Naoki Urasawa's Pluto - Tumblr Posts

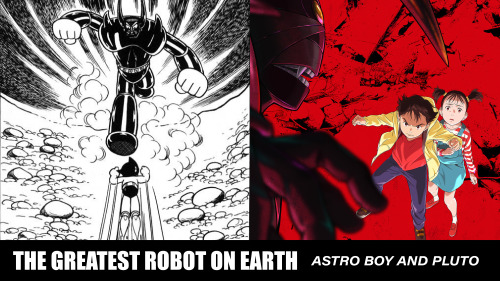

The Greatest Robot on Earth: Astro Boy and Pluto Part I

So you’ve just watched Pluto on Netflix, but you didn’t know that it is the best Astro Boy fanfiction ever made. Great! Or maybe, hypothetically, you’ve read classic Astro Boy but don’t know about Pluto, or, as it was called for the Viz release, Pluto: UrasawaXTezuka. Well, awesome, because I’m about to give you all the details behind their creators and creation and give you a side-by-side of the classic Astro Boy and this new(ish)-fangled Pluto.

C'mon. Look under the read more line. You know you want to.

If you want to skip to the manga side-by-sides, check out part II and part III. Or, you can read the whole thing in one go on Ao3.

Context and Background

Tezuka, Urasawa, and the Showa Era

So, let me start with the basics: What is Astro Boy? What ain’t Astro Boy?

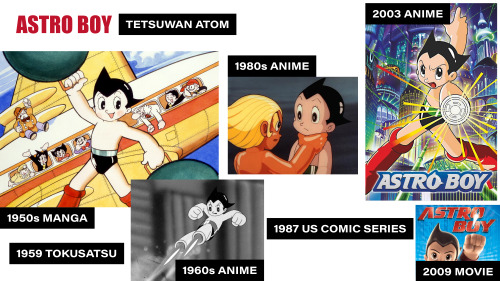

Tetsuwan Atom, known in the west as Astro Boy, is the most well-known manga created by the “Godfather of Manga/God of Manga” Osamu Tezuka in the 1950s, but it metastasized into multiple anime series, games, merch, spin offs of various types, and that one CGI movie in 2009. The series follows the adventures of robot hero Atom (called Astro in the west) as he fights for the benefit of humans and robots to create a harmonious future for both.

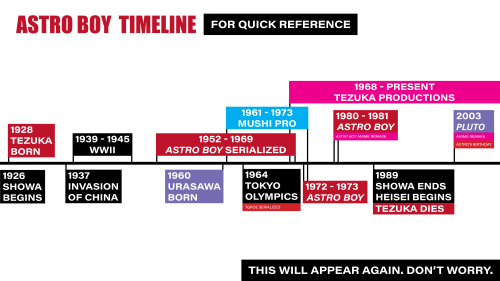

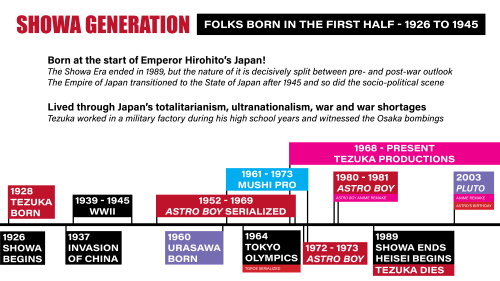

Here’s a timeline of Astro Boy- and Pluto-related events to help you visualize what came out when and why there were multiple runs of the Astro Boy manga. For our purposes, the most important thing to understand is that, even though Astro Boy was a kids’ series, its attitude and themes, as written by Tezuka, reflected the incredible shifts in Japan after World War II and the ever-present shadow of it still left in the minds of its citizens.

But before we get into all that, let’s talk about Osamu Tezuka himself.

Osamu Tezuka's Legacy and His Monster

If you, sweet reader, are a self-appointed weeb and you don’t know the name Osamu Tezuka, I’m personally scandalized. Still, here’s the short version: he was a workaholic mangaka that many hail as the creator of modern shonen manga (historians get heated about when, how, and if Japanese comics made the jump to modern manga, so do your own research, but Astro Boy is definitely the most famous worldwide contender for this title instead of, say, Tezuka’s first work Shin Takarajima/New Treasure Island), and he’s the guy who created the world’s first serialized made-for-TV anime with a sequential plot and sold it as a loss leader to get it on the air.

Arguably, the precedent he set in order to get the anime-ified Astro Boy to screens everywhere is a major reason that the anime industry is so unsustainable, but we’re not here to talk about that.

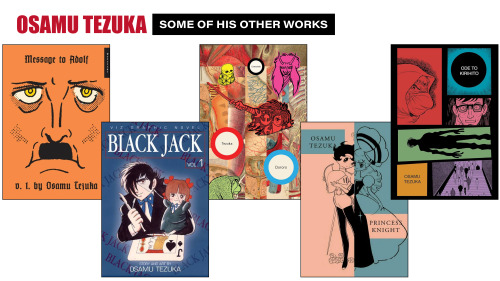

Tezuka-sensei was a prolific, passionate, and deeply beloved artist from Osaka who tackled damn near every manga genre and arguably created some of them before he died of stomach cancer (and overwork, if we’re being honest here.) I’ve only shown a few of the 400-plus titles he created to give a brief overview of the scope of his work. Since I’m talking to you as a fan, not a historian, I specifically chose titles I own or have read most closely.

Message to Adolf, which was also published as Adolf, is about Nazis. Okay, that’s only part of what it’s about, but we’ll revisit this one in more detail later.

Black Jack is probably Tezuka’s second most famous work, and yeah, it’s broadly categorized as a shonen. It follows the adventures of underground doctor and genius surgeon Kuroo Hazama who dresses like a vampire, acts like a black-hearted and preachy douchebag, and endears himself to everyone who interacts with him.

Dororo is a historical fantasy thriller about a guy regaining parts of his sacrificed-upon-his-birth body by slaying demons and uncovering the mysterious past of his companion, the child thief Dororo.

On the flipside, Princess Knight is a shojo for younger kids about a princess with the heart of a boy and the heart of a girl who uses her two hearts to genderbend as needed to maintain her claim over her kingdom and keep it out of the hands of the wicked.

Meanwhile, Ode to Kirihito is an extremely mature medical fantasy drama that questions when and how a person still maintains their humanity and when they become a beast in their own eyes and the eyes of others. As I’m sure you can tell, such themes exploring what humanity means are almost as common to Tezuka’s works as a medical professional featuring as a main character. He needed to use his degree for something, I suppose.

In fact, the common conflict between Tezuka’s bright, young, optimistic, passionate, independently-minded, and opinionated doctor main characters and the corrupt, constricting, slow-moving, old-fashioned medical institution probably offers the most insight as to why Tezuka chose to pursue manga over medicine. I don’t think this was the only reason, but from reading his manga, I feel founded in asserting that the stifling status quo of established medicine was a contributing factor.

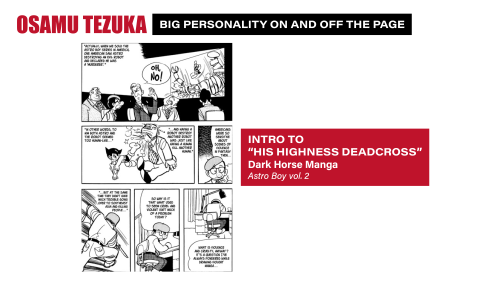

Tezuka never made any bones about putting himself and his feelings directly in his work. He spoke what was on his mind throughout his manga, and his introductions to various Astro Boy stories are no exception. He was also transparent about his struggle to make sure his works maintained popularity even when he resented any changes others suggested he make in pursuit of this goal. In general, Tezuka-sensei didn’t take kindly to the idea of others influencing the direction of his creative visions basically ever, if the story of the Jungle Emperor: Onward, Leo! anime is any indication. (He’s just like me for real.)

If Tezuka-sensei wanted to write about war, he did. If he wanted to write about rape or trauma or abortion or racism, he did. He jumped on the chance to write about sex ed and, well, several of those other topics in Apollo’s Song.

If that scares you, don’t worry. Most of the time, Astro Boy was usually about the nature of war, human rights, the nature of humanity, and robots. It was also written for grade school kids.

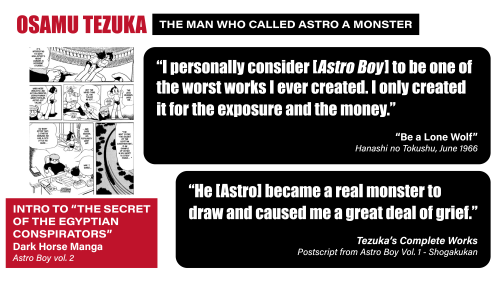

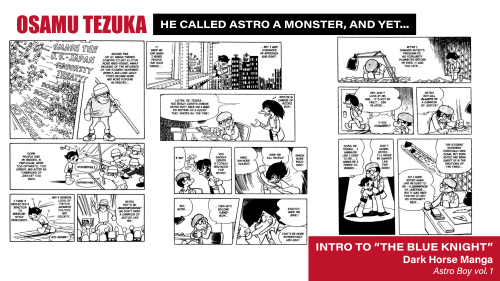

Tezuka’s penchant for frank honesty wasn’t limited to commentary made within his manga, but also about his manga, and his statements on Astro Boy are some of his more standout claims on that front. That he called Atom a “monster” and said he created him “for the exposure and the money” doesn’t paint a flattering picture of his attitude towards his most famous work.

But, in truth, his distaste for compromising the truth of his characters at others’ suggestions probably betrays his real feelings about Atom. As much as he may be Tezuka’s monster, he is also his pure-hearted hero of justice and beloved creation. And, by his own admission, his feelings towards his work during the creation of “The Greatest Robot on Earth”, the Astro Boy story on which Pluto is based, were distinctly positive (even if at one point the background characters remark that Atom is a monster!)

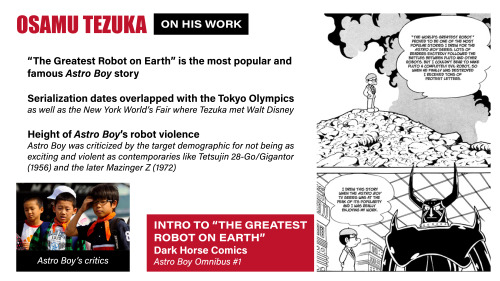

The readership’s opinions on “The Greatest Robot on Earth” were likewise pretty positive. Among those readers was Naoki Urasawa, who credits the story with inspiring his deep love of manga. (His recounting of the impression the story left on him in this interview with Netflix Anime is incredibly sweet.)

Naoki Urasawa and His Monster

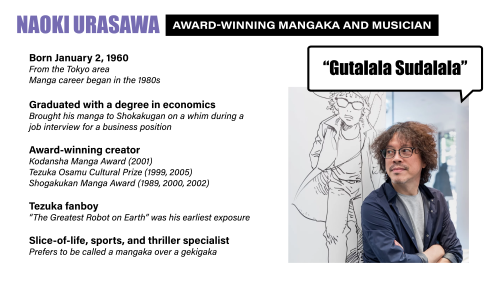

Who is Naoki Urasawa, besides the guy who co-wrote and illustrated the 2003 Pluto manga? Well, Urasawa-sensei is my favorite mangaka, so jot that down, and he’s known for his suspense thrillers, layered narratives, melodramatic showstopper moments, and also stories about cute girls doing sports. He is also a musician and guest professor alongside his editor and Pluto co-writer, Takashi Nagasaki.

20th Century Boys, named in part for a T.Rex song, is arguably his most famous work and it is heavy on the 1960s-1970s nostalgia, but in a good way! The inherent optimism, kindness, hope, and passion (and sometimes outright cheese) of every Urasawa character and title never feels insincere. The series is a seinen with the heart and whimsy of a shonen (and personally, I feel like such a description holds true for even Uraswa’s darker works.)

If you don’t want to read 20th Century Boys or its sequel, 21st Century Boys, you can watch the live-action movie adaptations.

Meanwhile, Monster is my favorite manga and anime. Herr Doktor Tenma (yeah, like Astro Boy’s Tenma), a Japanese brain surgeon practicing in 1980s Germany, saves the life of a little boy only to learn years later that the kid is a mass murderer, his murdering ways continue into his adulthood, and he will likely never be caught. Only Tenma knows the truth, so he embarks on a quest to stop the “monster” he revived.

I have less familiarity with Yawara! and Happy!, but the first is a sports comedy about a girl struggling to balance an athletic career and a normal life, and the second is a sports drama about a girl pursuing tennis to avoid becoming a prostitute.

Pineapple Army is about an ex-merc’s adventures working as a self-defense instructor. Urasawa illustrated this one, but did not write it. I suppose I could have included Billy Bat as a representative work instead, but I honestly didn’t want to start unpacking that—though I will say that Billy Bat is probably the closest answer Urasawa has to Tezuka’s Message to Adolf since they both spin around the concept of a rumor or idea causing the world to lose its collective mind.

So what motivated Urasawa to add Pluto to his body of work? Mostly his editor/producer and co-writer, Takashi Nagasaki, probably. Er, that’s not very flattering. Let me try again.

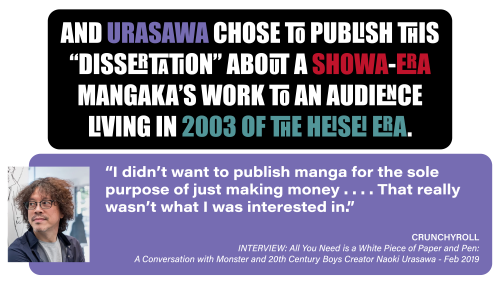

Japanese media loves to emphasize passing its passions and convictions to the new generations (source: have you ever read or watched a mainstream action shonen in your life? If you’ve been paying attention to anything I’ve written about My Hero Academia or read the manga itself, I’m sure you think as much as I do that pointing out such a thing feels like beating a dead horse), and Urasawa’s (and later, the M2 team’s) motivation in creating Pluto is no exception. As Urasawa put it in his Netflix interview, “It’s like we received the baton from Tezuka-sensei, and would pass it on to the new generation."

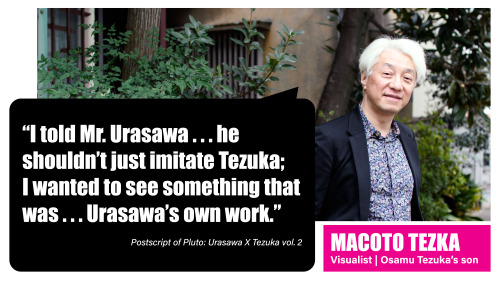

And Osamu Tezuka-sensei’s son, Macoto Tezka (who probably spells his name that way so people don’t get him mixed up with his dad) let Urasawa and Nagasaki do it so long as they made sure the new retelling was something new, exciting, and unique when compared to the original! And while the pressure to succeed in this endeavor probably damn well near killed Urasawa-sensei, I think Tezka made the right call!

But if the goal was to pass on this Astro Boy story, which was written by a REALLY old dude, beloved by kinda-old dudes to the new generation, and practically unheard-of by today’s anklebiters, what kind of direction was the damn thing meant to take?! And why was the answer “fantasy Gulf War Astro Boy fanfiction”?!

Astro Boy in the Eyes of the New Breed

Astro Boy may be a series meant for younger kids, but it didn’t exist in a vacuum separate from the climate of the world from which it came. Tezuka would probably roll over in his grave if it did. The work, its messages, and its sensibilities were grade-A, postwar Showa stuff—particularly its reflections on pacifism, war, and power.

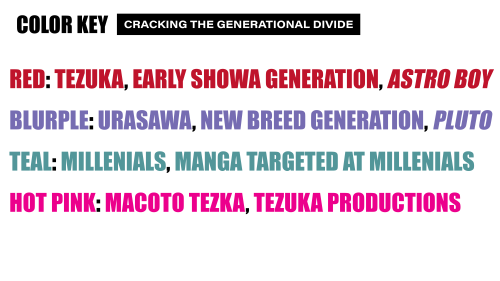

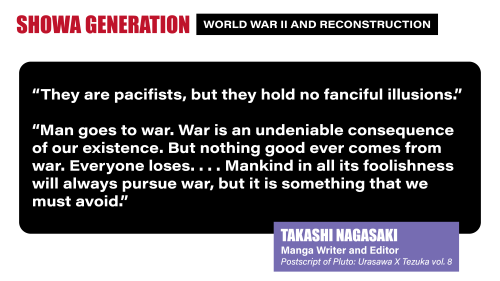

Nagasaki’s summation from the postscript of Pluto: UrasawaXTezuka volume 8 sums up Tezuka and his generation’s outlook pretty handily, but I think it’s helpful to show exemplify this outlook and contrast it with the outlook of Nagasaki and Urasawa’s generation through manga!

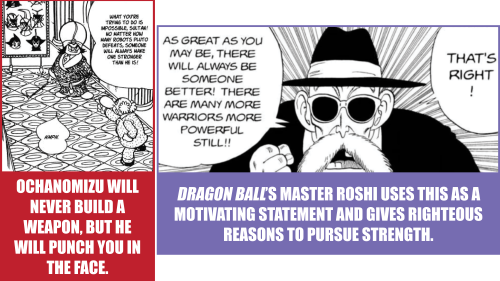

Please observe this key moral-of-the-story panel from “The Greatest Robot on Earth” published in 1964 alongside this panel from late-1980s Dragonball featuring Muten Roshi stating the core idea of his series. I’ve chosen Dragonball as a point of comparison not just because of its notoriety as a big shonen title created for a similar audience as the original Astro Boy, but because creator Akira Toriyama was born in 1955 and, much like his contemporary Urasawa, who was born in 1960, “The Greatest Robot on Earth” left a deep impression on him. (Despite what the caption implies, the photographed page in this tweet actually features Toriyama’s admiration of Tezuka, though I don’t doubt the article from which it is pulled also includes Tezuka’s feelings about Toriyama. I ran it through Google Translate a few times and then laughed when I realized Toriyama made a self-deprecating joke about his poor reading skills, since he points out that he was in third grade when he read “The Greatest Robot on Earth” in the magazine Second Grader.)

To Astro Boy’s Ochanomizu, strength ain’t all that great, and strength for strength’s sake is foolish and vain. In fact, Professor Ochanomizu, who is the moral compass for most Astro Boy adventures, doesn’t value the pursuit of strength the way modern shonen, and several other characters within his own series, do. Hell, he doesn’t give Uran any superpowers even though Atom, the robot boy with nuclear power fueling his 100,000 horsepower (later 1,000,000 horsepower) and seven special powers is her brother!

At the time of Ochanomizu’s creation, real-life Japan still freshly remembered World War II and the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki; no the fuck Ochanomizu (and Tezuka, through him) wasn’t about to endorse or create robots that doubled as weapons. That nonsense was for other, “more violent” robot manga, or the slew of other misguided and corrupt roboticists within the Astro Boy canon. Well, except there was that one time Ochanomizu helped create the artificial sun, but he didn’t ever intend for it to become a weapon.

Meanwhile, while Roshi also does not believe in strength for strength’s sake, he absolutely pursues it and encourages his pupils to do the same while fostering their awareness of the hardship, dangers, and fun of their path. Even with his warning, the Dragonball cast’s pursuit of strength is portrayed as alluring despite the double-edge, much like promoting national pride (and power) increases a nation’s convictions in its unity and identity but also draws the negative attention of other, possibly more powerful nations. Andy Yee succinctly frames this still-impending crossroads about how Japan might use its nationalism—its “pursuit of strength” in Dragonball lingo—in his 2013 article “The Twin Faces of Japanese Nationalism”. In it, he quotes this 2012 Project Syndicate article by Joseph S. Nye, Jr. pointing out that nationalism could be a force for positivity if tempered with reform and control, but could also cause the country to start conflict with its neighbors and shit the bed if left to run wild. (The conversation surrounding the topic of Japanese nationalism continues beyond 1980s manga or the 2013 socio-political scene, of course.)

Unlike Atom or Ochanomizu, Dragonball’s Goku finds such attention alluring: his heart’s desire is to fight strong opponents. It is his ikigai (“reason to live”) and at the end of the Cell Games, it becomes his, uh, shinigai (“reason to die”), if you will.

Did I lose you? I just asserted that the messages in these shonen about acquiring strength = messages about acquiring national pride and power. At its best, the Dragonball-esque attitude towards increasing national pride (and combat strength) is empowering, inspirational, and bolsters the good-hearted. At its worst, it could feed into a cycle of toxicity, unproductive self-importance and, ultimately, flat-out Japanese nationalism and war (and at its stupidest, it just becomes Let’s Fighting Love. Protect my balls.) Since classic Dragonball is a gag manga, I doubt Toriyama was ever thinking this hard about the messages of his work in regards to world history, but that’s sort of the point: Toriyama and his generation likely weren’t thinking this hard about it. Dragonball’s authorship lacks the crushing, firsthand memory of the consequences of unbalanced and misused power that the authorship of Astro Boy has.

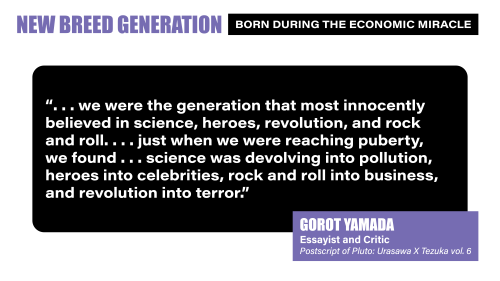

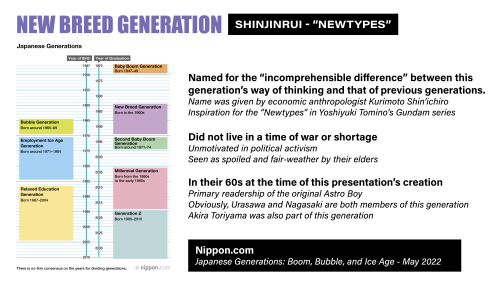

In other words, Astro Boy’s cast pursued scientific advancement while lamenting the inevitable folly and destruction mankind brought forth with it so that Son Goku could fish naked, kick ass, get his ass kicked, meet god, kick ass, ghost god, ghost his family and friends, come back, kick more ass, repeat this cycle like twice, and get everyone to thank him for it. Dragonball’s more optimistic, power-fantasy-ish outlook broadly categorizes the outlook generation of New Breeds (shinjinrui) born around the 1960s like Toriyama, Urasawa, and Nagasaki before the reality introduced in their emerging adulthood hit them like a fucking truck.

The New Breed generation earned its name because their outlook and values, which were developed during a time of economic plenty and peace, seemed totally divorced from the values of the generations that lived during or immediately after World War II.

“They might as well be a different species,” snarked their elders, probably, though not necessarily out of bland hatred—Yoshiyuki Tomino’s Gundam series portrays his Newtypes, who are meant to be at least somewhat analogous to the real-life shinjinrui, in a generally more sympathetic light and occasionally a positive one (if they aren’t being used by someone else, that is.)

Tomino, who was born in 1941, also worked on Astro Boy at Mushi Pro.

Baggage between generations is not unique to any one country, obviously. But in this case, it seems Urasawa and Nagasaki decided to tap into it and incorporate the core beliefs, hopes, and grief of their generation and those of the generations before them into Pluto.

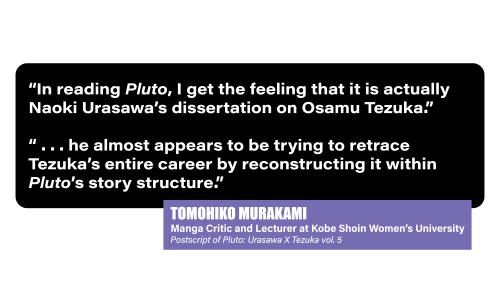

Taking this approach was also the perfect excuse for Urasawa to distill everything he knew and loved about Tezuka’s works into one transformative manga. And don’t just trust Tomohiko Murakami on that—trust me as a fan of both Tezuka and Urasawa. It’s very noticeable that Urasawa and Nagasaki pulled from all things Tezuka to create Pluto even as it incorporated new ideas, including criticism of the Gulf War.

…So it’s probably a good thing I took the time to explain all this stuff to you so that you can now start to see it too! You can thank me later. Let’s see how the classic “The Greatest Robot on Earth” compares to Pluto.

y'all if ai took over in the future i hope it'll be like Pluto <3