans the book from beginning to end. You could choose to make the story arc and your protagonist’s character arc one and the same if you want something more character-centric. Or, you might choose a “big bad” who is somehow behind all of the episodic conflicts, even if indirectly. You might even go with a situational conflict, like cleaning up crime in a particular part of the city and/or overthrowing a corrupt police chief.

I hope this helps!

ETA: golden-apple said: Or making it an anthology of short stories

————————————————————————————————-

Have a question? My inbox is always open, but make sure to check my FAQ and post master lists first to see if I’ve already answered a similar question. :)

stone-cold (or, confessions of a stoic)

Charlie’s always attracted danger.

Two parts his nature, one part Aunt Miranda’s stories, and one part his dad’s adventures.

Keep reading

Round Table - Next Meeting

Since there are a few days left and I am trying to become more active on this blog again (the plans are there, just the time is lacking) I thought I would share our Fanfiction Club Meetings more often.

Maybe one of you will be interested in joining us if the fic strikes their fancy :)

https://archiveofourown.org/works/778804/chapters/1465994

Fandom: SPN x SGA crossover (It's part 3, but they're mostly standalone)

Word Count: 50k

Summary: SGA/SPN Crossover AU. When an impossibly locked door is keeping the Trust from treasures unknown, they arrange to steal an Empath so that their Kinetics can ‘crack the safe’. Unfortunately for Dean, he’s the unlucky Empath and the safe is in Pegasus.

So, if you're interested we're meeting on Saturday, February 13ths at 4p.m. CET on discord (using text messages for discussions).

You're very welcome to come into my inbox or askbox to talk about it, or join us on discord if you're over 18 years old.

https://discord.gg/BPyvGcJ

So, see you on the next fictionscape! <3

A brief guide on how to punctuate dialogue

Punctuation in dialogue is one of the easiest things to get wrong in writing, and, frustratingly, it can be hard to find decent teaching resources. So if you’re struggling to tell whether to use a comma or a period, this guide is for you.

1) Every time a new character speaks, the first line of their dialogue must be set apart by a paragraph break.

Right:

“I think Jeff Bezos might be a lizard,” said Bo.

“Not this again,” I replied.

Wrong:

“I think Jeff Bezos might be a lizard,” said Bo. “Not this again,” I replied.

2) Only direct dialogue needs quotation marks. Direct dialogue is used when someone is speaking. Indirect dialogue is a summary of what was said.

Direct:

“Come on, Jeff, get ‘em!”

Indirect:

He told Jeff to go get ‘em.

3) Punctuation always goes inside quotation marks.

Right:

“What would you prefer?”

“A goat cheese salad.”

Wrong:

“What would you prefer”?

“A goat cheese salad”.

4) If you follow or start a quote with a dialogue tag, you end the quote with a comma.

Right:

“Welcome to the internet,” he said.

She asked, “Can I look around?”

Wrong:

“Welcome to the internet.” He said.

She asked. “Can I look around?”

5) But, if you follow or start a quote with an action, you use a period.

Right:

“Welcome to the internet.” He smiled.

Her eyes flicked to the screen. “Can I look around?”

Wrong:

“Welcome to the internet,” he smiled.

Her eyes flicked to the screen, “Can I look around?”

6) When breaking up dialogue with a tag, use two commas. Or, if the first piece of dialogue is a complete sentence, use a comma and then a period.

“Yes,” he replied, “an avocado.” (split sentence)

“I hoped it wouldn’t come to this,” she said. “I loved that avocado.” (full sentence)

7) You may have noticed there are two different quotation marks ( ‘ and “). And when putting a quote inside a quote, you need to use the opposite style of quotation.

Roger looked up. “And then he said, ‘I didn’t steal the avocado.’”

Or:

Roger looked up. ‘And then he said, “I didn’t steal the avocado.”’

(Using ‘ or “ often depends on personal choice. Although Brits like to use ‘ and Americans tend to use “ for their main dialogue)

So that’s my short guide to the main rules when punctuating dialogue! If you have any questions about less common rules, let me know.