Untitled And Unnamed

Untitled and Unnamed

I turn in another half done assignment, not bothering to check if my name is even on it. I might get a better grade if it’s marked missing anyways. I just can’t seem to hold onto my focus. It seems to slip out from between my fingers, and the harder I try to hold onto it, the harder it is to grasp. But there isn’t anything that I can really do about it, so I make do. Guilt and I have a very close relationship. It seems to be all I’m feeling these days. Didn’t do this assignment, didn’t do that assignment. I hardly leave my room anymore, I just wallow in my own whirlwind of thoughts and ideas that never come into focus, like a bad camera.

Everything used to come so easily to me, my attention unwavering during lessons, answers practically being whispered to me with how clear they are in my mind. I don’t know what happened. I feel like something has snapped in my brain, and now it’s like the chain fell off my bike. I pedal all I want, but I don’t make it anywhere. All I do is burn time and energy, and I gain nothing but confusion and guilt. All I feel like is that I’m getting dumber and dumber by the day, even the things that came so easily to me before are just out of my reach.

My mom says it’s just because high school is harder, but I don’t believe her. It’s the same stuff, English, history, math. It’s not that it’s harder here, it’s that I’m worse than I was. That was my limit, and it’s all downhill from here. I don't want to think that I peaked in middle school, but that’s what happened. My partner tells me that it’s not my fault, and that it’s something in my brain, but I don’t believe them. Obviously there’s something wrong with me, but blaming my incompetence on anything but myself is absurd.

Now I’m laying in my bed, staring at the ceiling, knowing that I have at least three projects that are due by the end of this week, two of which I haven’t even started yet. But it’ll be fine. They’ll get done, probably around the same time that I’m supposed to be sleeping. But four hours a night hasn’t caught up with me yet, so I can’t imagine that will change this week. I try to piece together a thought, but it just doesn’t work. It’s like my brain is full of cotton balls, and I’m struggling blindly to find the different pieces of the puzzle. I get up, and walk past the assignments I need to complete. Maybe there’s something I have to clean.

My room goes from pigsty to pristine, entirely depending on how much my mind needs to run away from the work I have to be doing. I write half of an English paper. Then delete it. I can’t turn that in. So I sit, and stare at the wall, or the floor, or the spider slowly building a web in the corner of my room. Anything but the work that makes me shake with stress. I mean, who actually cares about The Catcher in the Rye. I definitely don’t, which is why I’m using summaries and articles to tell me about the book instead of reading it. I can’t sit down and read something anymore. I used to love to read.

I feel like my identity, everything that set me apart from everyone else, that made me unique, is gone, and that I’m just blending in with everyone else again. What was my personality? Who am I? Does anyone know? I feel like I’ve lost myself, and I can’t find the person that I am supposed to be. Maybe they died in eighth grade.

Unanswered texts fill my phone notifications. I swipe them away. I don’t have the energy to talk today. 2 hours later, I pull myself from my bed, and deep clean my room for 4 hours. I don’t have the energy to do work, I tell myself as I do every chore, every task in my house. Other than the things that need to be done. I’m being so productive, getting nothing done. I’m so tired of this. I lay in my bed, midnight now, and I don’t sleep. How could I, with how many things are stuck in my head that I can’t seem to get out. I’ll do that English paper, and all three of those projects tomorrow. I’m sure I’ll have more energy tomorrow.

More Posts from Vyvie

I love these stories. They give so much inspiration

here’s a story about changelings

reposted from my old blog, which got deleted: Mary was a beautiful baby, sweet and affectionate, but by the time she’s three she’s turned difficult and strange, with fey moods and a stubborn mouth that screams and bites but never says mama. But her mother’s well-used to hard work with little thanks, and when the village gossips wag their tongues she just shrugs, and pulls her difficult child away from their precious, perfect blossoms, before the bites draw blood. Mary’s mother doesn’t drown her in a bucket of saltwater, and she doesn’t take up the silver knife the wife of the village priest leaves out for her one Sunday brunch. She gives her daughter yarn, instead, and instead of a rowan stake through her inhuman heart she gives her a child’s first loom, oak and ash. She lets her vicious, uncooperative fairy daughter entertain herself with games of her own devising, in as much peace and comfort as either of them can manage. Mary grows up strangely, as a strange child would, learning everything in all the wrong order, and biting a great deal more than she should. But she also learns to weave, and takes to it with a grand passion. Soon enough she knows more than her mother–which isn’t all that much–and is striking out into unknown territory, turning out odd new knots and weaves, patterns as complex as spiderwebs and spellrings. “Aren’t you clever,” her mother says, of her work, and leaves her to her wool and flax and whatnot. Mary’s not biting anymore, and she smiles more than she frowns, and that’s about as much, her mother figures, as anyone should hope for from their child. Mary still cries sometimes, when the other girls reject her for her strange graces, her odd slow way of talking, her restless reaching fluttering hands that have learned to spin but never to settle. The other girls call her freak, witchblood, hobgoblin. “I don’t remember girls being quite so stupid when I was that age,” her mother says, brushing Mary’s hair smooth and steady like they’ve both learned to enjoy, smooth as a skein of silk. “Time was, you knew not to insult anyone you might need to flatter later. ‘Specially when you don’t know if they’re going to grow wings or horns or whatnot. Serve ‘em all right if you ever figure out curses.” “I want to go back,” Mary says. “I want to go home, to where I came from, where there’s people like me. If I’m a fairy’s child I should be in fairyland, and no one would call me a freak.” “Aye, well, I’d miss you though,” her mother says. “And I expect there’s stupid folk everywhere, even in fairyland. Cruel folk, too. You just have to make the best of things where you are, being my child instead.” Mary learns to read well enough, in between the weaving, especially when her mother tracks down the traveling booktraders and comes home with slim, precious manuals on dyes and stains and mordants, on pigments and patterns, diagrams too arcane for her own eyes but which make her daughter’s eyes shine. “We need an herb garden,” her daughter says, hands busy, flipping from page to page, pulling on her hair, twisting in her skirt, itching for a project. “Yarrow, and madder, and woad and weld…” “Well, start digging,” her mother says. “Won’t do you a harm to get out of the house now’n then.” Mary doesn’t like dirt but she’s learned determination well enough from her mother. She digs and digs, and plants what she’s given, and the first year doesn’t turn out so well but the second’s better, and by the third a cauldron’s always simmering something over the fire, and Mary’s taking in orders from girls five years older or more, turning out vivid bolts and spools and skeins of red and gold and blue, restless fingers dancing like they’ve summoned down the rainbow. Her mother figures she probably has. “Just as well you never got the hang of curses,” she says, admiring her bright new skirts. “I like this sort of trick a lot better.” Mary smiles, rocking back and forth on her heels, fingers already fluttering to find the next project. She finally grows up tall and fair, if a bit stooped and squinty, and time and age seem to calm her unhappy mouth about as well as it does for human children. Word gets around she never lies or breaks a bargain, and if the first seems odd for a fairy’s child then the second one seems fit enough. The undyed stacks of taken orders grow taller, the dyed lots of filled orders grow brighter, the loom in the corner for Mary’s own creations grows stranger and more complex. Mary’s hands callus just like her mother’s, become as strong and tough and smooth as the oak and ash of her needles and frames, though they never fall still. “Do you ever wonder what your real daughter would be like?” the priest’s wife asks, once. Mary’s mother snorts. “She wouldn’t be worth a damn at weaving,” she says. “Lord knows I never was. No, I’ll keep what I’ve been given and thank the givers kindly. It was a fair enough trade for me. Good day, ma’am.” Mary brings her mother sweet chamomile tea, that night, and a warm shawl in all the colors of a garden, and a hairbrush. In the morning, the priest’s son comes round, with payment for his mother’s pretty new dress and a shy smile just for Mary. He thinks her hair is nice, and her hands are even nicer, vibrant in their strength and skill and endless motion. They all live happily ever after. * Here’s another story: Gregor grew fast, even for a boy, grew tall and big and healthy and began shoving his older siblings around early. He was blunt and strange and flew into rages over odd things, over the taste of his porridge or the scratch of his shirt, over the sound of rain hammering on the roof, over being touched when he didn’t expect it and sometimes even when he did. He never wore shoes if he could help it and he could tell you the number of nails in the floorboards without looking, and his favorite thing was to sit in the pantry and run his hands through the bags of dry barley and corn and oat. Considering as how he had fists like a young ox by the time he was five, his family left him to it. “He’s a changeling,” his father said to his wife, expecting an argument, but men are often the last to know anything about their children, and his wife only shrugged and nodded, like the matter was already settled, and that was that. They didn’t bind Gregor in iron and leave him in the woods for his own kind to take back. They didn’t dig him a grave and load him into it early. They worked out what made Gregor angry, in much the same way they figured out the personal constellations of emotion for each of their other sons, and when spring came, Gregor’s father taught him about sprouts, and when autumn came, Gregor’s father taught him about sheaves. Meanwhile his mother didn’t mind his quiet company around the house, the way he always knew where she’d left the kettle, or the mending, because she was forgetful and he never missed a detail. “Pity you’re not a girl, you’d never drop a stitch of knitting,” she tells Gregor, in the winter, watching him shell peas. His brothers wrestle and yell before the hearth fire, but her fairy child just works quietly, turning peas by their threes and fours into the bowl. “You know exactly how many you’ve got there, don’t you?” she says. “Six hundred and thirteen,” he says, in his quiet, precise way. His mother says “Very good,” and never says Pity you’re not human. He smiles just like one, if not for quite the same reasons. The next autumn he’s seven, a lucky number that pleases him immensely, and his father takes him along to the mill with the grain. “What you got there?” The miller asks them. “Sixty measures of Prince barley, thirty two measures of Hare’s Ear corn, and eighteen of Abernathy Blue Slate oats,” Gregor says. “Total weight is three hundred fifty pounds, or near enough. Our horse is named Madam. The wagon doesn’t have a name. I’m Gregor.” “My son,” his father says. “The changeling one.” “Bit sharper’n your others, ain’t he?” the miller says, and his father laughs. Gregor feels proud and excited and shy, and it dries up all his words, sticks them in his throat. The mill is overwhelming, but the miller is kind, and tells him the name of each and every part when he points at it, and the names of all the grain in all the bags waiting for him to get to them. “Didn’t know the fair folk were much for machinery,” the miller says. Gregor shrugs. “I like seeds,” he says, each word shelled out with careful concentration. “And names. And numbers.” “Aye, well. Suppose that’d do it. Want t’help me load up the grist?” They leave the grain with the miller, who tells Gregor’s father to bring him back ‘round when he comes to pick up the cornflour and cracked barley and rolled oats. Gregor falls asleep in the nameless wagon on the way back, and when he wakes up he goes right back to the pantry, where the rest of the seeds are left, and he runs his hands through the shifting, soothing textures and thinks about turning wheels, about windspeed and counterweights. When he’s twelve–another lucky number–he goes to live in the mill with the miller, and he never leaves, and he lives happily ever after. * Here’s another: James is a small boy who likes animals much more than people, which doesn’t bother his parents overmuch, as someone needs to watch the sheep and make the sheepdogs mind. James learns the whistles and calls along with the lambs and puppies, and by the time he’s six he’s out all day, tending to the flock. His dad gives him a knife and his mom gives him a knapsack, and the sheepdogs give him doggy kisses and the sheep don’t give him too much trouble, considering. “It’s not right for a boy to have so few complaints,” his mother says, once, when he’s about eight. “Probably ain’t right for his parents to have so few complaints about their boy, neither,” his dad says. That’s about the end of it. James’ parents aren’t very talkative, either. They live the routines of a farm, up at dawn and down by dusk, clucking softly to the chickens and calling harshly to the goats, and James grows up slow but happy. When James is eleven, he’s sent to school, because he’s going to be a man and a man should know his numbers. He gets in fights for the first time in his life, unused to peers with two legs and loud mouths and quick fists. He doesn’t like the feel of slate and chalk against his fingers, or the harsh bite of a wooden bench against his legs. He doesn’t like the rules: rules for math, rules for meals, rules for sitting down and speaking when you’re spoken to and wearing shoes all day and sitting under a low ceiling in a crowded room with no sheep or sheepdogs. Not even a puppy. But his teacher is a good woman, patient and experienced, and James isn’t the first miserable, rocking, kicking, crying lost lamb ever handed into her care. She herds the other boys away from him, when she can, and lets him sit in the corner by the door, and have a soft rag to hold his slate and chalk with, so they don’t gnaw so dryly at his fingers. James learns his numbers well enough, eventually, but he also learns with the abruptness of any lamb taking their first few steps–tottering straight into a gallop–to read. Familiar with the sort of things a strange boy needs to know, his teacher gives him myths and legends and fairytales, and steps back. James reads about Arthur and Morgana, about Hercules and Odysseus, about djinni and banshee and brownies and bargains and quests and how sometimes, something that looks human is left to try and stumble along in the humans’ world, step by uncertain step, as best they can. James never comes to enjoy writing. He learns to talk, instead, full tilt, a leaping joyous gambol, and after a time no one wants to hit him anymore. The other boys sit next to him, instead, with their mouths closed, and their hands quiet on their knees. “Let’s hear from James,” the men at the alehouse say, years later, when he’s become a man who still spends more time with sheep than anyone else, but who always comes back into town with something grand waiting for his friends on his tongue. “What’ve you got for us tonight, eh?” James finishes his pint, and stands up, and says, “Here’s a story about changelings.”

You tell me pristine is perfect.

And I'm miswriting and misinterpreting a line in a poem I don't truly understand.

But pristine isn't perfect.

Untouched (unused), unmarked (unloved).

Pristine is just that.

Pure and unsullied.

Unappreciated and unwanted.

Read my stupid stories again and then read Pristine by Hilda Raz. I'm in love with the line "You tell me the word pristine was perfect" but I don't think it has the same meaning to me as it had to her when she wrote it.

Pristine means untouched, unspoiled, or otherwise spotless. But that has never put a good feeling in my mouth. All I see when I buy something new is an item that has yet to have been loved, and after loving it, it will change into something that I have left a mark upon. The idea that pristine means perfect (I know I'm misquoting but I don't care) is so strange to me. Pristine means something that isn't cared enough about to be worn, or to be used. Like a trophy on a shelf more than an item that you genuinely value.

Anyways that's why I am very rough on shoes when I first get them. I hate it when they're all like right off the shelf and unmarked or anything.

(also I wrote a short poem about it that I will post when I get around to it)

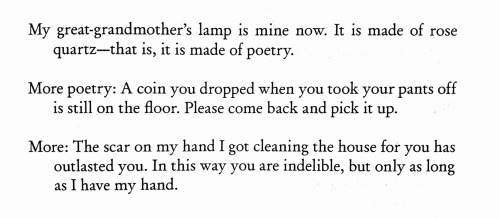

Sarah Manguso, from “Address to an Absent Lover”

A conversation about anger

“Break through,” my coworker encourages me. “You’re not angry. You’re hurt. Break through and cry.”

I don’t cry. I laugh instead because to suggest my anger is something so easily broken is ridiculous. I am molten with it, melted and reshaped all in the crucible of a trauma I can not give voice to.

“I’m just trying to help,” he says, face twisting. He hunches over the wheel and won’t meet my eyes. “You don’t have to laugh.”

“I could be angry,” I suggest and grin wider until my face feels ready to split in two. “We could have a fight.”

“Let’s talk about something else,” he says.

I think about letting him. Honestly, I do. I think about letting him change the subject to mortgages or kids or whatever else he usually likes to talk about during our long work hours. I think about the rage that I can hold back while he does it, the acid taste of resentment and hatred that’ll burn the back of my mouth as he pretends to close the can of worms he opened.

“Anger is hurt,” I say instead. I try to meet him halfway by gentling my voice and smoothing the vicious furrow of my brow. “Not all women–” I think and change the words “–not all people hold hurt the same way. I’m angry when I process these things because I’m hurt. I’m not angry to hide it.”

“Lashing out doesn’t help you,” he says. His hands are on 10 and 2 even with the rig sitting cold and dead around us. “It just keeps people away.”

“Am I lashing out?” I ask, interested.

Keep reading