Fukuchi Genichirou - Tumblr Posts

@pompompurin1028 here is what I discovered about Fukuchi Gen'chirou last night HAHA it's quite long so I decided to dedicate a post for it

thoughts on the life of Fukuchi Gen'ichirou/Ouchi

Below the cut is a half-essay half-ramble about the biography of one of Meiji Japan's pioneers. A lot of it consists of comparisons with Fukuzawa Yukichi, another famous intellectual of the day, and of course, their BSD counterparts. If you're curious as to where I got this information, I'll be posting the sources in the replies of this post

notes: contains MAJOR spoilers for BSD S4 and the manga!

Fukuchi Gen'ichirou (1841-1906), penname Fukuchi Ouchi was, like his better-known contemporary Fukuzawa Yukichi (1835-1901), one of the leading advocates for modernization of Meiji-era Japan. Both were men of many talents that dabbled in several fields such as diplomacy and politics, but Fukuchi is most recognized for his contributions as a journalist and editor of the Tokyo Nichi Nichi (Tokyo Daily), earning him the title “Father of the Modern Japanese Press.”

A young Fukuchi was in high pursuit of the Western ideal. He grew up under the Tokugawa shogunate and studied what children of his time were made to learn: memorization of Confucian classics, calligraphy, and Chinese literature. As such, it was no surprise that it was his instinct to nearly reject all forms of Japanese tradition once he began his Dutch studies (rangaku) and even went so far as to leave his hometown to continue his studies in the capital, Edo. After learning Dutch and English, he worked as an interpreter for the shogunate - a path many scholars then would frown upon. This is not unlike Fukuzawa’s own beginnings, I must add.

[I would like to note that during the isolationist Edo period of Japan, the only access they had to Western goods and thought were through the Dutch: the only Westerners they traded with. However by the 1850s, even the most well-studied Japanese in rangaku would have fallen behind as most of the advancements, brought about by the arrival of the Americans, would have required the knowledge of English.]

As the years passed, however, what used to bring him such euphoria then began to wear him down. Interacting with these Westerners whom he so idolized only to be met with insensitive and tyrannical people sparked Fukuchi’s disillusionment. For example, merchants were considered to be one of the lowest classes in Tokugawa Japan, yet these Western merchants acted as if they were in the same league as the emperor. In his own words: “They made us furious. They were proud, rude, antagonizing barbarians.”

This would bring Fukuchi to some sort of blend between Eastern and Western thought. The goal was, as it had always been, the strengthening and modernization of Japan, but that did not require a total upheaval of their traditional values. Only a selection of Western methods would work. This may seem like a reasonable compromise (as a similar strain of logic could be found in Fukuzawa’s own writing), but as we shall see later this blend is not as harmonious as it seems.

When the shogunate was overthrown by the Meiji government in 1868, Fukuchi established a newspaper (a “modern-style” one at that) to defend the Tokugawa family and to criticize the new government. This would be the beginning of his career as one of the foremost journalists and critics of the time. He believed that:

"If I were to take up writing with the brush, using the newspaper as my medium I might eventually see my ideas realized in society."

Now let’s discuss: “what tf is a modern-style newspaper?”

Up to the early Meiji period, newspapers were viewed as “low forms of entertainment” that educated men of high class should not bother thinking about. Political editorials were superior to “news” as the latter usually compromised what we’d consider as gossip. Fukuchi, still bred in Western thought, had a different idea: objective news reporting is just as valid as political write-ups. As he said,

“Newspapers are the eyes and ears of the world, the movers of mankind”

There are two types of staff for these newspapers: the “real writers,” those who wrote political editorials, and the illiterate “news” gatherers. In his newspaper Fukuchi made even the former type to go on the hunt for “real news,” and because of this and the coverage of the 1877 Satsuma Rebellion, he is considered to be one of the first war correspondents (which is, btw, one of Kunikida’s early jobs. just had to plug that in sorry HAHA. it’s a good enough job tho, that’s my point).

But this did not mean that he viewed the two forms as equal. The front page was still dedicated to commentaries and opinions rather than plain news. This may be attributed to the fact that “he was reared in a country and era where public service was defined not in terms of aiding society, but of assisting the bureaucracy of government.” His editorials were sharp and bold, despite the new laws restricting press freedom, criticizing the current Meiji government and advocating for a parliamentary government and international trade. Like many other critics such as Suehiro Tetchou, he would end up in jail for some time.

Being a journalist and editor gave him a voice and eventually political influence and power. As Fukuchi would repeat over and over again,

"If one cannot become prime minister one should become a journalist."

He would join and become president of the first prefectural assembly in 1879, the same one Fukuzawa joined but left only a year later to focus on “the need to develop an independent intelligentsia,” such as managing the school he founded (which would later become Keio University). Perhaps he had sensed that this political body would do essentially nothing - one thing that Fukuchi did not or perhaps refuse to recognize. He felt that this assembly, as well as the conservative party he founded in 1882, were the “right” balance of Eastern ethics and Western methods he had so dreamed of.

Huffman and Brown have noted in their writings that Fukuchi’s personality was “less than admirable.” I’d like to believe that this is one of the main driving factors for the philosophies he’d held in his life; it just fits so perfectly. For one, his sense of fashion was close to that of a Western dandy (see pic below) but the customs he preferred were very Japanese (tea, architecture).

Fig. 1 Fukuchi in his old age (left) and a woodblock print of him in Kyushu 1873 (right)

Huffman notes that this may not strike one as strange, but the symbolisms are very much clashing. He’d also “strut openly with geisha, throwing money away,” according to Mori Ougai, despite his conviction in being a “high class man.” Another contradictory trait of Fukuchi’s is his penchant for criticizing officials for having their favorites, yet he has his own “feudal” tendencies and maintained his inability to be “objective and cool-headed.” As his friend and Fukuzawa’s rival Itou Hirobumi said,

“If you would just quit acting so much like a loyal retainer, Fukuchi, you might be named to a post like foreign minister!”

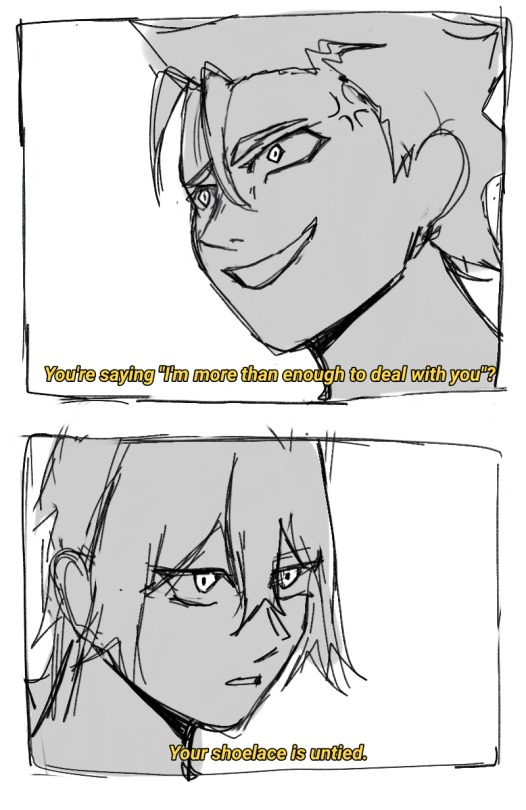

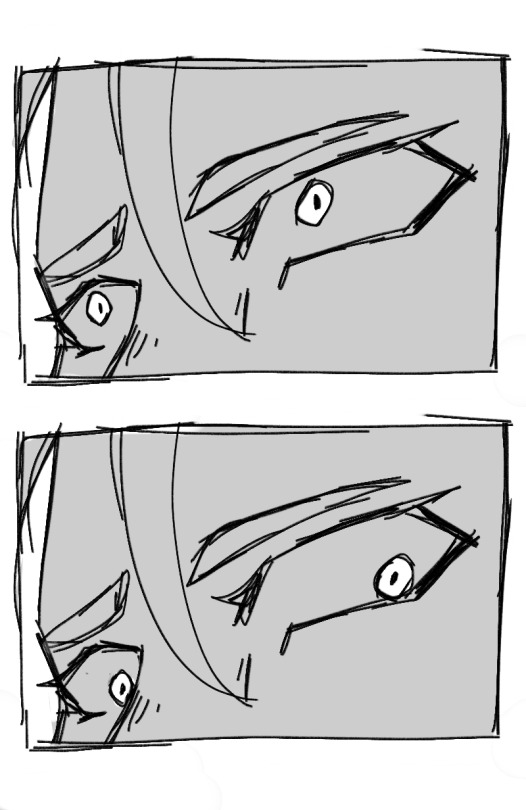

This intensity and disjointed personality is similar to the Fukuchi of the Bungou Stray Dogs universe. On one hand he’s wacky, hot-headed, and highly unpredictable, but on the other hand he’s calculating, cold, and cunning. Both are highly ambitious as well and would sit at positions of power for “national tranquility.”

Now you might be wondering why a pioneer such as Fukuchi doesn’t receive as much recognition now compared to his peers, like Fukuzawa Yukichi, the face of the 10000 yen bill. Huffman lists a few possible reasons for this such as 1.) His aforementioned “disagreeable” personality, 2.) His failure to concentrate his energy into any one particular cause or field (back and forth with writing for the newspaper, fiction (Mirror Lion, the BSD ability), and somewhere lingering about in politics). But I believe those listed by Brown ring truer to the reality of it all: mainly, that his interests remained political and diplomatic, incapable of stirring much change in Japanese society.

Honestly, I couldn’t really tell what exactly Fukuchi’s ideals were. Maybe I just don’t understand politics or history enough, but I just find reading about the rapid and contradictory changes in his actions is just confusing. For example, Fukuchi would become pro-Meiji government for a time, although the likely explanation is that he did find some policies he agreed with. A better example yet is he’d advocate for a constitutional government, then later draft a document securing absolute power to the Emperor. This contradiction may be solved, at least according to Huffman, by considering Fukuchi’s view on the Japanese monarchy: its sovereignty is “unlike European tyranny” since he believed in the benevolence of the Emperor. It would “violate Japanese history” to believe otherwise. Is it absolute faith in his country’s sovereignty that drove him here? Or stubbornness and naïveté? Whichever the answer was, the changing tides of the era would drive him out of his own mind… literally.

After 1882, newspapers that prioritized faithful and objective reporting of news, like Fukuzawa’s Jiji Shimpou (Current Events), would soon dominate as public interest in politics declined significantly. Fukuchi’s obstinacy in maintaining the old ways did harm for the Nichi Nichi, lowering sales and eventually forcing the company to fire him. This makes sense from a business perspective, but from a highly traditional Japanese viewpoint, it is “an act of tyranny.” He left the political scene a bitter man.

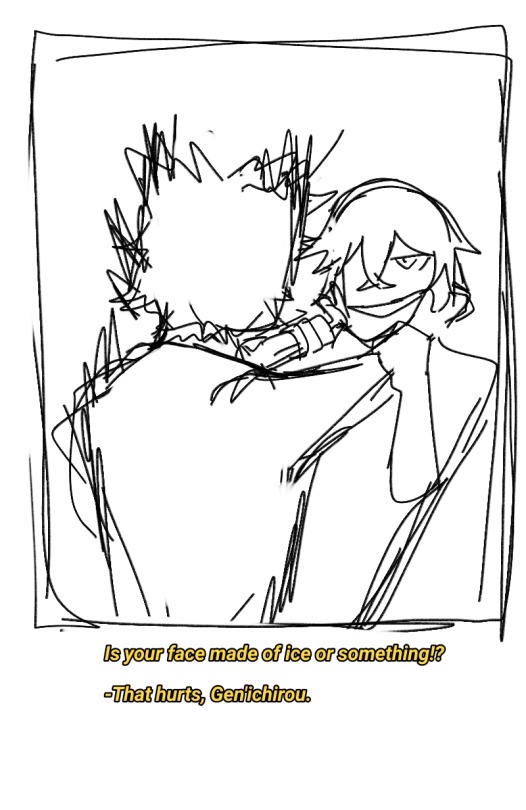

There is another immediate reason for Fukuzawa’s lasting impact. Despite having similar goals with Fukuchi, Fukuzawa had someone to pass on his ideas to: an English translator and biographer to record his life, his own sons (Sutejirou took over his father’s newspaper, Momosuke, although adopted, became a successful businessman and brought hydroelectric power to the nation), and of course, the university he founded: Keio University. BSD’s Fukuzawa has the ADA to carry on his visions and his life’s purpose, while Fukuchi’s sham of an organization already had two turn their backs on him. (Not sure where Teruko and Tetcho lie as of now, although I think Teruko would be the only one to stick with Fukuchi to the end to some extent, even though irl Fukuchi and Suehiro had a lot in common).

Ultimately, I think that BSD Fukuchi’s demise will be brought about by his arrogance and ambition. Not having any true convictions, goals, or family, he’ll have nothing to fall on once he slips from the tremendous summit he made for himself.

There might be redemption for him, though. I’ve shared in a different post the following quote:

"When Fukuzawa died, Fukuchi wrote rather plaintively: In 1874, when I was editing Tokyo Nichi Nichi, he said to me, 'You have taken up the newspaper business; that is wonderful. Be careful though not to get tied too much to the government. If you become too closely tied, they will mislead you.' In the end, they did... Ah, you were a good friend, a trustworthy friend. You did not let me down; I let you down."

Perhaps BSD Fukuchi would realize that his jealousy and hatred for his long-time and only true friend was based on nothing. But as to whether or not it will happen soon, we’ll only have to wait and see.