Author of “The Little Book of Revelation.” Get your copy now!!https://www.xlibris.com/en/bookstore/bookdetails/597424-the-little-book-of-revelation

447 posts

OPEN ACCESS AND THE BIBLE: The Bible And Interpretation

OPEN ACCESS AND THE BIBLE: The Bible and Interpretation

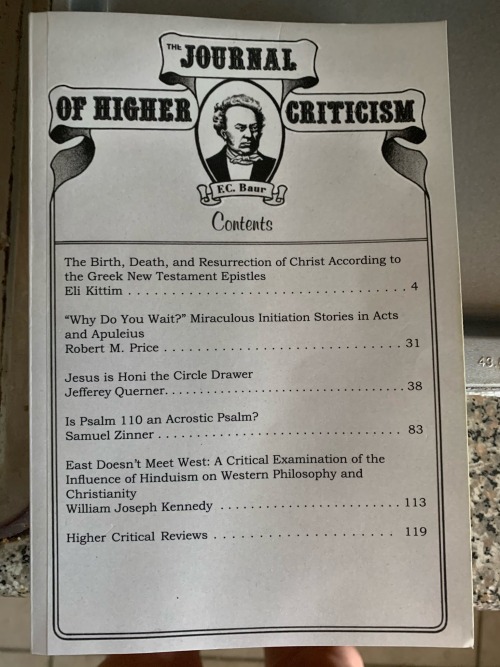

This is Eli Kittim’s academic monograph——published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 13, no. 3 (2018), page 4—-entitled, "The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Christ According to the Greek New Testament Epistles."

To view or purchase, click the following link:

https://www.amazon.com/Journal-Higher-Criticism-13-Number/dp/1726625176

_______________________________________________

-

koinequest liked this · 2 years ago

koinequest liked this · 2 years ago

More Posts from Eli-kittim

BIBLE EXEGESIS RESOURCES LIST (ONLINE)

Compiled by Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

Critical Bible Commentaries

https://libguides.twu.ca/religiousstudies/ecommentariesNT

Bryan College Library - Bible Study Resources - Compiled by Kevin Woodruff, M. Div, MS

https://library.bryan.edu/christian-studies-subject-guide/bible-study-resources

Interlinear Greek English Septuagint Old Testament (LXX)

https://archive.org/details/InterlinearGreekEnglishSeptuagintOldTestamentPrint/page/n5

Hebrew---English Interlinear Bible (Old Testament)

https://www.logosapostolic.org/bibles/interlinear_ot1.htm

Greek—English Interlinear Bible (New Testament)

https://www.logosapostolic.org/bibles/interlinear_nt.htm

Academic Bibles: The Hebrew OT, the Greek NT, the Septuagint, and the Latin Bible—which scholars prefer to use for research and publications—share the same link:

1) Hebrew Old Testament following the text of the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia

2) Greek New Testament following the text of the Novum Testamentum Graece (ed. Nestle-Aland), 28. Edition and the UBS Greek New Testament 5. Edition.

3) Greek Old Testament following the text of the Septuagint (ed. Rahlfs/Hanhart)

4) Latin Bible (Biblia Sacra Vulgata) following the text of the Vulgate (ed. Weber/Gryson)

5) King James Version

6) English Standard Version

7) NetBible

8)Luther-Bible 1984

https://www.academic-bible.com/en/online-bibles/novum-testamentum-graece-na-28/read-the-bible-text/

God’s Gender in Contextual Theology: Should We Preserve the Biblical Text in Light of New Age Interpretations?

By Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

I’m all for women’s rights, and I admit that in heaven there is no gender (Gen. 1:26-27; Mk. 12:25). I also know that many members of the LGBTQ+ community have been **reborn** in God. It’s also true that the masculine form of God is sometimes added to the English Bible translations, as Bruce Metzger argues.

However, from a textual perspective, I disagree with the idea that every name of God in the Bible means God/dess in its original language, as some feminist theologians contend. Although conventional Jewish theology doesn’t ascribe the notion of sex to God, it’s clear that the gender of God in the Tanakh is presented with masculine grammatical forms & imagery. For example, in the Hebrew Bible, Elohim is masculine in form. Also, when referring to YHWH, the verb vayomer (“he said”) is definitely masculine; we never find vatomer, the feminine form. In Psalms 89:26, God is explicitly referred to as “Father”:

He shall cry unto me, Thou art my Father,

My God, and the rock of my salvation.

In Isaiah 63:16, God is directly addressed as “our Father":

Thou, O Jehovah, art our Father; our

Redeemer from everlasting is thy name.

The same holds true in the Greek New Testament. For example, Κύριος (Kyrios) is a Nominative Masculine Singular noun which means “Lord.” Θεὸς (Theos) is a Nominative Masculine Singular noun which means God. In Luke 1:68, the definite article ὁ (ho), which refers to the God of Israel (ὁ θεὸς τοῦ Ἰσραήλ), is a Nominative Masculine Singular (he). None of these phrases referring to the Lord (ό Κύριος) or to God (ό Θεός) have feminine forms in the original Koine Greek. Even the incarnated God is said to be male (see Rev. 12:5)!

However, many modern Bible translations furnish us with new additions, paraphrases, and grammatical forms that clearly deviate from the Biblical texts. They do not remain faithful to the original biblical languages in preserving their literal meanings. For example, there are numerous modern Bible translations——such as the NLT, the CEV, and the NRSV——which attempt to reword the original texts by adopting gender-neutral language. This is not simply a benign translation philosophy based on a feminist biblical interpretation, but it can also be seen as a tool for political activism in trying to change gender perceptions and alter the Bible’s authorial intent. This is theologically dangerous because when we tamper with the Bible’s grammatical structures we gradually lose the precise words of the revelations as they were given in their original forms. According to Wayne Grudem, the translator’s job is to translate the original language accurately and precisely rather than to offer opinions regarding gender-related questions.

The doctrine of verbal plenary inspiration——the notion that each word was meaningfully chosen by God——supersedes the cultural milieu by virtue of its inspired revelation. Therefore, the language from which the text is operating must be preserved without additions, subtractions, or alterations (cf. Deut. 4:2; Rev. 22:18-19). Accordingly, it is incumbent on the Biblical scholars to maintain the integrity of the text.

For example, since the mid-nineteenth century, the New Testament was not only significantly changed by the Westcott and Hort text but it has also been evolving gradually with culturally sensitive translations regarding gender, sexual orientation, racism, inclusive language, and the like. Contextual theology has broadened the scope of the original text by adding a whole host of modern political and socioeconomic contexts (e.g. critical theory, feminist theology, etc.) that lead to many misinterpretations because they’re largely irrelevant to the core message of the New Testament and the teachings of Jesus!

The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of Christ According to the Greek New Testament Epistles

Published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 13, no. 3 (2018)

By Award-Winning Goodreads Author Eli Kittim 🎓

https://acrobat.adobe.com/link/review?uri=urn:aaid:scds:US:6b2a560b-9940-4690-ad29-caf086dbdcd6

Both Iris & Toxon mean Rainbow in the Bible

By Eli Kittim 🎓

All the Evidence Points to a Christ-Like Figure in Rev. 6.2

In this study I want to focus primarily on two words, iris & toxon, in order to show how they completely change our understanding of Revelation 6.2. But before I do this, I would first like to show you some proofs concerning the implied benevolence of the White horseman of the Apocalypse. That the white horse is a symbol of purity and righteousness is multiply attested by its linguistic usage patterns. For example, the phrase “and behold, a white horse,” in Rev. 19.11, is identical to the one used in Revelation 6.2. In other words, the two white horses of Revelation 19 & 6 represent the exact same figure who “is called Faithful and True” (Rev. 19.11)! That’s why Irenaeus, a second century theologian, held the same view, namely, that the first rider of the white horse who is depicted as a peacemaker represents Jesus Christ (Mounce, Robert H. The Book of Revelation. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Rev. ed. [Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1997], p. 141).

This is also confirmed by the type of crown the rider of the white horse wears. Stephanos “crowns” are typically worn by believers and victors in Christ (see e.g. the Greek text of Matthew 27.29; James 1.12; 2 Timothy 4.8; 1 Peter 5.4; Revelation 2.10; 4.4; 14.14)! All these proofs clearly show that the white horseman of Rev. 6.2 is neither deceptive nor evil, as many Bible commentators would have us believe!

The Hebrew Bible Uses the Word Bow for Rainbow

In the New Testament, the Greek noun ἶρις (iris) means “rainbow” (see https://biblehub.com/greek/2463.htm). Curiously enough, the Greek noun τόξον (toxon), which we find in Rev. 6.2, means “bow” but——as we shall see——it also means “rainbow” (see https://biblehub.com/greek/5115.htm). Τόξον can be seen as a contraction for ουράνιον τόξον (rainbow), from Ancient Greek οὐρανός ("heaven") + τόξον ("bow").

Given that the Greek noun “iris” is the most widely used term for “rainbow” in the New Testament, some commentators argue that since the word in Rev. 6.2 is “toxon,” not “iris,” it means that “toxon” (τόξον) cannot possibly refer to a rainbow. However, many notable Bible commentators, such as Chuck Missler, have said that the “bow” (toxon) in Rev. 6.2 appears to represent the “rainbow” of Genesis 9.13. In other words, the bow (toxon) represents the peace-covenant of Genesis 9.13. The actual verse in Genesis 9.13 (NRSV) reads:

“I have set my bow in the clouds, and it shall be a sign of the covenant between me and the earth.”

Bear in mind that Genesis 9.13 uses the Hebrew phrase qaš·tî (קַשְׁתִּ֕י), which means “my bow.” It comes from the Hebrew noun קֶשֶׁת (qesheth), which means——wait for it——a bow (https://biblehub.com/hebrew/7198.htm).

The Septuagint (LXX) Translates the Hebrew Word for Rainbow with the Greek Word Toxon

Further evidence that “toxon” (bow) can mean “rainbow” comes from the Septuagint, an early Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible. Lo and behold, the Septuagint translates “rainbow” as τόξον (toxon) in Genesis 9.13!

Thus, this brief study illustrates my point, namely, that “iris” and “toxon” are interchangeable in the Bible! The Septuagint (LXX) translation of Genesis 9.13 by L.C.L. Brenton reads as follows:

τὸ τόξον μου τίθημι ἐν τῇ νεφέλῃ, καὶ ἔσται εἰς σημεῖον διαθήκης ἀνὰ μέσον ἐμοῦ καὶ τῆς γῆς.

Translation:

“I set my bow in the cloud, and it shall be for a sign of covenant between me and the earth.”

Conclusion

Therefore, both “iris” and “toxon” mean “rainbow” in the Bible! They are interchangeable terms. This means that the rider of the “white horse … [who] had a bow” (τόξον), in Rev. 6.2, is symbolically holding the “rainbow,” which represents the covenant of peace between God & man in Genesis 9.13!

Should Women Preach in Church?

By Author Eli Kittim 🎓

During a time when *women* were considered second-class citizens, Christianity held some of them in the utmost esteem and regard. As a case in point, the very first person to ever see Jesus alive after his purported resurrection was a *woman* named Mary Magdalene! In the Old Testament, Miriam prophesied and addressed the nation, Deborah was the chief prophetess who commanded armies and was the 4th Judge of Israel, while Huldah was an advisor to the King, as well as a principal prophetess in the Nevi'im (Prophets) portion of the Hebrew Bible. Does that sound like women who were NOT permitted to *speak* out loud or to teach? Of course not!

In the New Testament, Paul permitted Phoebe, a female deacon, to recite scripture to a house church. Moreover, in Romans 16.7, Paul refers to a certain *woman* named Junia (Ἰουνίαν) as being “highly respected among the apostles.” Paul uses the Greek term ἐπίσημοι, which means “notable,” to refer to both Andronicus and Junia. The general scholarly presumption has been that Junia was Andronicus’ wife, although they may have been siblings, father and daughter, friends or acquaintances, and they could have been Paul’s kinsmen biologically, spiritually, or even metaphorically. The word that Paul employs to refer to Andronicus and Junia is ἐπίσημοι, which means “notable,” “illustrious,” “outstanding,” relating to office or position. So, a *woman* in first-century Palestine is given the highest honor by being referred to as a notable or outstanding apostle! This suggests that she can certainly hold her own in any discursive argument or Biblical debate.

There are certain precepts in the Old Testament that continue to be observed today, while there are others that are not. For example, the ceremonial law is no longer applicable. It once related to Israel's worship (see Lev 1.1-13). However, following the purported death and resurrection of Jesus these laws were no longer necessary.

Then there was the Civil Law. This law dictated and governed Israel's daily living (see e.g. Deut 24.10-11). However, our modern culture and society are so different that these outdated guidelines no longer apply. Even if we believe in the inspiration of scripture, we still have to consider some of these guidelines as cultural codes of conduct that were specific for that particular historical period. They had a historical significance but are no longer appropriate. For example, the prescriptions on beards (Lev. 19.27), or on hair (Lev. 21.5), the types of fabrics or clothes that were permissible, as well as the dietary laws were all part of the Sitz im Leben, namely, that particular historical period which has very little to do with our own. And that’s why they have been discarded.

Similarly, Paul’s suggestions about how *women* should dress or behave in church were part of the patriarchal social norms and have more to do with first-century Palestinian culture than with *women’s* ultimate purpose in pastoral care (see 1 Cor. 11.5; 1 Tim. 3.11). Some of these requirements are historically-specific and are therefore no longer applicable in today’s society in which independent *women* have become notable scholars, CEOs, and very successful in society at large.

Since the Holy Spirit came upon both men and women during the Pentecost (Acts 1.14-15), scripture therefore implies that *women* are equal in terms of spiritual discernment. And since Paul says in Galatians 3.28 that “There is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus,” then there can’t be any discussion about gender inequality concerning the sexes. According to Romans 2.11, “God does not show favoritism” (cf. Eph. 5.21). This means that there should not be any prejudice or discrimination against female scholars when it comes to pastoral care. Thus, *women* can certainly preach in the church! The basic qualifications for being a pastor are conversion and integrity. Just like Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said: people should “not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” In the same way, *women* should not be judged by their gender but by the content of their character! If *women* can earn a Doctor of Theology degree (ThD), then that means they are certainly qualified to teach. In the final analysis, there’s no Biblical precedent which explicitly forbids women from assuming a role of spiritual authority.