I Studied The Blade - Tumblr Posts

Secondary German Longsword Guards

Johaness Liechtenauer’s teachings preserved in the Zettel mention that ‘you shall not hold to any position other than solely to the four which will be named here’, in reference to the four main guards, or vier leger, Pflug, Ochs, Vom Tag and Alber. But other sources and fencing masters, particularly later ones, do mention quite a few other secondary guards for longsword. There are some variations and discrepancies between authors of course, as well as different interpretations among contemporary researchers.

Many, if not most of these are considered only transitional guards, so just particular positions while in motion from one to another primary guard or end point of a strike, cut or thrust. In no particular order, these are the ‘other’ longsword guards mentioned in the treatises of the German fencing tradition between approximately 1390 and 1570:

Zornhut - wrathful guard

Langort - longpoint

Mittelhut - middle guard

Wechsel - the changer

Hengetorte - hanging point

Nebenhut - close/side guard

Schlüssel - the key

Einhorn - unicorn

Eisenport - iron door

Brechfenster - breaking window

Schrankhut - barrier guard

Kron - the crown

Zornhut (Wrath)

Zornhut, or Zorn-Hut, is the Wrathful Guard, a left-food forward guard that holds the sword over the rear shoulder so that the flat touches the shoulder and angles slightly backwards, allowing you to deliver powerful ‘wrathful’ strikes. Alternatively the sword can be held slightly above the shoulder and angled back. Typically the sword points down to the floor, though some fechtschule illustrations show it pointing upwards. Even though the Zornhut looks like a variant of Vom Tag, Joachim Meyer tell us that you can do all the techniques from Ochs from Zornhut. Roger Norling mentions that the Zornhut is a guard that can be found in Wilhalm, Erhart, Sollinger, Meyer, Sutor, Verolini and possibly Czynner. Michael Chidester suggests that 16c Germans might have noticed fencers incorrectly ‘chambering’ their sword backwards from Vom Tag to deliver Zornhaw (a powerful cut delivered diagonally downwards from the shoulder), and knowing the the Italians had a similar guard (Posta Di Donna) they decided to just give this position a new guard name in the German fencing tradition. In a contemporary setting if you see people using this guard it’s more often than not Meyer fanboys.

Langort (Longpoint)

Langort, or Lang Ort/Langen Ort, “the noblest and the best ward with the sword” is a point online guard held with the point forward and slightly upward toward the face of the opponent, shown in later German treatises as illustrated above, right foot forward, though earlier masters such as Sigmund Ringeck and Pseudo-Peter Von Danzig indicate that it should be left foot forward: “Before you come too close to him in Zufechten, set your left foot forwards and hold the point towards him with outstretched arms towards the face or the chest.(MS_Germ.Quart.2020_052r)“ Ringeck also specifies that this guard is called the Sprechfenster, if your opponent binds with you, as does, among others, Hans Döbringer, who says that you are standing at the sword with your opponent and that you should feel what he intends. Keith Farrel concludes in this article that to Ringeck then, it seems that the Langort is a position when you have not been bound, and Sprechfenster is when you have been bound, whereas Pseudo-Peter Von Danzig treated the terms Langort and Sprechfenster as more or less interchangeable. As Martin Fabian puts it, Langort is one of the most used positions in longsword fighting nowadays, and for good reason.

Mittelhut (Middle)

In this Middle guard, like the Nebenhut, the blade sits back facing away and behind from oneself with the long edge aimed at the opponent, but raised up to shoulder level with the sword extended in preparation to strike. It can be done on both the left, with right foot forward, and the right side, with left foot forward. It is depicted sometimes as having the point slightly upwards rather than completely horizontally, though according to Mike Cartier the point should slight point to the ground instead. It can be described as both the beginning and the end point of a Mittelhau.

Wechsel (Changer)

Wechsel, or Wechselhut, is known as the Changer, a guard with the hilt next to the abdomen, the point hanging downward to the side at a right angle to the opponent. It is the natural end point for a diagonal full cut through the target, such as the Zornhau. Left Wechsel has right leg forward and the sword on the left side of the body, with the short edge facing forward toward the opponent. Right Wechsel has the left leg forward, sword beside the body, again with the short edge toward the opponent. The Wechsel as a guard is not named explicitly in the earlier sources, but a position that looks like it is shown on several occasions, such as Hans Talhoffer’s Cod. icon. 394a.

Hengetorte (Hanging point)

Hengetorte, or Hangetort, or Hanging Guard, at a glance looks simply like a slightly downwards pointing Ochs guard, but it is used quite differently. Ochs is a threat with the point towards the opponent and prevents attacks on the same side as you have your hands, so an arms-uncrossed Ochs on your left with the right foot forward closes your left opening from attacks, from a right Oberhau for example, whereas the Hangetort, which is typically a displacement rather than a static guard, primarily prevents attacks on the opposite side of your body from where you have your hands, so that same arms-uncrossed with the right foot forward Hangetort points offline to your right, and closes the opening from attacks on your right, from a left Oberhau. In this drill we show both sides of this guard:

In terms of naming conventions, it doesn’t perhaps help that the Ochs guards are also referred to as the two upper Hangers from the Vier Hengen (the right and left Ochs are the Oberhangen, combined with the right and left Pflug, or Underhangen), which are not the same positions as the actual Hanging Guard, since the Four Hangers all point forwards towards the opponent. Inevitably during practice in an English-speaking environment either of these guards ends up being called ‘Hanging’ or ‘Hanger’ which can cause confusion. As far as the present-day popularity of this guard is concerned, just watch this sparring video by Blood & Iron, a hard training and competitively successful group, and count how many times the Hangetort is used to parry overhead strikes, compared with parries with the more traditional Ochs guard for example. It clearly is a very effective position to safely counter from.

Nebenhut (Close/Side)

The Nebenhut, or Close, Side or even Tail Guard, is similar to the Wechsel, with the grip of the weapon at hip height, but with the tip extending back and down. Being an ideal starting point for an Unterhau, the Nebenhut on the left side with the right foot forward is one possible endpoint of a Zornhau/right Oberhau, and the one on the right flank with the left foot forward, that of a left Oberhau. In both cases the long edge faces forward toward the opponent, and the tip of the sword points backwards. Ringeck advises the use of Nebenhut only on the left, because from the right it is not as safe. Jeff Ross suggests in this interesting analysis that there is no historical evidence that the Nebenhut is, as commonly thought, a Tail Guard (like the Italian Posta Di Coda Lunga), but rather that it is actually the same guard as Schrankhut or Eisenport, since several treatises offer essentially identical instructions for a number longsword plays, differing only in the name given to the starting guard involved: Nebenhut in some cases, Schrankhut or Eisenport in the others. Regardless of what the original usage was, I think it’s fair to say that the Nebenhut is generally executed nowadays (perhaps incorrectly?) as a Tail Guard.

Schlüssel (Key)

Jakob Suttor tells us that to be in Schlüssel you stand with ‘your left foot forward and hold your sword with the hilt and hands crossed in front of your chest such that the short edge lies on your left arm and the point stands against the opponent’s face’. A posture from which Meyer describes some plays involving thrusts and cuts, though it does not appear named in earlier sources. There isn’t perhaps an enormous repertoire available from this position, but there are nevertheless some useful techniques and transitions, as Björn Rüther demonstrates in this handy short video.

Einhorn (Unicorn)

Einhorn or Einkiren/Einkhiren is described by Mair as [once you bind with your opponent with the right foot forward], you ‘wind your long edge on his long, drop downward with your short edge at your right side, and step well in towards him in the bind. (…) Then immediately wind around and through, invert your hand and grab around the pommel such that you stand in the Einkhiren and then stab with your point to his face or chest.’ Meyer, once again doing things slightly differently states, ‘strike in powerfully and high at his left ear with the flat or short edge… Thus you force him to go upward rapidly; as soon as he does this, then release your left hand from the pommel, and let your blade snap around in one hand up from below against his right, and plant the point on his chest; meanwhile grab your pommel again… Jab at him thus with reversed hand’. Anders Linnard, in his video description of the Edel Krieg (or Noble War with a reversed grip, one of Ringeck’s counters to Krumphau), shows us a play interpretation which illustrates one of the ways to end up in what I believe to be that Einkleren guard described by Mair:

Though it might resemble Fiore’s Posta Di Bicorno, Brian Kirk in this comparative analysis maintains that the two guards are fundamentally different, as the Einhorn sometimes requires that you actually let go of the sword with the left hand, let the sword rotate in the right hand only, and then re-grip reversed, with the left hand.

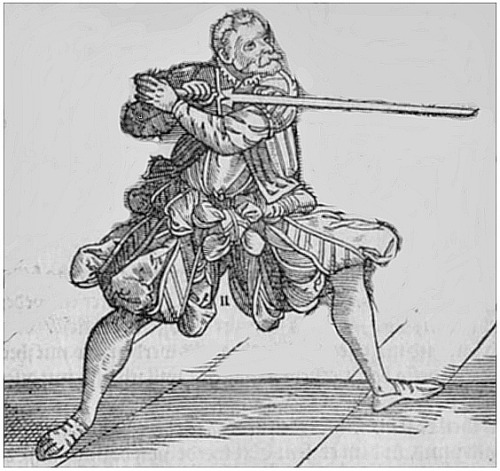

Eisenport (Iron door)

Like some of the other guards, it is worth mentioning that Eisenport, or Eysen Pforte (or eiserin pforte/eyserynen pforten/eysnen pforttn), the Iron Door, exists in two or more variants; with the point upwards, as described by Meyer, or with the point downwards, as described by apparently everyone else. Meyer tells us to stand with our right foot forward, hold our sword with the grip in front of the knee, with straightly hanging arms, so that our point stands upward out at our opponent’s face. He refers to this as the Italian posture Porta Di Ferro [Alta], as illustrated above by Marozzo, and mentions that since thrusting with the sword is abolished among Germans, this guard is not much in use by then. It’s roughly midway between Pflug and Langort.

The other numerous versions of Iron Door in the older German texts are described as a variant of Alber, with the point offline to either the left or the right (halfway between Alber and Wechsel), or in a manner similar to Schrankhut on the right side (or the Italian Tutta Porta di Ferro), with wrists uncrossed and the point offline, or even interchangeably with Nebenhut according to Ringeck. Iron Gate is referred to as ‘the best of all techniques‘ and particularly effective when facing several assailants, more specifically impertinent peasants.

Brechfenster (Breaking window)

Brechfenster or Prechfennster (breaking / speaking window), is, according to Paulus Hector Mair, to ‘stand with your right foot forward and hold your hilt in front of your head such that your thumbs are underneath, with the point high on your right side, and looking at the opponent between the arms’. Mair mentions that if you stand in the Pflug and your opponent throws a Scheitelhau, you can wind up into the Brechfenster so that you are looking out through the arms with the right foot forward, to then drop down and strike in with the half edge to the left ear (zwerchhau). Something similar is shown by Jörg Wilhalm Hutter in Cod.I.6.2º.2_21v. That upwards displacement description sounds a lot like going into Kron, right? In the section on the Schaeitelhau, Mair specifically mentions ‘When he then does the Schaitler to you, displace it with the Kron such that the point and the hilt of your sword both stand above you‘. From what I can tell the difference being that the Kron is an active parry with regular grip, and not a thumb grip like in the Brechfenster, and that the hands are held higher, aside from the fact that the Brechfenster does not require you to necessarily be in contact with the opponents blade. It seems like an unusual longsword guard, but it does appear in contemporary settings (if practicing with minimal gear and aiming for high targets for example, or people that both zwerch and feint a lot). It’s sort of the mid-point between Vom Tag and the end point of a Zwerchhau.

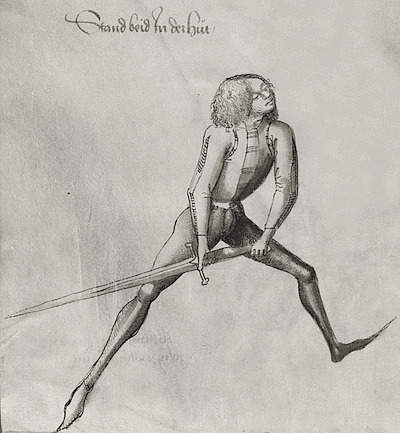

Schrankhut (Barrier)

The Schrankhut, or Schranckhut, is the Barrier Guard, described by Pseudo-Peter Von Danzig on the left side as ‘setting your right foot forward and holding your sword with the point to the ground near your left side with crossed hands such that the short edge of the sword is above and give an opening on your right side’, and on the right it’s ‘standing with your left foot before and holding your sword with the point near your right side on the earth (so that the long edge is above), and giving an opening with the left side’. Several masters consider this guard interchangeable with the not-so-backwards-pointing version of Nebenhut.

Joachim Meyer shows the Schrankhut as a left foot forward Crossed Guard, as seen above, a position with the hands low and forward, with the point forward towards the ground, similar to Hengetorte but with both hands and weapon lower. Meyer also refers to this guard as Eisenport, or Iron Gate, which is a bit interesting considering that elsewhere he refers to Iron Gate as the point-up Porta Di Ferro Alta-looking guard.

Kron (Crown)

In Kron, the sword hilt is held out about head height with the point up. It’s a high parry using the crossguard horizontally, with a regular sword grip. More than an actual guard, Kron is a defensive move in which you lift your sword vertically to catch a descending strike, often described as the best parry against a Scheitelhau, on the cross. Kron is used at the bind and can be a prelude to grappling. The few unequivocal images we have of Kron, like the one above from Ringeck, are always about how to break it with Unterschnitt/Abschneiden, so it doesn’t come across as a position of the utmost interest to the authors.

Some eminent chaps argue the possibility that what we see in Mair and Falkner described as Kron is not the fighter above on the right, but rather the one on the left, with a halbschwert (half-sword) grip against an incoming strike. Contemporary historical fencers certainly use both moves, but in the halls I train in, virtually everyone only calls Kron that parry or bind with the high crossguard forward. I personally call the other half-sword one “Shit, there goes Dave again”.

This post exists mostly because I couldn’t find a comprehensive comparative listing of all these different versions of the non-core Liechtenauer guards online in one place to share with my training partners. Meyer’s terminology in particular is relatively divergent from the earlier sources in the German longsword tradition, but well described and illustrated, so there are quite a few articles exclusively about his works, such as the ones in the Meyer Freifechter Guild, the Meyer Free Scholars Guild and Wiki or even the Scholars of Alcala Meyer study, but for the pre-16th century guys, not so much. There’s ARMA’s basic guards of medieval longsword , which seems maybe a bit outdated, as far as the current understanding of the sources goes, but aside from chapter 4 in Keith Farrel’s German Longsword Study Guide (which is an excellent book btw that you should totally buy), I couldn’t find all of these positions within the German school, ranging from Hans Döbringer to Jakob Suttor, in one single easy-to-access online location. This is almost certainly because it’s quite a pain in the arse to do so. I thought this would be another simple copypasta tumblr job but it’s taken ages, and I’m far from having read, captured, and possibly understood, all the different nuances between sources.

All credit to Wiktenauer for most source images and much of the text, in particular the Jeffrey Forgeng’s Fechtkunst Glossary. The KDF Glossary is another great reference point. None of this is primary research of course, this was learnt in the training hall, or by reading other people’s translations, as well as trolling the forums, particularly HEMAA and Schola. Just like any other interpretation in HEMA, there is (some) room for debate in these. I also realise that the minute I post this someone will share a link to an even more comprehensive and better illustrated guide to German longsword guards, but hey, such is life.

El perro guardian