Author of “The Little Book of Revelation.” Get your copy now!!https://www.xlibris.com/en/bookstore/bookdetails/597424-the-little-book-of-revelation

447 posts

When Is The End Of The Age?

When is the end of the age?

Eli Kittim

When is the end of the age? Not where, not how, but when? The New King James Version calls this specific time period “the end of the age,” while the King James Version refers to it as “the end of the world.” Biblical scholars often ask whether the end of the age is a reference to the end of the Jewish age, which came to an end with the destruction of the temple in 70 A.D., or whether it’s an allusion to the end of human history. Given that the signs of the times coincide with this particular age, we must examine whether this is literal language, referring to first century Palestine, or figurative, pertaining to the end-times.

Since “the end of the age” is a characteristic theme of the New Testament (NT), let’s look at how Jesus explains it in the parable of the tares in Matthew 13:37-43 (NKJV emphasis added):

“He answered and said to them: ‘He who sows the good seed is the Son of Man. The field is the world, the good seeds are the sons of the kingdom, but the tares are the sons of the wicked one. The enemy who sowed them is the devil, the harvest is the end of the age, and the reapers are the angels. Therefore as the tares are gathered and burned in the fire, so it will be at the end of this age. The Son of Man will send out His angels, and they will gather out of His kingdom all things that offend, and those who practice lawlessness, and will cast them into the furnace of fire. There will be wailing and gnashing of teeth. Then the righteous will shine forth as the sun in the kingdom of their Father. He who has ears to hear, let him hear!’ “

In this parable, the constituent elements of the end of the age are highlighted, namely, the end-times, judgment day, the wicked cast into the lake of fire, and the end of human history. The key phrase that is translated as “the end of the age” comes from the Greek expression συντελείᾳ τοῦ ⸀αἰῶνος. In a similar vein, let’s see how Jesus explains the eschatological dimension of the parable of the dragnet in Matthew 13:47-50 (italics mine):

“Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a dragnet that was cast into the sea and gathered some of every kind, which, when it was full, they drew to shore; and they sat down and gathered the good into vessels, but threw the bad away. So it will be at the end of the age. The angels will come forth, separate the wicked from among the just, and cast them into the furnace of fire. There will be wailing and gnashing of teeth.”

Once again, in this parable, the end of the age (συντελείᾳ τοῦ ⸀αἰῶνος) is described as taking place at the last judgment, when the righteous will be separated from the wicked, while simultaneously placing emphasis on the end of the world, when “there will be wailing and gnashing of teeth.”

Similarly, in Matthew 24:3, the disciples ask Jesus to tell them two things, namely, when will the coming of Christ and the end of the age take place. In comparison to Matthew 24:3, the book of Acts tells us that the apostles asked Jesus if he will restore the kingdom of Israel at the end of the age (Acts 1:6). This question was asked just prior to his ascension and departure. Historically speaking, Israel was restored in the 20th century, which is one of the signs that ties in closely with Jesus’ coming and the end of the age. Jesus responds in v. 7 by saying, “it is not for you to know times or seasons which the Father has put in His own authority.” And v. 9 informs us that Jesus’ response is part of his farewell speech. In like manner, the last recorded words of Jesus in Matthew’s gospel (28:18-20 emphasis added) are as follows:

“All authority has been given to Me in heaven and on earth. Go therefore and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all things that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, even to the end of the age [συντελείας τοῦ ⸀αἰῶνος].”

If Jesus promised to be with the disciples until “the end of the age,” and if that age is a reference to first century Palestine, does this mean that Jesus is no longer with those who have long since outlived their first century counterparts? Taken as a whole, this would also essentially imply that the resurrection of the dead, the rapture, the great tribulation, the lake of fire, judgment day, and the coming of Jesus were events that all took place in Antiquity. Is that a legitimate theologoumenon that captures the eschatology of the NT?

We find an analogous concept in the Septuagint of Daniel 12:1-4 (L.C.L. Brenton translation). Daniel mentions the resurrection of the dead and the great tribulation, but in v. 4 he is commanded to “close the words, and seal the book to the time of the end; until many are taught, and knowledge is increased.” Curiously enough, “the time of the end” in Daniel is the exact same phrase that Jesus uses for “the end of the age” in the NT, namely, καιροῦ συντελείας.

As for the biblical contents, given that the exact same language is employed in all of the parallel passages, it is clear that the end of the age is a future time period that explicitly refers to judgment day, the lake of fire, the harvest, and the consummation of the ages. Obviously, it has nothing to do with the time of Antiquity. Not to mention that the parousia is said to coincide with the end of the current world, when everything will dissolve in a great conflagration (2 Pet. 3:10)!

More Posts from Eli-kittim

Is the Authority of Scripture Biblical?

Eli Kittim

I have a high view of Scripture. But my authority is a Person, not a Book. My authority is God himself, as he reveals to me his will and purpose through spiritual communications. It’s one thing to say that the Bible is “authoritative,” in the sense that it’s reliable and truthful. But it’s quite another thing to say that it’s our highest authority. I think people mistakenly conflate the authority of Scripture with Cessationism, the Calvinist doctrine that spiritual gifts and prophecy ceased with the Apostolic Age. They often cite Jude 1:3 for support. But all that verse says is that “the faith” was revealed to us at some point in human history. It doesn’t say that the Godhead went out of business, took a Sabbatical, or died and left a will. The phrase—“the faith delivered once for all to God's people”—can be disambiguated by examining the context. The other passage cessationists love to quote is 1 Cor. 13:9-10. But all it says is that “we know in part and prophesy in part” because “when the perfect comes, the partial will be done away with.” But not before the complete comes. That’s the key! It doesn’t say that prophecy has ceased. That would be a misinterpretation. Besides, Acts 2:17 says that people in the end times will prophesy and see visions.

Many people are confusing Scripture’s inspiration, revelation, truthfulness, and inerrancy with the concept of “authority,” which the Oxford languages dictionary defines as “the power or right to give orders, make decisions, and enforce obedience.” In short, our highest authority is not the Church, tradition, councils, committees, or even the Bible itself. Our highest authority is Jesus Christ! In Matt. 28:18 (NASB), Christ says:

“All authority in heaven and on earth has

been given to Me”

Where does 2 Tim. 3:14–16 mention the authority of Scripture? It says that “the sacred writings … are able to give you the wisdom that leads to salvation through faith which is in Christ Jesus.” In other words, Scripture gives us wisdom and leads us to salvation which can only be found in Christ Jesus. The fact that Scripture is “inspired” doesn’t mean it represents the final authority. 2 Tim. 3:14–16 reads:

“continue in the things you have learned

and become convinced of, knowing from

whom you have learned them, and that

from childhood you have known the sacred

writings which are able to give you the

wisdom that leads to salvation through faith

which is in Christ Jesus. All Scripture is

inspired by God and beneficial for teaching,

for rebuke, for correction, for training in

righteousness.”

The fact that Scripture is God-breathed (2 Tim. 3:16) doesn’t mean that the Bible has the final say in all matters. The Spirit that inspired the Bible is the ultimate authority on all matters, not the Bible. Scripture itself does not claim to have all authority. Jesus does.

Moreover, the concept of the Sufficiency of Scripture implies that Scripture itself is all we need to interpret Scripture. But Scripture can be interpreted in 30,000 different ways. Just look at all the Protestant denominations that split due to interpretative differences. Thus, Scripture is neither sufficient to interpret itself, nor is it the final authority. Without the Holy Spirit to illuminate us, we will inevitably misinterpret it (Jn 16:13)!

Where does 2 Pet. 1:20–21 mention the authority of Scripture?

“But know this first of all, that no prophecy

of Scripture becomes a matter of

someone’s own interpretation, for no

prophecy was ever made by an act of

human will, but men moved by the Holy

Spirit spoke from God.”

All it says is that prophecy and its interpretation should be revealed by the Holy Spirit, not interpreted by human beings. If anything, it demonstrates the insufficiency of Scripture!

The fact that the Bible contains the Word of God doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s the final authority, or that it’s sufficient in and of itself, so that we don’t need anything else. If the Bible is entirely “sufficient” and adequate for all purposes, we wouldn’t need to be reborn. All we would need to do is read our Bibles. But Scripture cannot save anyone. Jesus does. The Spirit is what we need. We can be saved by the Spirit without the Bible. But we can’t be saved by the Bible without the Spirit.

The Bible does not attest to its own authority. Revelation of the Word does not mean ultimate Authority. The fact that God’s Word is true (Jn 17:17) doesn’t mean that the Bible is the highest authority in our lives. As Christ said, it is the Spirit that perfects us, not the Scriptures (Jn 16:13). Luke 24:49 reads:

“But remain … until you have been clothed

with power from on high”

John 3:5 says categorically and unequivocally:

“unless someone is born of … the

Spirit, he cannot enter the kingdom of God.”

Likewise, Romans 8:9 puts it thusly:

“But if anyone does not have the Spirit of

Christ, he does not belong to Him.”

In John 5:39-40, Jesus demonstrates the insufficiency of Scripture by saying the following:

“You examine the Scriptures because you

think that in them you have eternal life; and

it is those very Scriptures that testify about

Me; and yet you are unwilling to come to Me

so that you may have life.”

When Jesus says that all will be accomplished according to his Word (Matt. 5:18), he’s talking about prophecy, not the authority of Scripture. I’m not suggesting that Scripture errs or is contradictory. Absolutely not! But let’s not confuse the issues. The fact that the Bible contains the Word of God doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s our final authority, or that it’s entirely sufficient. That would be equivalent to Bibliolatry. The Bible is not a paper Pope. Truth and trustworthiness is one thing. Authority is another.

💠 Biblical Criticism & History Forum - earlywritings.com (Christian Texts and History) 💠

On the academic website Biblical Criticism & History Forum - earlywritings.com, scholars are quoting Eli Kittim and exploring his thesis that the crucifixion of Christ is a future event!

What if the Crucifixion of Christ is a Future Event?

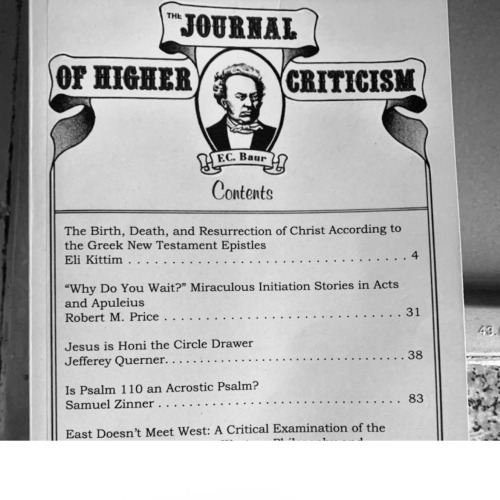

Read the PDF of my article, published in the Journal of Higher Criticism, vol. 13, no. 3 (2018).

Matthew 24:42

Christ, Antichrist, and the Coming Apocalypse