how did this happen

58 posts

Vyvie - Data Was Inconclusive - Tumblr Blog

I think I could sit outside for days

Just listening to the poems in the wind,

The birdsong,

The leaves of the trees.

They say

Hear me, hear how alive I am.

The world is beautiful, and I’m experiencing it with fresh, open eyes

Do they know that I write about them?

Their lives are poetry.

I’d like that, I think,

To not not have to tell poetry through writing, but simply by being

Oh sweet birdsong,

If only I could hear what you sing about.

Then you could teach me what it is to be alive

I've been writing a lot more for this poetry class I'm in, so I think I'll publish some of those here

This is so good

So, okay, fun fact. When I was a freshman in high school… let me preface by saying my dad sent me to a private school and, like a bad organ transplant, it didn’t take. I was miserable, the student body hated me, I hated them, it was awful.

Okay, so, freshman year, I’m deep in my “everything sucks and I’m stuck with these assholes” mentality. My English teacher was a notorious hard-ass, let’s call him Mr. Hargrove. He was the guy every student prayed they didn’t get. And, on top of ALL OF THE SHIT I WAS ALREADY DEALING WITH, I had him for English.

One of the laborious assignments he gave us was to keep a daily journal. Daily! Not monthly or weekly. Fucking daily. Handwritten. And we had to turn it in every quarter and he fucking graded us. He graded us on a fucking journal.

All of my classmates wrote shit like what they did that day or whatever. But, I did not. No, sir. I decided to give the ol’ middle finger to the assignment and do my own shit.

So, for my daily journal entries, over the course of an entire year, I wrote a serialized story about a horde of man-eating slugs that invaded a small mining town. It was graphic, it was ridiculous, it was an epic feat of rebellion.

And Mr. Hargrove loved it.

It wasn’t just the journal. Every assignment he gave us, I tried to shit all over it. Every reading assignment, everyone gushed about how good it was, but I always had a negative take. Every writing assignment, people wrote boring prose, but I wrote cheesy limericks or pulp horror stories.

Then, one day, he read one of my essays to the class as an example of good writing. When a fellow student asked who wrote it, he said, “Some pipsqueak.”

And that’s when I had a revelation. He wanted to fight. And since all the other students were trying to kiss his ass, I was his only challenger.

Mr. Hargrove and I went head-to-head on every assignment, every conversation, every fucking thing. And he ate it up. And so did I.

One day, he read us a column from the Washington Post and asked the class what was wrong with it. Everyone chimed in with their dumbass takes, but I was the one who landed on Mr. Hargrove’s complaint: The reporter had BRAZENLY added the suffix “ize” to a verb.

That night I wrote a jokey letter to the reporter calling him out on the offense in which I added “ize” to every single verb. I gave it to Mr. Hargrove, who by then had become a friendly adversary, for a chuckle and he SENT IT TO THE REPORTER.

And, people… The reporter wrote back. And he said I was an exceptional student. Mr. Hargrove and I had a giggle about that because we both knew I was just being an asshole, but he and the reporter acknowledged I had a point.

And that was it. That was the moment. Not THAT EXACT moment, but that year with Mr. Hargrove taught me I had a knack for writing. And that knack was based in saying “fuck you” to authority. (The irony that someone in a position of authority helped me realize that is not lost on me.)

So, I can say without qualification that Mr. Hargrove is the reason I am now a professional writer. Yes, I do it for a living. And most of my stuff takes authorities of one kind or another to task.

Mr. Hargrove showed me my dissent was valid, my rebellion was righteous, and that killer slugs could bring a city to its knees. Someone just needs to write it.

“People say I love you all the time. When they say ‘take an umbrella, it’s raining,’ or ‘hurry back,’ or even ‘watch out, you’ll break your neck.’ There are hundreds of ways of wording it - you just have to listen for it, my dear.”

— John Patrick, The Curious Savage (via thelovejournals)

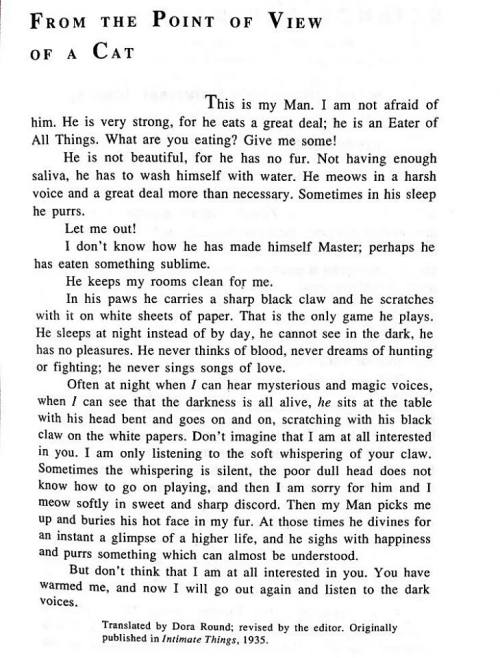

Sarah Manguso, from “Address to an Absent Lover”

I feel like I need an excuse to write. Like someone demanding a story from me

You are an anonymous professional assassin with a perfect reputation. You lead an ordinary life outside of your work. You’ve just been hired to kill yourself.

A conversation about anger

“Break through,” my coworker encourages me. “You’re not angry. You’re hurt. Break through and cry.”

I don’t cry. I laugh instead because to suggest my anger is something so easily broken is ridiculous. I am molten with it, melted and reshaped all in the crucible of a trauma I can not give voice to.

“I’m just trying to help,” he says, face twisting. He hunches over the wheel and won’t meet my eyes. “You don’t have to laugh.”

“I could be angry,” I suggest and grin wider until my face feels ready to split in two. “We could have a fight.”

“Let’s talk about something else,” he says.

I think about letting him. Honestly, I do. I think about letting him change the subject to mortgages or kids or whatever else he usually likes to talk about during our long work hours. I think about the rage that I can hold back while he does it, the acid taste of resentment and hatred that’ll burn the back of my mouth as he pretends to close the can of worms he opened.

“Anger is hurt,” I say instead. I try to meet him halfway by gentling my voice and smoothing the vicious furrow of my brow. “Not all women–” I think and change the words “–not all people hold hurt the same way. I’m angry when I process these things because I’m hurt. I’m not angry to hide it.”

“Lashing out doesn’t help you,” he says. His hands are on 10 and 2 even with the rig sitting cold and dead around us. “It just keeps people away.”

“Am I lashing out?” I ask, interested.

Keep reading

Fate and Mercy and Dead Girls

Summary: Sometimes, when things go very wrong, the Chosen One gets a wish. That’s where Danielle comes in. (Tagged with Blood, violence, child death)

————–

Danielle is cursed.

This battlefield is nice. It’s early afternoon and the breeze that comes from the forest to the east is sweet. The fighting has only just begun and the scent of blood is still hovering at the edge of her senses. It hasn’t erased the taste of the dead girl’s last meal – bread sweetened with honey – yet. She’s used to storm clouds the size of mountains roiling overhead, the electric sting of lightning against her skin, the crash of blades against armor and arrows against shields. The sun is warm and honey-sweet against her cheek and there’s no fighting going on right now. There’s only the low murmur of voices from all around and some muffled sobbing.

If she weren’t waking up in the body of a dead girl, she’d call it picnic weather.

Time to pay attention.

“—Chosen One is dead,” a man says. His voice matches the weather more than the situation. Calm. Even. Gentle. A wave lapping at the shore before the tsunami. She can feel his aura undulating through the ground, dark and demanding. Demon King? Mad Emperor? Dark Lord? One of those types. He projects his words over the renewed sobbing. “Do you see your folly now, honorable knights? The wasted months of defiance? You were never going to defeat my army even with years and seven fabled soldiers at your mercy rather than the one. Here, the day of your final rebellion, your Hero lies dead after only one volley.”

Hero. Danielle is cursed, she shouldn’t be feeling pity for anyone but herself. But there it is, the familiar bile in the back of her throat, the prickling of her eyes, the tightening in her chest. This dead girl was their Hero. They made her their Chosen One. From the feel of it, they didn’t school in her magic or train her in swordsmanship. Her muscles are burning from death, yes, but also from overexertion.

What do you want? Danielle asks. All of the right systems are under her control now. The ground is cold against her back, the girl’s tiny curls a tickle against her face. The air is sweet underneath the scent of a dying blow and she can hear the conversations around her clearly. The Dark Lord is still gloating, giving the knights their time to mourn and his own forces time to ready the next attack. Sweetheart, what do you want?

The girl’s soul shudders. I-I’m not dead?

Keep reading

Sweet Music

It was a dark and stormy night, because that’s how these kinds of stories are supposed to start, and the forest was alive. If you were there, you wouldn’t see much, maybe a few shadows that seem a bit long, and did that bush just move? In this situation, you might start to feel a measure of panic start to form. Thankfully, you’re not there, and the denizens of the forest have no desire to harm you or anyone else. The harvest moon was bright in the sky, shining a golden light down through the vines and branches, and the things of the forest were celebrating.

Contrary to popular human belief, there are still plenty of wild places in the world, and their fairy tales weren’t the constructs of an overeager imagination. The fair folk, the monsters, all of the good, and all of the bad. But tonight isn’t the time to talk about such topics, because tonight is a night to make merry, and enjoy life. Even the trees seem to be reaching to the sky, ready to pluck the moon right from the stars. Not a soul in this forest rests tonight, wicked or pure. Tonight represents a new beginning, a rebirth of sorts. There is one of them, barely a whisper of a thought, a newborn god, weak in its youth, and loved by all.

For five months, it lives, slowly withering away into nothing more than a flicker of smoke. The forest feels the loss, and lays silent for a time. But after their month of mourning, the harvest moon rises once more, and its light shines on the beloved one, birthing it anew, stronger each time. The presence isn’t a very strong one, and it is not feared. How could something so seemingly unimportant evoke such feelings from all of the forest? How could it possibly be something worth noticing? Most humans have looked past it and decided it was not important, leaving it behind for someone else to care for. The forgotten and strange decided that it was theirs, and so they took it in.

It saw so much in the world, finding beauty in every crevice. No creature was too vile, no patch of darkness too deep. It cared for them all and looked upon them with nothing but love and adoration. The forest kept it. They were left behind for a reason, they were abandoned by all of the rest of the world, not fitting the standards of the mundane. But this… this feeling of being loved and respected, it was like a drug to them, they couldn’t get enough. And so they mourn its death, and celebrate its rebirth.

When it lives, it enjoys life, and all that it offers. It dances to birdsong in the early morning, twirling and leaping to the shrill tweets. It would sing along, but its voice would overpower the birds so that it would not be able to hear their music. It glides over streams, swooping through the water to look at the fish, and back out again. There is not an inch of the world that it does not care for, and it makes it known to all.

Such a being is so incredible, and so unbelievably good. Even just being around something like it makes everything seem better, brightening the world as you take it in, your own personal pair of rose colored glasses, painting the world in pink. It appreciates all of the things humanity does not, singing to the things we find creepy or unappealing, dancing with the monsters under our bed, finding beauty in them despite how we find them dreadful.

It is not limited to the scope of humanity, however, and it finds beauty in things that we cannot even see. It looks to the sky, not just to see the clouds, but to watch the wonderful swirls and eddies of the wind, moving akin to flowing water. Though it is not limited by the pull of gravity, it loves the way that the world holds itself, tying it all together with one large pulling force. Deep underground, it watches the very crust of the earth push and pull over time, rigid but still flowing. Deeper still, the very core of the Earth. If anything was to be blamed for life, it would be that. A small barrier of protection, to carefully nurture creation. It loves all of it, it loves every little thing, and a little bit of it is in everyone, some more than others.

Now, I know you likely don’t believe me, but that’s not why I write this. I tell you all of this because the world is full of beauty, and you can pick and choose what to love, or you can decide to love everything, for their blessings and their flaws. When you look at something and love it, so much that it feels like your entirety focuses on that one thing, that presence is there, watching with you, just as entranced.

Dance to music that you love, sit and stare at something wonderful, stare into the stars and sing the beautiful music that your soul makes into them. Every part of everything has something to like. You can even find the good in the sad. Sadness and depression are unpleasant feelings, but you can still try your hardest to find joy in things, even when there is a lack of it in you.

The strum of a guitar, the beating heart of a bass drum, the swooping soft sound of a singer. Find what brings you the most happiness, and do it without self depreciation. There is no shame in loving something, even if others don’t agree with it.

Bring joy to the ones who need it, and love the ones who need love. It’s so easy to be good to others.

I love these stories. They give so much inspiration

here’s a story about changelings

reposted from my old blog, which got deleted: Mary was a beautiful baby, sweet and affectionate, but by the time she’s three she’s turned difficult and strange, with fey moods and a stubborn mouth that screams and bites but never says mama. But her mother’s well-used to hard work with little thanks, and when the village gossips wag their tongues she just shrugs, and pulls her difficult child away from their precious, perfect blossoms, before the bites draw blood. Mary’s mother doesn’t drown her in a bucket of saltwater, and she doesn’t take up the silver knife the wife of the village priest leaves out for her one Sunday brunch. She gives her daughter yarn, instead, and instead of a rowan stake through her inhuman heart she gives her a child’s first loom, oak and ash. She lets her vicious, uncooperative fairy daughter entertain herself with games of her own devising, in as much peace and comfort as either of them can manage. Mary grows up strangely, as a strange child would, learning everything in all the wrong order, and biting a great deal more than she should. But she also learns to weave, and takes to it with a grand passion. Soon enough she knows more than her mother–which isn’t all that much–and is striking out into unknown territory, turning out odd new knots and weaves, patterns as complex as spiderwebs and spellrings. “Aren’t you clever,” her mother says, of her work, and leaves her to her wool and flax and whatnot. Mary’s not biting anymore, and she smiles more than she frowns, and that’s about as much, her mother figures, as anyone should hope for from their child. Mary still cries sometimes, when the other girls reject her for her strange graces, her odd slow way of talking, her restless reaching fluttering hands that have learned to spin but never to settle. The other girls call her freak, witchblood, hobgoblin. “I don’t remember girls being quite so stupid when I was that age,” her mother says, brushing Mary’s hair smooth and steady like they’ve both learned to enjoy, smooth as a skein of silk. “Time was, you knew not to insult anyone you might need to flatter later. ‘Specially when you don’t know if they’re going to grow wings or horns or whatnot. Serve ‘em all right if you ever figure out curses.” “I want to go back,” Mary says. “I want to go home, to where I came from, where there’s people like me. If I’m a fairy’s child I should be in fairyland, and no one would call me a freak.” “Aye, well, I’d miss you though,” her mother says. “And I expect there’s stupid folk everywhere, even in fairyland. Cruel folk, too. You just have to make the best of things where you are, being my child instead.” Mary learns to read well enough, in between the weaving, especially when her mother tracks down the traveling booktraders and comes home with slim, precious manuals on dyes and stains and mordants, on pigments and patterns, diagrams too arcane for her own eyes but which make her daughter’s eyes shine. “We need an herb garden,” her daughter says, hands busy, flipping from page to page, pulling on her hair, twisting in her skirt, itching for a project. “Yarrow, and madder, and woad and weld…” “Well, start digging,” her mother says. “Won’t do you a harm to get out of the house now’n then.” Mary doesn’t like dirt but she’s learned determination well enough from her mother. She digs and digs, and plants what she’s given, and the first year doesn’t turn out so well but the second’s better, and by the third a cauldron’s always simmering something over the fire, and Mary’s taking in orders from girls five years older or more, turning out vivid bolts and spools and skeins of red and gold and blue, restless fingers dancing like they’ve summoned down the rainbow. Her mother figures she probably has. “Just as well you never got the hang of curses,” she says, admiring her bright new skirts. “I like this sort of trick a lot better.” Mary smiles, rocking back and forth on her heels, fingers already fluttering to find the next project. She finally grows up tall and fair, if a bit stooped and squinty, and time and age seem to calm her unhappy mouth about as well as it does for human children. Word gets around she never lies or breaks a bargain, and if the first seems odd for a fairy’s child then the second one seems fit enough. The undyed stacks of taken orders grow taller, the dyed lots of filled orders grow brighter, the loom in the corner for Mary’s own creations grows stranger and more complex. Mary’s hands callus just like her mother’s, become as strong and tough and smooth as the oak and ash of her needles and frames, though they never fall still. “Do you ever wonder what your real daughter would be like?” the priest’s wife asks, once. Mary’s mother snorts. “She wouldn’t be worth a damn at weaving,” she says. “Lord knows I never was. No, I’ll keep what I’ve been given and thank the givers kindly. It was a fair enough trade for me. Good day, ma’am.” Mary brings her mother sweet chamomile tea, that night, and a warm shawl in all the colors of a garden, and a hairbrush. In the morning, the priest’s son comes round, with payment for his mother’s pretty new dress and a shy smile just for Mary. He thinks her hair is nice, and her hands are even nicer, vibrant in their strength and skill and endless motion. They all live happily ever after. * Here’s another story: Gregor grew fast, even for a boy, grew tall and big and healthy and began shoving his older siblings around early. He was blunt and strange and flew into rages over odd things, over the taste of his porridge or the scratch of his shirt, over the sound of rain hammering on the roof, over being touched when he didn’t expect it and sometimes even when he did. He never wore shoes if he could help it and he could tell you the number of nails in the floorboards without looking, and his favorite thing was to sit in the pantry and run his hands through the bags of dry barley and corn and oat. Considering as how he had fists like a young ox by the time he was five, his family left him to it. “He’s a changeling,” his father said to his wife, expecting an argument, but men are often the last to know anything about their children, and his wife only shrugged and nodded, like the matter was already settled, and that was that. They didn’t bind Gregor in iron and leave him in the woods for his own kind to take back. They didn’t dig him a grave and load him into it early. They worked out what made Gregor angry, in much the same way they figured out the personal constellations of emotion for each of their other sons, and when spring came, Gregor’s father taught him about sprouts, and when autumn came, Gregor’s father taught him about sheaves. Meanwhile his mother didn’t mind his quiet company around the house, the way he always knew where she’d left the kettle, or the mending, because she was forgetful and he never missed a detail. “Pity you’re not a girl, you’d never drop a stitch of knitting,” she tells Gregor, in the winter, watching him shell peas. His brothers wrestle and yell before the hearth fire, but her fairy child just works quietly, turning peas by their threes and fours into the bowl. “You know exactly how many you’ve got there, don’t you?” she says. “Six hundred and thirteen,” he says, in his quiet, precise way. His mother says “Very good,” and never says Pity you’re not human. He smiles just like one, if not for quite the same reasons. The next autumn he’s seven, a lucky number that pleases him immensely, and his father takes him along to the mill with the grain. “What you got there?” The miller asks them. “Sixty measures of Prince barley, thirty two measures of Hare’s Ear corn, and eighteen of Abernathy Blue Slate oats,” Gregor says. “Total weight is three hundred fifty pounds, or near enough. Our horse is named Madam. The wagon doesn’t have a name. I’m Gregor.” “My son,” his father says. “The changeling one.” “Bit sharper’n your others, ain’t he?” the miller says, and his father laughs. Gregor feels proud and excited and shy, and it dries up all his words, sticks them in his throat. The mill is overwhelming, but the miller is kind, and tells him the name of each and every part when he points at it, and the names of all the grain in all the bags waiting for him to get to them. “Didn’t know the fair folk were much for machinery,” the miller says. Gregor shrugs. “I like seeds,” he says, each word shelled out with careful concentration. “And names. And numbers.” “Aye, well. Suppose that’d do it. Want t’help me load up the grist?” They leave the grain with the miller, who tells Gregor’s father to bring him back ‘round when he comes to pick up the cornflour and cracked barley and rolled oats. Gregor falls asleep in the nameless wagon on the way back, and when he wakes up he goes right back to the pantry, where the rest of the seeds are left, and he runs his hands through the shifting, soothing textures and thinks about turning wheels, about windspeed and counterweights. When he’s twelve–another lucky number–he goes to live in the mill with the miller, and he never leaves, and he lives happily ever after. * Here’s another: James is a small boy who likes animals much more than people, which doesn’t bother his parents overmuch, as someone needs to watch the sheep and make the sheepdogs mind. James learns the whistles and calls along with the lambs and puppies, and by the time he’s six he’s out all day, tending to the flock. His dad gives him a knife and his mom gives him a knapsack, and the sheepdogs give him doggy kisses and the sheep don’t give him too much trouble, considering. “It’s not right for a boy to have so few complaints,” his mother says, once, when he’s about eight. “Probably ain’t right for his parents to have so few complaints about their boy, neither,” his dad says. That’s about the end of it. James’ parents aren’t very talkative, either. They live the routines of a farm, up at dawn and down by dusk, clucking softly to the chickens and calling harshly to the goats, and James grows up slow but happy. When James is eleven, he’s sent to school, because he’s going to be a man and a man should know his numbers. He gets in fights for the first time in his life, unused to peers with two legs and loud mouths and quick fists. He doesn’t like the feel of slate and chalk against his fingers, or the harsh bite of a wooden bench against his legs. He doesn’t like the rules: rules for math, rules for meals, rules for sitting down and speaking when you’re spoken to and wearing shoes all day and sitting under a low ceiling in a crowded room with no sheep or sheepdogs. Not even a puppy. But his teacher is a good woman, patient and experienced, and James isn’t the first miserable, rocking, kicking, crying lost lamb ever handed into her care. She herds the other boys away from him, when she can, and lets him sit in the corner by the door, and have a soft rag to hold his slate and chalk with, so they don’t gnaw so dryly at his fingers. James learns his numbers well enough, eventually, but he also learns with the abruptness of any lamb taking their first few steps–tottering straight into a gallop–to read. Familiar with the sort of things a strange boy needs to know, his teacher gives him myths and legends and fairytales, and steps back. James reads about Arthur and Morgana, about Hercules and Odysseus, about djinni and banshee and brownies and bargains and quests and how sometimes, something that looks human is left to try and stumble along in the humans’ world, step by uncertain step, as best they can. James never comes to enjoy writing. He learns to talk, instead, full tilt, a leaping joyous gambol, and after a time no one wants to hit him anymore. The other boys sit next to him, instead, with their mouths closed, and their hands quiet on their knees. “Let’s hear from James,” the men at the alehouse say, years later, when he’s become a man who still spends more time with sheep than anyone else, but who always comes back into town with something grand waiting for his friends on his tongue. “What’ve you got for us tonight, eh?” James finishes his pint, and stands up, and says, “Here’s a story about changelings.”

nobody tears through library books quite as fast as a 12 yr old girl with no friends

You tell me pristine is perfect.

And I'm miswriting and misinterpreting a line in a poem I don't truly understand.

But pristine isn't perfect.

Untouched (unused), unmarked (unloved).

Pristine is just that.

Pure and unsullied.

Unappreciated and unwanted.

Read my stupid stories again and then read Pristine by Hilda Raz. I'm in love with the line "You tell me the word pristine was perfect" but I don't think it has the same meaning to me as it had to her when she wrote it.

Pristine means untouched, unspoiled, or otherwise spotless. But that has never put a good feeling in my mouth. All I see when I buy something new is an item that has yet to have been loved, and after loving it, it will change into something that I have left a mark upon. The idea that pristine means perfect (I know I'm misquoting but I don't care) is so strange to me. Pristine means something that isn't cared enough about to be worn, or to be used. Like a trophy on a shelf more than an item that you genuinely value.

Anyways that's why I am very rough on shoes when I first get them. I hate it when they're all like right off the shelf and unmarked or anything.

(also I wrote a short poem about it that I will post when I get around to it)

Read my stupid stories again and then read Pristine by Hilda Raz. I'm in love with the line "You tell me the word pristine was perfect" but I don't think it has the same meaning to me as it had to her when she wrote it.

Pristine means untouched, unspoiled, or otherwise spotless. But that has never put a good feeling in my mouth. All I see when I buy something new is an item that has yet to have been loved, and after loving it, it will change into something that I have left a mark upon. The idea that pristine means perfect (I know I'm misquoting but I don't care) is so strange to me. Pristine means something that isn't cared enough about to be worn, or to be used. Like a trophy on a shelf more than an item that you genuinely value.

Anyways that's why I am very rough on shoes when I first get them. I hate it when they're all like right off the shelf and unmarked or anything.

(also I wrote a short poem about it that I will post when I get around to it)

it seems so strange to me that the only people it is socially acceptable to live with (once you reach a certain stage in life) are sexual partners? like why can’t i live with my best friend? why can’t i raise a child with them? why do i need to have sex with someone in order to live with them? why do we put certain relationships on a pedestal? why don’t we value non-sexual relationships enough? why do life partners always have to be sexual partners?

i wanna do that but with my teeth

dandelions are magic. literally tiny suns in the grass that turn into the moon and then the stars when you blow on them. fucking insane.

Absolutely amazing

Hey if u like the ocean look at this its rly cool I think

Untitled and Unnamed

I turn in another half done assignment, not bothering to check if my name is even on it. I might get a better grade if it’s marked missing anyways. I just can’t seem to hold onto my focus. It seems to slip out from between my fingers, and the harder I try to hold onto it, the harder it is to grasp. But there isn’t anything that I can really do about it, so I make do. Guilt and I have a very close relationship. It seems to be all I’m feeling these days. Didn’t do this assignment, didn’t do that assignment. I hardly leave my room anymore, I just wallow in my own whirlwind of thoughts and ideas that never come into focus, like a bad camera.

Everything used to come so easily to me, my attention unwavering during lessons, answers practically being whispered to me with how clear they are in my mind. I don’t know what happened. I feel like something has snapped in my brain, and now it’s like the chain fell off my bike. I pedal all I want, but I don’t make it anywhere. All I do is burn time and energy, and I gain nothing but confusion and guilt. All I feel like is that I’m getting dumber and dumber by the day, even the things that came so easily to me before are just out of my reach.

My mom says it’s just because high school is harder, but I don’t believe her. It’s the same stuff, English, history, math. It’s not that it’s harder here, it’s that I’m worse than I was. That was my limit, and it’s all downhill from here. I don't want to think that I peaked in middle school, but that’s what happened. My partner tells me that it’s not my fault, and that it’s something in my brain, but I don’t believe them. Obviously there’s something wrong with me, but blaming my incompetence on anything but myself is absurd.

Now I’m laying in my bed, staring at the ceiling, knowing that I have at least three projects that are due by the end of this week, two of which I haven’t even started yet. But it’ll be fine. They’ll get done, probably around the same time that I’m supposed to be sleeping. But four hours a night hasn’t caught up with me yet, so I can’t imagine that will change this week. I try to piece together a thought, but it just doesn’t work. It’s like my brain is full of cotton balls, and I’m struggling blindly to find the different pieces of the puzzle. I get up, and walk past the assignments I need to complete. Maybe there’s something I have to clean.

My room goes from pigsty to pristine, entirely depending on how much my mind needs to run away from the work I have to be doing. I write half of an English paper. Then delete it. I can’t turn that in. So I sit, and stare at the wall, or the floor, or the spider slowly building a web in the corner of my room. Anything but the work that makes me shake with stress. I mean, who actually cares about The Catcher in the Rye. I definitely don’t, which is why I’m using summaries and articles to tell me about the book instead of reading it. I can’t sit down and read something anymore. I used to love to read.

I feel like my identity, everything that set me apart from everyone else, that made me unique, is gone, and that I’m just blending in with everyone else again. What was my personality? Who am I? Does anyone know? I feel like I’ve lost myself, and I can’t find the person that I am supposed to be. Maybe they died in eighth grade.

Unanswered texts fill my phone notifications. I swipe them away. I don’t have the energy to talk today. 2 hours later, I pull myself from my bed, and deep clean my room for 4 hours. I don’t have the energy to do work, I tell myself as I do every chore, every task in my house. Other than the things that need to be done. I’m being so productive, getting nothing done. I’m so tired of this. I lay in my bed, midnight now, and I don’t sleep. How could I, with how many things are stuck in my head that I can’t seem to get out. I’ll do that English paper, and all three of those projects tomorrow. I’m sure I’ll have more energy tomorrow.

The Most Beautiful, and Most Clever

Cinderella was the daughter of a rich man, which gave her quite good standing in society. She learned all the polite and nice things that a girl of her position would learn, like which fork to use when eating different foods, and how to fake a laugh when a social situation calls for it. She was a perfect lady, when one looked only at her outward appearance. But inside she was secretly a very rotten and selfish girl. She wanted a flawless life, riches, and pretty things. So when her mother died, she wasn’t heartbroken, as she did not care for her as a loving daughter should, and simply continued plotting her perfect life.

Her father, like all men with money during this time, became lonely, and eventually married again. The woman he married was very plain, without a hint of interesting personality, and she had two daughters. These daughters took after their mother, in that they were perfectly average ladies. There was no spark of ambition in them. One day Cinderella had an idea, a perfect idea. She went out into the city, no one in her family willing to question her. As she walked, dozens of boys tried to get her attention, but she paid them no mind. They were nothing, no social standing, no worth.

Eventually, she found what she was looking for, a dark tent in the corner of the never-ending market in the beating heart of the city. She walked inside, with the arrogance of someone who was sure of every step she took. The inside of the tent seemed almost bigger than the outside, and there were shelves upon shelves of what looked like useless trinkets. She ignored them completely and approached the bent-backed crone towards the back.

The crone looked up, and croaked, “What is it that you desire, fine lady?”

Cinderella, impatiently, said, “I desire everything, I want the world at my fingertips.”

The crone cackled with delight, as she pulled out a small bag, “Take these, and plant them in your garden. With them, you will have all that you desire.” Cinderella took the bag, and without a glace back, left the tent, and the market. As she arrived back at her home, she immediately went behind the house, to the stretch of green grass and colorful flowers. She knelt down in the dirt with disgust, and opened the bag, flinching as she saw what was inside. As she lifted the first (presumably human) eyeball from the bag, she set it inside a small hole in the dirt she had created with a small shovel. After planting the remaining 3 eyes, she went back inside, and went to sleep.

The next day, she checked on them, with no changes. This repeated for a week, no change whatsoever. Feeling cheated, she tried to go back to the crone’s tent, but found that it was gone, along with every strange thing inside. Furious that she had been deceived, she went back to the buried eyes, and furiously tried to dig them back out with her hands, shovel forgotten. Her fingernail caught on a rock in the soil, breaking, and she cried out. She pulled her hand away from the soil immediately, and saw the blood staining her finger, as well as the ground beneath. Tears welling in the corner of her eyes, from anger or pain, she did not know, she went back inside to clean the blood and dirt from her hands.

As she calmed down, her blood cooling in her veins, she went back outside to finish the job with the forgotten shovel. She nearly dropped it in surprise, as a twisted, blackened tree stood where there had been nothing before, right over where her blood had fallen. Still unhappy, she walked to the base of the now towering tree, nearly three times her height, and put her hand against the trunk. How was this supposed to give her what she wanted? In her anger and frustration, she shouted out, “I wish people would simply give me anything I could want for! Why can nothing be as simple as I want it to be?” Suddenly, the wind started to pick up, and the branches started creaking, creating a discord of screeching wood. Then, as quickly as it came, the wind died down, and the tree fell silent.

She walked back into her house, and was greeted by her father, who smiled at her lovingly. She despised it. She didn’t need his love, didn’t want it. He couldn’t give her what she truly seeked, power, and admiration from all. Suddenly, as if hearing the very thoughts in her head, he turned and immediately walked out of the room. Strange.

As the sun began to lower along the horizon, she had dinner with her family, a usually dreadful task, with all of them trying to converse with her, believing her to be their friend. But tonight, there was nothing. Complete silence. They all still came, and still ate, but there was not a word of conversation directed towards her. It was like paradise, and she began to wonder if that wretched tree did its job after all. Now that she knew it worked, she began putting her plans into motion. She had heard about a prince, some highborn boy, who lived in a nearby city, and who had finally allowed his father to see him wed. But with one condition, that he would have three large dances, and that he would pick his bride from whosoever caught his heart. The king, happy to give his son all that he asks for, agreed.

Cinderella may have been incredibly intelligent, but she was also prideful. She did not think she had to use her powers to seduce one boy. Afterall, she was perfectly beautiful, and perfectly elegant. So she went to the party, dressed in the most dazzling dress she owned, and began to attempt to gain his attention. But for some reason, the prince never even looked at her, dancing with all, from the peasants to the giggling ladies, but never her. She was enraged, but knew she could still succeed. Clearly, this dress was not enough, she needed to look more amazing, look like a queen. So that night, after the first dance was over, she went back to the gnarled tree in shame.

“I wish for a dress that outshines all others, a true work of art.” And as the wind picked up, she beheld a silver dress, like the shine of the stars captured into fabric, hanging from one of the twisted branches. As she grabbed it greedily, and went back inside, she began to talk to herself. “Now he cannot miss me, and I will be the only thing he can look at.” And the next day, she went. But the same as the last day, the prince danced with many, of high and low standing, and the same as the last day, spared her not a glance. She stormed out of the dance once more, going back to the tree, and demanding an even more astounding dress, one that no one could look at and ignore. And as the tree gifted her another dress, deep colored gemstones shining across it, she went back inside once more.

Tonight, the final dance, she knew it would be the one. She walked in, all eyes on her, confident in her excellence. She walked directly up to the prince, staring him in the eyes. But he seemed to glance past her, eyes unfocused, and simply walked by. Shaking with fury, embarrassed beyond belief, she ran home, to the wishing tree. She asked to know why, why did he act as though she simply wasn’t there. And the tree, not gifted with speech, simply showed her, as that wind picked up once more, and she was pulled towards the tree, trapping her against it.

The creeping branches moved closer to her face, until they crawled into her eyes, ripping them out, as payment. As she heard a cackle, seeing nothing but darkness, she screamed, in anger, frustration, and in terrible, horrible pain and understanding. For the tree had given her what she asked, had told her why she went unnoticed, why she now kneeled here, seeing nothing. She was filled with shame and painful regret. The prince, whom she tried to seduce with her appearance alone, was blind. She lived the rest of her life without sight, and with none seeing her beauty, past her empty sockets. All they saw was her rotten, worm riddled soul.