Biblicalcriticism - Tumblr Posts

Does God Create Evil?: Answering the Calvinists

By Award-Winning Author Eli Kittim

——-

Calvinism Has Confused God's Foreknowledge With His Sovereignty

Dr. R.C. Sproul once said:

There is no maverick molecule if God is

sovereign.

That is to say, if God cannot control the smallest things we know of in the universe, such as the subatomic particles known as “quarks,” then we cannot trust him to keep His promises. But just because God set the universe in motion doesn’t mean that every detail therein is held ipso facto to be caused by him. God could still be sovereign and yet simultaneously permit the existence of evil and free will. This is not a contradiction (see Compatibilism aka Soft determinism). It seems that Calvinism has confused God’s foreknowledge with his sovereignty.

Calvinists often use Bible verses out-of-context to support the idea that God is partial: that he plays favorites with human beings. They often quote Exodus 33.19b (ESV):

I will be gracious to whom I will be gracious,

and will show mercy on whom I will show

mercy.

But the only thing that this verse is saying is that God’s grace is beyond human understanding, not that God is partial and biased (cf. Rom. 11.33-34). By contrast, the parable of the vineyard workers (Mt 20.1–16) promotes equality between many different classes of people. One interpretation of this parable would be that late converts to Christianity earn equal rewards along with early converts, and there need be no jealousy among the latter. This can be understood on many different levels. For example, one could view the early laborers as Jews who may resent the Gentile newcomers for being treated as equals by God. Some seem to get more rewards, others less, depending on many factors unbeknownst to us. But the point of the parable is that God is fair. No one gets cheated. However, in Calvinism, God is not fair. He does as he pleases. He creates evil and chooses who will be saved and who will be lost. This view is more in line with the capricious gods of Greek mythology than with the immutable God of the Bible.

That’s why Calvinism speaks of limited atonement. Christ’s atoning death is not for everyone, but only for a select few. You cannot look an atheist in the eye and tell them that Christ died for you. You’d be lying because, according to Calvinism, he may not have died for them. So the story goes...

But that’s a gross misinterpretation. Romans 8.29-30 doesn’t say that at all. It’s NOT saying that God used his powers indiscriminately to influence Individuals in some cases, but not in others. Nor does it follow that God played favorites and decided at the outset that some will be saved, and others not (tough luck, as it were). Not at all. All it says is that God can *foresee* the future!

God doesn’t CAUSE everything to happen as it does, but he does SEE what will happen. So, insofar as God was able to “see” who would eventually submit to his will (and who would not), one could say that God “foreknew” him. In Romans 8.29, the Greek term προέγνω comes from the word προγινώσκω (proginóskó), which means “to know beforehand” or to “foreknow.” It doesn’t imply determinism, the notion that all events in history, including those of human action, are predetermined by extraneous causes, and that people have no say in the matter, and are therefore not responsible for their actions. It simply means to know beforehand. That’s all. Case in point, Isaiah, Daniel, and John the Revelator saw the future; but they didn’t cause it.

God would never have predestined some people to be eternally lost and some to be eternally saved. That would not be just. Similarly, Romans 8.29-30 is only referring to those individuals whom God “foreknew” (προέγνω) that would meet the conditions of his covenant, those are the same he predestined (προώρισεν), called (ἐκάλεσεν), justified (ἐδικαίωσεν), and glorified (ἐδόξασεν)! Otherwise, how could God have possibly predestined those who he foresaw that would NOT meet the conditions of his covenant?

The Greek term προώρισεν (proōrisen; predestined) is derived from the word προορίζω (proorizó), which means “to predetermine” or “foreordain.” In other words, those whom God could *foresee* in the future as being faithful, those same individuals he pre-approved to be conformed to the image of his son. So, by “predestination” God simply means that he’s “declaring the end from the beginning” (Isa. 46.9-10 NASB). It’s not as if God was the direct cause of their decision or free choice. He simply foresaw those who had already chosen to be conformed to the image of his son of their own accord. Notice that in Rom. 8.29 (Berean Literal Bible), the text says that BECAUSE God foreknew them, he predestined them. This means that the *foresight* came first. Since God could see the outcome, he “foreknew” who would be lost and who would be saved:

because those whom He foreknew, He also

predestined to be conformed to the image

of His Son.

——-

Does John Piper represent Biblical Christianity?

Theologian and pastor John Piper cites Acts 4.27-28 (ESV) to prove his point that God determines everything that happens:

for truly in this city there were gathered

together against your holy servant Jesus,

whom you anointed, both Herod and

Pontius Pilate, along with the Gentiles and

the peoples of Israel, to do whatever your

hand and your plan had predestined to take

place.

Piper says, when you understand the complete sovereignty of God, that is to say, how he is behind everything, that he is implicated in every aspect of existence, you’ll go crazy. Why? This occurs, I suspect, because the person you thought was your best friend turns out to be your worst enemy. How can you trust him? Piper says,

He [God] governed the most wicked thing

that ever happened in the world, the

crucifixion of my savior.

Piper says that there is no randomness in the universe, and that God is behind the Tsunamis and everything else that occurs on our planet. That would imply that God is behind the earthquakes, the hurricanes, the train wrecks, the airplane crashes, the massacres, the terrorist attacks, the racist attacks, the rapes, the violent riots, the Holocaust, the Third Reich, the Manson murders, the serial killings, cannibalism, the world wars, the abortions, the beheadings, the heinous crimes, the shootings, beatings, & stabbings of the elderly, and the filicides and genocides of history. God’s behind it all. And if you contemplate this idea, it will drive you mad, says John Piper. So, in order to stay sane, he suggests that we focus on the Cross. We have to believe that God nevertheless loves us and that he was behind the murder of Jesus for our salvation. This will keep us safe from harm; from going mad, that is. Really?

In other words, God’s dictatorist regime or tyrannical authority works much like the Mafia, a secret organization or crime syndicate which controls everything from the street corner thugs to the highest levels of government. God is like a mafia boss who puts out a contract to “whack” somebody but, instead of killing him himself and taking the blame, he orders an underboss (Satan) to do his dirty work. In other words, he hires accomplices to kill people on his behalf because he’s such a coward that he doesn’t want to take the responsibility and do it himself, or to be seen as evil, yet he’s the real cause of everything, good and evil. A literal or fundamentalist interpretation of the Old Testament will no doubt lead to that conclusion (cf. Isa. 45.7). This is also the god of the Gnostics, the inferior creator-god (or demiurge) that was revealed through Hebrew scripture, who was responsible for all instances of falsehood and evil in the world!

But is this a sincere, honorable, and reliable person whom you could trust? Or is this a vile, dishonest, and despicable person who pretends to be something he is not? Does this god deserve our worship? Is he not a liar? Is this a truly loving, Holy God, or is he rather a cruel, deceitful, and merciless beast that hides behind a veneer of righteousness, much like the mafia bosses and the corrupt heads of state?

Then, after depicting a gruesome picture of a cold blooded killer-God who would order a hit on women and innocent children (cf. 1 Sam. 15.3), Piper cites Isa. 53.10:

Yet it was the will of the Lord to crush him

[christ] with pain.

He concludes:

Therefore the worst sin that was ever

committed was ordained by God.

Piper exclaims, “The answer is yes, he controls everything, and he does it for his glory and our good.” This is the God of Calvinism, fashioned from the pit of hell itself, which depicts God’s rule as a deep state or a totalitarian government, “A celestial North Korea,” in the words of the critic Christopher Hitchens.

What ever happened to the attribute of omnibenevolence, the doctrine that God is all-good, sans evil (cf. Ps 106.1; 135.3; Nah. 1.7; Mk 10.18)? Isaiah 65.16 calls him “the God of truth” (cf. Jn 17.17), while Titus 1.1-2 asserts that God “never lies.” Psalm 92.15 (NIV) declares:

The LORD is upright; he is my Rock, and

there is no wickedness in him.

So, there seems to be a theological confusion in Calvinism about what God does and doesn’t do. Predestination is based on foreknowledge, not on the impulsive whims of a capricious deity. To “cause” is one thing; to “foreknow” is quite another.

At a deeper, philosophical level we’re talking about the problem of evil: who’s responsible for all the suffering and evil in the world? Piper would say, God is. Blame it on God. I would say that this teaching not only contradicts the Bible but also the attributes of God. If hell was prepared for the devil and his angels (Mt 25.41), and if God is held accountable for orchestrating everything, then the devil cannot be held morally responsible for all his crimes against humanity. Besides, doesn’t scripture say that Christ “went about doing good and healing all who were oppressed by the devil”? (Acts 10.38 ESV). Yet, according to Calvinism, God not only creates evil but is himself ipso facto evil! Thus, neither John Piper nor Calvinism represent Biblical Christianity! Rather, this is an aberration, a contradiction, a false doctrine. 1 Timothy 4.1 (CEV) warns:

God's Spirit clearly says that in the last

days many people will turn from their faith.

They will be fooled by evil spirits and by

teachings that come from demons.

In the following video, a question was posed to Calvinist pastor John Piper:

Has God predetermined every detail in the

universe, including sin?

To which Piper replied:

YES!

Therefore, in Calvinism,

God has become Satan!

Calvin’s Refutations from His Own Published Work: A Critical Review by Author Eli Kittim

Excerpted from John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian religion, Book 3, ch 23.

——-

Calvin’s god Chooses Whatever He Pleases and We Have No Right to Question his Choices

In Institutes, Book 3, ch 23, Calvin says that god chooses whatever he pleases, and we have no right to question his choices. But isn’t that tantamount to saying that “he does as he pleases” as opposed to acting according to the principles of truth and wisdom? Calvin writes:

Therefore, when it is asked why the Lord did

so, we must answer, Because he pleased.

But if you proceed farther to ask why he

pleased, you ask for something greater and

more sublime than the will of God, and

nothing such can be found. … This, I say,

will be sufficient to restrain any one who

would reverently contemplate the secret

things of God.

Yet isn’t that precisely what Calvin is doing? Inquiring into the “the secret things of God”? Calvin’s argument can be summarized as follows: men are, by nature, wicked, so if god has predestined some to eternal hellfire, why do they complain? They deserve it. He exclaims:

Accordingly, when we are accosted in such

terms as these, Why did God from the first

predestine some to death, when, as they

were not yet in existence, they could not

have merited sentence of death? let us by

way of reply ask in our turn, What do you

imagine that God owes to man, if he is

pleased to estimate him by his own nature?

As we are all vitiated by sin, we cannot but

be hateful to God, and that not from

tyrannical cruelty, but the strictest justice.

But if all whom the Lord predestines to

death are naturally liable to sentence of

death, of what injustice, pray, do they

complain?

He continues his thought that even though god condemned them to hellfire long before they were even born, or had done anything to warrant such an outcome, they nevertheless deserve it and should not complain. Calvin says:

Should all the sons of Adam come to

dispute and contend with their Creator,

because by his eternal providence they

were before their birth doomed to perpetual

destruction, when God comes to reckon

with them, what will they be able to mutter

against this defense? If all are taken from a

corrupt mass, it is not strange that all are

subject to condemnation. Let them not,

therefore, charge God with injustice, if by

his eternal judgment they are doomed to a

death to which they themselves feel that

whether they will or not they are drawn

spontaneously by their own nature.

But if this decree was foreordained by an absolutely sovereign god even before people were born and prior to having committed any transgressions, why are they held accountable for their sins? It appears to be a contradiction. Curiously enough, John Calvin,

admit[s] that by the will of God all the sons

of Adam fell into that state of wretchedness

in which they are now involved; and this is

just what I said at the first, that we must

always return to the mere pleasure of the

divine will, the cause of which is hidden in

himself.

So he admits that we all sinned “by the will of God” and that god does as he pleases, yet he concludes: who are we to question god’s decisions? But is this a proper explanation of predestination that fully justifies god’s justice, or is it rather an incoherent and unsatisfactory answer? Calvin asserts:

They again object, Were not men

predestinated by the ordination of God to

that corruption which is now held forth as

the cause of condemnation? If so, when

they perish in their corruptions they do

nothing else than suffer punishment for that

calamity, into which, by the predestination

of God, Adam fell, and dragged all his

posterity headlong with him. Is not he,

therefore, unjust in thus cruelly mocking his

creatures? … For what more

seems to be said here than just that the

power of God is such as cannot be

hindered, so that he can do whatsoever he

pleases?

Calvin says “How could he who is the Judge of the world commit any unrighteousness?” But Calvin doesn’t explain how that is so except by way of assumptions, which are based on the idea that god acts as he pleases and does as he wills. But that’s circular reasoning. It’s tantamount to saying that something is true because I assume that it is, without any proof or justification that it is true. It’s a fallacious argument. Calvin argues thusly:

It is a monstrous infatuation in men to seek

to subject that which has no bounds to the

little measure of their reason. Paul gives the

name of elect to the angels who maintained

their integrity. If their steadfastness was

owing to the good pleasure of God, the

revolt of the others proves that they were

abandoned. Of this no other cause can be

adduced than reprobation, which is hidden

in the secret counsel of God.

Reprobation, according to Calvin, is based on the notion “that not all people have been chosen but that some have not been chosen or have been passed by in God's eternal election.” But if no one deserves the merits of salvation, and if no one obeys the will of god except by god’s grace, then how is god’s election justified? Calvin’s response that it’s justified because god is just is not an explanation: it is a tautological redundancy. Calvin’s reply would be: god decided not to save everybody, and who are we to criticize him? Unfortunately, that’s not an adequate or satisfactory answer.

God’s decision to save some people is called election, and his decision not to save other people is called preterition. According to Calvinism, god chooses to bypass sinners by not granting them belief, which is equivalent, in a certain sense, to creating unbelief (by omission) in them. In other words, god chooses to save some, but not others. And it pleases him to do so.

Is this truly the love of Christ that is freely offered to all? By contrast, according to Scripture, God wishes to save everyone without exception (1 Timothy 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9; Ezekiel 18:23; Matthew 23:37). When Matthew 22.14 says, “For many are called, but few are chosen,” it clearly shows that those that are not chosen are still “called.” It doesn’t mean that god did not choose them for salvation. It means they themselves chose to decline the offer of their own accord. How can one logically argue that god wants all people to be saved but only chooses to save some of them? It is a contradiction in terms. And then to attribute this injustice and inequality to what appears to be an “arrogant” god who does as he pleases is dodging the issue.

Biblical Predestination Doesn’t Imply god’s Sovereignty But God’s Foreknowledge

Calvinists employ Ephesians 1.4-5 to prove that god clearly elected to save some (and not to save others) before the foundation of the world. But that is a misinterpretation. The entire Bible rests on God’s foreknowledge, his ability to see into the future: “declaring the end from the beginning and from ancient times things not yet done” (Isa. 46.10; cf. Jn 16.13; Rom. 1.2; Acts 2.22-23; 10.40-41). In other words, God did not choose to save some and not to save others. Rather, through his *foreknowledge* he already knew (or foreknew) who would accept and who would decline his offer. That’s why Rom. 8.29 (BLB) says, “because those whom He foreknew, He also predestined.” This explanation is consistent with God’s sovereignty and man’s free will, as well as with the justice and righteousness of God! It is reprehensible to suggest that god would choose by himself who would be eternally saved and who would be eternally condemned. That would not be a fair, just, and loving god. However, Calvin rejects prescience on account “that all events take place by his [god’s] sovereign appointment”:

If God merely foresaw human events, and

did not also arrange and dispose of them at

his pleasure, there might be room for

agitating the question, how far his

foreknowledge amounts to necessity; but

since he foresees the things which are to

happen, simply because he has decreed

that they are so to happen, it is vain to

debate about prescience, while it is clear

that all events take place by his sovereign

appointment.

So, Calvin ultimately places all responsibility and accountability on god, who has foreordained all events “by his sovereign appointment.” But if hell was prepared for the devil and his angels (Mt 25.41), and if god is held accountable for orchestrating everything, then the devil cannot be held morally responsible for all his crimes against humanity. Therefore, according to Calvinism, it would logically follow that god is ultimately responsible for evil, which would implicate himself to be ipso facto evil! There’s no way to extricate god from that logical conclusion.

god Created Evil at his Own Pleasure

In Calvin’s view, god decreed that Adam should sin. In other words, god decrees all sin, which is a sign of his omnipotence and will. How revolting! He writes:

They deny that it is ever said in distinct

terms, God decreed that Adam should

perish by his revolt. As if the same God, who

is declared in Scripture to do whatsoever he

pleases, could have made the noblest of his

creatures without any special purpose.

They say that, in accordance with free-will,

he was to be the architect of his own

fortune, that God had decreed nothing but

to treat him according to his desert. If this

frigid fiction is received, where will be the

omnipotence of God, by which, according to

his secret counsel on which every thing

depends, he rules over all?

Invariably, Calvin places the blame indirectly on god. Calvin holds to an uncompromising hard determinism position, without the slightest possibility of free will, by claiming that even god’s foreknowledge is “ordained by his decree”:

it is impossible to deny that God foreknew

what the end of man was to be before he

made him, and foreknew, because he had

so ordained by his decree.

If this isn’t an evil doctrine I don’t know what is. Calvin unabashedly declares that god created evil in the world “at his own pleasure.” He writes:

God not only foresaw the fall of the first

man, and in him the ruin of his posterity; but

also at his own pleasure arranged it.

Wasn’t Satan the one who supposedly arranged it? Hmm, now I’m not so sure … If god is the author of evil, why would he involve Satan in this script? In fact, Calvin insists that the wicked perish not because of god’s permission but because of his will. He says that “their perdition depends on the predestination of God … The first man fell because the Lord deemed it meet that he should: why he deemed it meet, we know not.” What a dreadful thing to say. It’s as if Calvin was under the inspiration of Satan, teaching “doctrines of demons” (1 Tim. 4.1 NKJV). Calvin writes:

Here they recur to the distinction between

will and permission, the object being to

prove that the wicked perish only by the

permission, but not by the will of God. But

why do we say that he permits, but just

because he wills? Nor, indeed, is there any

probability in the thing itself--viz. that man

brought death upon himself merely by the

permission, and not by the ordination of

God; as if God had not determined what he

wished the condition of the chief of his

creatures to be. I will not hesitate, therefore,

simply to confess with Augustine that the

will of God is necessity, and that every thing

is necessary which he has willed.

Calvin attempts to show that there’s no contradiction in his statement but, instead of providing logical proof, he once again resorts to circular reasoning, namely, that the accountability rests with an authoritarian god who does as he pleases:

There is nothing inconsistent with this when

we say, that God, according to the good

pleasure of his will, without any regard to

merit, elects those whom he chooses for

sons, while he rejects and reprobates

others.

Instead of admitting that this is his own wicked view of god, which certainly deserves rebuke and criticism, he suggests that this is the way god really is. In other words, he indirectly blames god by way of compliments. By insisting on god’s Sovereignty and omnipotence, he sets god up to take the blame for everything. Yet in his evasive and largely indefensible argument, he ends up justifying the seemingly “capricious” acts of god by saying that god is still just:

Wherefore, it is false and most wicked to

charge God with dispensing justice

unequally, because in this predestination he

does not observe the same course towards

all. … he is free from every accusation; just

as it belongs to the creditor to forgive the

debt to one, and exact it of another.

Conclusion

Just because God set the universe in motion doesn’t mean that every detail therein is held ipso facto to be caused by him. God could still be sovereign and yet simultaneously permit the existence of evil and free will. This is not a philosophical contradiction (see Compatibilism aka Soft determinism).

The Calvinist god is not fair. He does as he pleases. He creates evil and chooses who will be saved and who will be lost. He is neither trustworthy nor does he equally offer unconditional love to all! In fact, this view is more in line with the capricious gods of Greek mythology than with the immutable God of the Bible.

Calvin’s deity is surprisingly similar to the god of the Gnostics, who was responsible for all instances of falsehood and evil in the world! This is the dark side of a pagan god who doesn’t seem to act according to the principles of truth and wisdom but according to personal whims. With this god, you could end up in hell in a heartbeat, through no fault of your own. Therefore, Calvin’s god is more like Satan!

This is certainly NOT the loving, trustworthy, and righteous God of the Bible in whom “There is no evil” whatsoever (Ps 92.15 NLT; Jas. 1.13). Calvin’s god is not “the God of truth” (Isa. 65.16; cf. Jn 17.17), who “never lies” (Tit. 1.1-2), and who is all-good, sans evil (cf. Ps 106.1; 135.3; Nah. 1.7; Mk 10.18). Calvin’s theology does not square well with the NT notion “that God is light and in him there is no darkness at all” (1 Jn 1.5 NRSV)!

Thus, Calvin’s argument is not only fallacious, unsound, and unbiblical, but also completely disingenuous. For if “life and death are fixed by an eternal and immutable decree of God,” including the prearrangement of sin “at his own pleasure,” as Calvin asserts, then “to charge God with dispensing justice unequally” is certainly a valid criticism! Calvin harshly accused his critics of promulgating blasphemies, but little did he realize the greater blasphemies and abominations that he himself was uttering! A case in point is that he makes God the author of sin!

——-

What is Predestination?

By Bible Researcher, Eli Kittim

——-

Introduction

Predestination is the doctrine that all events in the universe have been willed by God (i.e. fatalism). It is a form of theological determinism, which presupposes that all history is pre-ordained or predestined to occur. It is based on the absolute sovereignty of God (aka omnipotence). However, there seems to be a paradox in which God’s will appears to be incompatible with human free-will.

The concept of predestination is found only several times in the Bible. It is, however, a very popular doctrine as it is commonly held by many different churches and denominations. But it’s also the seven-headed dragon of soteriology because of its forbidding controversy, which arises when we ask the question, “on what basis does God make his choice?” Not to mention, how do you tell people God loves them and that Jesus died for you?

If we study both the Old and New Testaments, especially in the original Biblical languages, we will come to realize that predestination doesn’t seem to be based on God’s sovereignty but rather on his “foreknowledge.” This is the *Prescience* view of Predestination, namely, that the decision of salvation and/or condemnation is ultimately based on an individual’s free choice!

——-

Free Will

John MacArthur argues that the salvation “offer is always unlimited, otherwise why would we be told to go into all the world and preach the gospel to every creature?” He went on to say, “The offer is always unlimited or man couldn’t be condemned for rejecting it.”

Let’s take a look at the Old Testament. Isaiah 65.12 (ESV) employs the Hebrew term וּמָנִ֨יתִי (ū·mā·nî·ṯî) to mean “I will destine,” which is derived from the word מָנָה (manah) and means to “appoint” or “reckon.” But on what basis does God make his choice of predestination to damnation (aka the doctrine of reprobation)? God says:

I will destine [or predestine] you to the

sword, and all of you shall bow down to the

slaughter, because, when I called, you did

not answer; when I spoke, you did not listen,

but you did what was evil in my eyes and

chose what I did not delight in.

It’s important to note that those who are condemned to damnation are predestined to go there because when God called them, they didn’t respond to his call. When God tried to enlighten them, they “did not listen,“ but instead “did what was evil” in his sight. In fact, they did what God disapproved of! That’s a far cry from claiming, as the Calvinists do, that God willed it all along. Notice that God’s predestination for the reprobates is not based on his will for them not to be saved, but rather because they themselves had sinned. This is an explicit textual reference which indicates that it was something God “did not delight in.” So, it’s not as if God predestined reprobates to hell based on his sovereign will, as Calvinism would have us believe, but rather because they themselves chose to “forsake the LORD” (Isa. 65.11).

The New Testament offers a similar explanation of God’s official verdict pertaining to the doctrine of reprobation, namely, that condemnation depends on human will, not on God’s will. John 3.16 (NIV) reads:

For God so loved the world that he gave his

one and only Son, that whoever believes in

him shall not perish but have eternal life.

Notice, it doesn’t say that only a limited few can believe and be saved by Jesus. Rather, it says “whoever believes in him [ἵνα πᾶς ὁ πιστεύων εἰς αὐτὸν] shall not perish but have eternal life.” That is, anyone who believes in Jesus will not be condemned but will be saved, and will therefore be reckoned as one of the elect. Verse 17 says:

For God did not send his Son into the world

to condemn the world, but to save the world

through him.

Once again, there’s a clear distinction between the individual and the world as a whole, as well as a contrast between condemning and saving the world, and we are told that the Son was sent to save the entire world. The next verse (v. 18) explains that condemnation itself ultimately lies not with God but with our own personal choices and decisions. “Whoever does not believe stands condemned already” (i.e. is predestined to condemnation):

Whoever believes in him is not condemned,

but whoever does not believe stands

condemned already because they have not

believed in the name of God’s one and only

Son.

Verse 19 puts this dilemma in its proper perspective and gives us the judicial verdict, as it were, that we are ultimately responsible for our actions:

This is the verdict: Light has come into the

world, but people loved darkness instead of

light because their deeds were evil.

This conclusion can be easily illustrated. In Rev. 3.20 (KJV), does Christ imply that man’s free will doesn’t really matter at all? Does he say?:

Behold, I stand at the door. Don’t worry, I

won’t bother knocking on the door. Your

your response is unnecessary. You don’t

even have to open the door. I will break it

down and force my way inside.

Is that what he says? No. He says:

Behold, I stand at the door, and knock: if

any man hear my voice, and open the door,

I will come in to him, and will sup with him,

and he with me.

God respects our free will. Notice the condition that is set before us: someone has to open the door, which is equivalent to granting Christ permission to come in and become a part of them. But the choice ultimately rests with us, not with God. Unless we say yes, nothing happens. We must answer the call (cf. Isa. 65.12) and respond in the affirmative, just as Mary did in the gospel of Luke (1.38 NASB):

‘may it be done to me according to your

word.’

Similarly, Mt. 22.14 clearly shows that those that are not chosen are nevertheless “called”:

‘For many are called, but few are chosen.’

What is more, according to the Biblical text, anyone can become a member of God’s family. Just because God already “foreknows” who will accept and who will reject his invitation doesn’t mean that people are held unaccountable. For Christ doesn’t only take away the sin of the elect, but of the entire world (Jn 1.29 NKJV):

Behold! The Lamb of God who takes away

the sin of the world!

First John 2.2 reads:

And He Himself is the propitiation for our

sins, and not for ours only but also for the

whole world.

In a similar fashion, Rev 22.17 (KJ) says:

Come. And let him that is athirst come. And

whosoever will, let him take the water of life

freely [δωρεάν].

That doesn’t sound to me like a “predestined” election in which only a select few will receive the water of life, but rather a proclamation that salvation is “freely” (δωρεάν) offered to anyone who desires it. Moreover, in 2 Pet. 3.9 (ESV), we are told that “The Lord” doesn’t want to condemn anyone at all:

[he’s] not wishing that any should perish,

but that all should reach repentance.

Is this biblical reference compatible with Calvin’s views? Definitely not! Calvin suggests that God is the author of sin and the only one who ultimately decides on who will repent and who will perish.

Unlimited Atonement

There seems to be a comparison and contrast between the “vessels of wrath prepared for destruction” (in Rom. 9.22), and the “vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory” (v. 23). But we cannot jump to any conclusions because the text doesn’t explicitly say that both classes of people are predestined either to election or condemnation by the sovereign will of God. Furthermore, the terms that are used, here, are not the same as the ones used for predestination elsewhere in the Bible. For example, the Greek term often used for “predestination” is προορίζω or proorizó (cf. Acts 4.28; Rom. 1.4; 8.29; Eph. 1.5, 11). However, the Greek word used in Rom. 9.22 is καταρτίζω (katartizó), which means to complete or prepare (not predestine). It could simply refer to the remainder of the population that will miss out on salvation. it doesn’t necessarily follow that these are predestined (κατηρτισμένα) to destruction.

The next verse employs the term προητοίμασεν (prepared) to refer to the elect, or the “vessels of mercy, which he has prepared beforehand for glory.” But caution is advised. The term used is proētoimasen (prepared), not proorizó (predestined). This expression can refer to that portion of the population that God adopted into his family and nourished into maturity. The text is unclear as to whether the term “prepared” suggests that God coerced them into “election” by overriding their free will, while they were kicking and screaming. Besides, their personal choice may have been *foreknown* and acknowledged from the foundation of the world. It still doesn’t prove predestination, as defined by Augustine and Calvin.

If, in fact, God predestined some to salvation and some to perdition, so that Jesus didn’t die for all people but only for a limited few, then it wouldn’t make any sense for the New Testament to say that Christ “gave himself a ransom for all.” Nor would God contradict himself by saying that “he desires everyone to be saved.” First Timothy 2.3-6 (NRSV) reads:

This is right and is acceptable in the sight of

God our Savior, who desires everyone to be

saved and to come to the knowledge of the

truth. For there is one God; there is also one

mediator between God and humankind,

Christ Jesus, himself human, who gave

himself a ransom for all [not for some].

Notice that Christ’s atonement potentially covers even sinners who are not yet part of the “elect.” In the following verse, observe what the text says. There were apostates who denied “the Lord who bought them.” This means that Christ’s atonement is not “limited”; it covers them, as well. Second Peter 2.1 (NKJV) reads:

But there were also false prophets among

the people, even as there will be false

teachers among you, who will secretly bring

in destructive heresies, even denying the

Lord who bought them, and bring on

themselves swift destruction.

Prescience (Foreknowledge)

The Greek term that is typically used for predestination is also used in Rom. 1.4 (ESV), namely, the term ὁρισθέντος (from ὁρίζω), which carries the meaning of “determining beforehand,” “appointing,” or “designating.” However, notice that, here, this term is translated as “declared”:

and was declared to be the Son of God in

power according to the Spirit of holiness by

his resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ

our Lord.

But was Jesus Christ predestined to be the Son of God? No. He already was the Son of God. Nevertheless, what he would perform in the future was “declared” beforehand, or announced in advance. This verse, then, demonstrates that the word “foreknown” would be a more accurate term than “predestined”!

Similarly, Rom. 8.29 (ESV) tells us that those he “foreknew” (προέγνω), the same God προώρισεν (from προορίζω), that is, foreordained, predetermined, or pre-appointed beforehand. And Rom. 8.30 goes on to say that those he προώρισεν (predetermined) were the same that God also called, justified, and glorified. Verse 29 says:

For those whom he foreknew he also

predestined to be conformed to the image

of his Son.

Notice that God’s *foreknowledge* temporally precedes predestination. If God actually chose to save some and not to save others before the foundation of the world, then his foreknowledge would be irrelevant. But since it is on this basis that God predestines, it doesn’t sound as if predestination is chosen on the basis of God’s sovereign will.

Conclusion

Acts 4.28 does say that God’s will προώρισεν (predetermined beforehand) what will happen. But it doesn’t necessarily follow that everything that has occurred in human history is based on the will of God (i.e. fatalism). And we don’t know to what extent God influences reality. So, we cannot jump to any conclusions that God is behind everything that happens. Why? Because with absolute responsibility comes absolute blame. Is God responsible for murder, or rape, or genocide? I think not! So, we are on safer ground if we acknowledge that God “foreknew” what would happen and declared it beforehand (cf. Isa. 46.10). This notion would be far more consistent with the Bible than placing the full blame for everything that has ever occurred in the world on God. This seems to be the Achilles' heel of Calvinism.

Ephesians 1.5 is another controversial verse. The Greek term used is προορίσας (from προορίζω), meaning “foreordain,” “predetermine,” or “pre-approve beforehand.” The verse reads:

he predestined us for adoption to himself as

sons through Jesus Christ, according to the

purpose of his will.

But what exactly does the term “will” mean, here? Does it refer to God’s choice to save only a limited few and no one else, or to his overall plan of salvation that includes all people? It seems as if God saved those who answered his invitation, as it were, which would explain why he has “foreknown” them and predestined them for glory. I think that the latter explanation seems far more compatible with the Bible by a preponderance of the evidence.

Finally, let’s look at Ephesians 1.11. The Greek term that is used is προορισθέντες (from proorizó), meaning to “predetermine” or “foreordain beforehand.” The verse says that we have been predestined according to his purpose. Granted, it does say that all things work according to God’s will. However, to be fair, we don’t know exactly how that works, and so we can’t offer premature assumptions and presuppositions, especially when they contradict other passages in the Bible.

It would be utterly foolish to suppose that the God of the universe does not affect, influence, or sustain his creation. The fact that he created the universe obviously implies that he had a purpose for it. So, I’m not discounting the notion that all things are, in a certain sense, guided by his ultimate purpose. However, I take issue with those thinkers who take it to the extreme and portray the deity as an authoritarian and capricious God who bypasses the principles of truth and wisdom and intervenes by forcibly coercing man's free will. That type of God is inconsistent with the infinitely wise, holy, true, and good God of the Bible. That is precisely why “Arminius taught that Calvinist predestination and unconditional election made God the author of evil” (Wiki)!

——-

How Old Was Abraham When He Left Haran?

By Bible Researcher Eli Kittim 🎓

The Apparent Contradiction

There’s a seeming contradiction in the Bible concerning Abraham’s age when he left Haran. The apparent contradiction is as follows. If Terah died when he was 205 years old, but fathered Abram when he was 70, then Abram must have been 135 years old when his father Terah died (as Gen. 11.26, 32 suggest), not 75, as Gen. 12.4 indicates. For the story to work without any discrepancies, Terah would literally have to be 130 years old when he fathered Abram. But it seemed as if he were only 70 years old. Hence the apparent contradiction. Below are the relevant citations that appear to contradict each other.

—-

Genesis 12.4 (ESV):

So Abram went, as the LORD had told him,

and Lot went with him. Abram was seventy-

five years old when he departed from

Haran.

Acts 7.2:

And Stephen said: ‘Brothers and fathers,

hear me. The God of glory appeared to our

father Abraham when he was in

Mesopotamia, before he lived in Haran.’

Acts 7.4:

Then he went out from the land of the

Chaldeans and lived in Haran. And after his

father died, God removed him from there

into this land in which you are now living.

Genesis 11.26:

When Terah had lived 70 years, he fathered

Abram, Nahor, and Haran.

Genesis 11.32:

The days of Terah were 205 years, and

Terah died in Haran.

—————

Apologetic Exegesis

The key passage is Gen. 11.26. The Hebrew text doesn’t explicitly say that *when* Terah was 70 years old he begat Abram. Rather, it puts it thusly (Gen. 11.26 KJV):

And Terah lived seventy years, and begat

Abram, Nahor, and Haran.

Nowhere is it explicitly mentioned that Terah had all 3 children when he was 70 years old. Nor is there any direct evidence that these children were triplets, or that they were born on the exact same date, month, or year. The verse in Gen. 11.26 merely indicates that after Terah reached a certain age——namely, 70 years old——he began to father children. But exactly when these children were actually born is unknown. The only thing that’s clear from Gen. 11.26 is that they were born after Terah had reached a certain age.

It’s quite possible, for example, that some of his children could have been born when Terah was 130 years old. Nothing in the text would contradict the timing of such a birth. As long as Terah fathered at least one child after he was 70, the rest could have been born anytime between Terah’s 70th and 205th birthday.

The order in which the names of Terah’s sons are listed may not reflect the precise chronological order in which the children were actually born. The text is simply indicating their order of importance. Given that Abram is a key figure in the Old Testament and the common patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, he’s obviously mentioned first:

there is yet a question whether Abram was

born first as listed, or perhaps he is listed

first because he was the wisest similar to

Shem, Ham, and Jafeth where Shem was

not the oldest, but was the wisest. … the

Talmud leaves the above question open.

(Wikipedia)

—————

Conclusion

Actually, Abram could have been 75 years old when he left Haran, as the text indicates (Gen. 12.4). And maybe he did leave Haran “after his father died” (Acts 7.4) at the age of 205 (Gen. 11.32). There is no contradiction with regard to the dates. The assumed contradiction is actually based on fallacious reasoning and speculation. It’s based on an eisegesis, that is, a misinterpretation of the text. Readers often assume that the text is telling us that Abram was born *when* Terah was 70 years old. But that’s a conjecture. The text doesn’t say that at all. All the text says is that once Terah reached a certain age, he began fathering sons. But exactly when each and every son was born is unknown.

—

A Critique of Form Criticism

By Bible Researcher & Award-Winning Goodreads Author Eli Kittim 🎓

What is Form Criticism?

Form criticism is a discipline of Bible studies that views the Bible as an anthology of conventional stories that were originally transmitted orally and later codified in writing. Therefore, form criticism tries to identify scriptural literary patterns and trace them back to their particular oral tradition. Hermann Gunkel (1862–1932), a German Old Testament Bible scholar, was the founder of form criticism. He was also one of the leading proponents of the “history of religions school,” which employed the methods of historical criticism. While the methods used in *comparative religion* studies were certainly important, these liberal theologians nevertheless began their formal inquiry with the theoretical presupposition that Christianity was equal to all other religions and they, therefore, rejected its claims to absolute truth. However, this underlying presumption involves circular thinking and confirmation bias, which is the habit of interpreting new evidence as confirmation of one's preexisting beliefs or theories. Despite the usefulness of the approach, form criticism involves a great deal of speculation and conjecture, not to mention blatant unbelief. One of its biggest proponents in the twentieth century was German scholar Rudolf Bultmann (1884—1976). Similar to other form-critics who had a bias against supernaturalism, he too believed that the Bible needed to be “demythologized,” that is, divested of its miraculous narratives and mythical elements.

Form criticism is valuable in identifying a text's genre or conventional literary form, such as narrative, poetry, wisdom, or prophecy. It further seeks to find the “Sitz im Leben,” namely, the context in which a text was created, as well as its function and purpose at that time. Recently, form criticism's insistence on oral tradition has gradually lost support in Old Testament studies, even though it’s still widely used in New Testament studies.

Oral Tradition Versus Biblical Inspiration

Advocates of form criticism have suggested that the Evangelists drew upon oral traditions when they composed the New Testament gospels. Thus, form criticism presupposes the existence of earlier oral traditions that influenced later literary writings. Generally speaking, the importance of historical continuity in the way traditions from the past influenced later generations is certainly applicable to literary studies. But in the case of the New Testament, searching for a preexisting oral tradition would obviously contradict its claim of biblical inspiration, namely, that “All Scripture is God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3.16). It would further imply that the evangelists——as well as the epistolary authors, including Paul——were not inspired. Rather, they were simply informed by earlier oral traditions. But this hypothesis would directly contradict an authentic Pauline epistle which claims direct inspiration from God rather than historical continuity or an accumulation of preexisting oral sources. Paul writes in Galatians 1.11-12 (NRSV):

For I want you to know, brothers and sisters,

that the gospel that was proclaimed by me

is not of human origin; for I did not receive it

from a human source, nor was I taught it,

but I received it through a revelation of

Jesus Christ.

Moreover, the gospels were written in Greek. The writers are almost certainly non-Jews who are copying and quoting extensively from the Greek Old Testament, not the Jewish Bible, in order to confirm their revelations. They obviously don’t seem to have a command of the Hebrew language, otherwise they would have written their gospels in Hebrew. And all of them are writing from outside Palestine.

By contrast, the presuppositions of Bible scholarship do not square well with the available evidence. Scholars contend that the oral traditions or the first stories about Jesus began to circulate shortly after his purported death, and that these oral traditions were obviously in Aramaic. But here’s the question. If a real historical figure named Jesus existed in a particular geographical location, which has its own unique language and culture, how did the story about him suddenly get transformed and disseminated in an entirely different language within less than 20 years after his purported death? Furthermore, who are these sophisticated Greek writers who own the rights to the story, as it were, and who pop out of nowhere, circulating the story as if it’s their own, and what is their particular relationship to this Aramaic community? Where did they come from? And what happened to the Aramaic community and their oral traditions? It suddenly disappeared? It sounds like a non sequitur! Given these inconsistencies, why should we even accept that there were Aramaic oral traditions? Given that none of the books of the New Testament were ever written in Palestine, it seems well-nigh impossible that the Aramaic community ever existed.

Besides, if Paul was a Hebrew of Hebrews who studied at the feet of Gamaliel, surely we would expect him to be steeped in the Hebrew language. Yet, even Paul is writing in sophisticated Greek and is trying to confirm his revelations by quoting extensively not from the Hebrew Bible (which we would expect) but from the Septuagint, the Greek Old Testament. Now that doesn’t make any sense at all! Since Paul’s community represents the earliest Christian community that we know of, and since his letters are the earliest known writings about Jesus, we can safely say that the earliest dissemination of the Jesus story comes not from Aramaic oral traditions but from Greek literary sources!

Conclusion

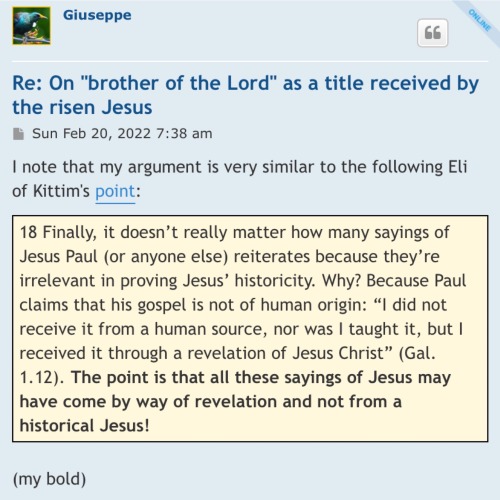

It doesn’t really matter how many sayings of Jesus Paul, or anyone else, reiterates because it’s irrelevant in proving the impact of oral tradition. The point is that all the sayings of Jesus may have come by way of revelation (cf. Gal. 1.11-12; 2 Tim. 3.16)!

And why are the earliest New Testament writings in Greek? That certainly would challenge the Aramaic hypothesis. How did the Aramaic oral tradition suddenly become a Greek literary tradition within less than 20 years after Jesus’ supposed death? That kind of thing just doesn’t happen over night. It’s inexplicable, to say the least.

Moreover, who are these Greek authors who took over the story from the earliest days? And what happened to the alleged Aramaic community? Did it suddenly vanish, leaving no traces behind? It might be akin to the Johannine community that never existed, according to Dr. Hugo Mendez. It therefore sounds like a conspiracy of sorts.

And why aren’t Paul’s letters in Aramaic or Hebrew? By the way, these are the earliest writings on Christianity that we have. They’re written roughly two decades or less after Christ’s alleged death. Which Aramaic oral sources are the Pauline epistles based on? And if so, why the need to quote the Greek Septuagint in order to demonstrate the fulfillment of New Testament Scripture? And why does Paul record his letters in Greek? The Aramaic hypothesis just doesn’t hold up. Nor do the so-called “oral traditions.”

—

💠 Biblical Criticism & History Forum - earlywritings.com (Christian Texts and History) 💠

On the academic website Biblical Criticism & History Forum - earlywritings.com, scholars are quoting Eli Kittim and exploring his thesis that the crucifixion of Christ is a future event!