I Didn't Get To Play Video Games That Much During My Youth/teen Years (family Couldn't Really Afford

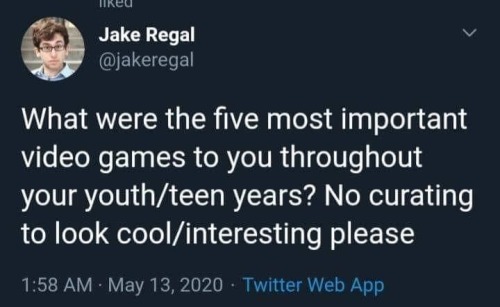

I didn't get to play video games that much during my youth/teen years (family couldn't really afford a game console, and my mom didn't want to get one anyway, so I had to mooch off of my teenage uncle's instead). But here's five anyway, dipping into my early 20s when I was able to buy my own consoles.

Sonic the Hedgehog 2 (youth)

Super Mario Bros. (youth)

Sonic Adventure 2 (20s)

Grandia II (20s)

Final Fantasy IX (20s)

I did most of my video game branching out in my late 20s/throughout my 30s, and honestly my favorites are mostly from that period rather than the early years, but Sonic 2 will forever be one of the more formative games I've played (it was—and still is—my first fandom).

-

yourdudeval liked this · 8 months ago

yourdudeval liked this · 8 months ago -

camellia-salazar liked this · 8 months ago

camellia-salazar liked this · 8 months ago -

saltedcarrots01 liked this · 8 months ago

saltedcarrots01 liked this · 8 months ago -

saffidariya liked this · 9 months ago

saffidariya liked this · 9 months ago -

star-boy-dami reblogged this · 9 months ago

star-boy-dami reblogged this · 9 months ago -

star-boy-dami liked this · 9 months ago

star-boy-dami liked this · 9 months ago -

angelofstarlight liked this · 9 months ago

angelofstarlight liked this · 9 months ago -

audubonii-swift liked this · 9 months ago

audubonii-swift liked this · 9 months ago -

grandearthquakemiracle liked this · 9 months ago

grandearthquakemiracle liked this · 9 months ago -

snoopbii liked this · 9 months ago

snoopbii liked this · 9 months ago -

a-lost-prince reblogged this · 9 months ago

a-lost-prince reblogged this · 9 months ago -

is-casually-a-skeleton liked this · 9 months ago

is-casually-a-skeleton liked this · 9 months ago -

booktiger13 liked this · 9 months ago

booktiger13 liked this · 9 months ago -

wildcat444 liked this · 9 months ago

wildcat444 liked this · 9 months ago -

kriosv reblogged this · 9 months ago

kriosv reblogged this · 9 months ago -

emberpone reblogged this · 9 months ago

emberpone reblogged this · 9 months ago -

spadenade liked this · 9 months ago

spadenade liked this · 9 months ago -

swordshapedleaves liked this · 9 months ago

swordshapedleaves liked this · 9 months ago -

alola03 liked this · 9 months ago

alola03 liked this · 9 months ago -

arckade liked this · 9 months ago

arckade liked this · 9 months ago -

emmaverick liked this · 9 months ago

emmaverick liked this · 9 months ago -

pls-readnowayu liked this · 9 months ago

pls-readnowayu liked this · 9 months ago -

deltervees liked this · 9 months ago

deltervees liked this · 9 months ago -

ouchieismyname liked this · 10 months ago

ouchieismyname liked this · 10 months ago -

neovid reblogged this · 10 months ago

neovid reblogged this · 10 months ago -

marinemas reblogged this · 10 months ago

marinemas reblogged this · 10 months ago -

themusicmansstuff liked this · 10 months ago

themusicmansstuff liked this · 10 months ago -

arcadeofinfinitestardust liked this · 10 months ago

arcadeofinfinitestardust liked this · 10 months ago -

cloudy-osc liked this · 10 months ago

cloudy-osc liked this · 10 months ago -

thatsmydepressiontm reblogged this · 10 months ago

thatsmydepressiontm reblogged this · 10 months ago -

plantb0t liked this · 10 months ago

plantb0t liked this · 10 months ago -

star-shapedfruit reblogged this · 10 months ago

star-shapedfruit reblogged this · 10 months ago -

taliadoesrpgs reblogged this · 10 months ago

taliadoesrpgs reblogged this · 10 months ago -

acerikus reblogged this · 10 months ago

acerikus reblogged this · 10 months ago -

acerikus liked this · 10 months ago

acerikus liked this · 10 months ago -

gamefrog51 reblogged this · 10 months ago

gamefrog51 reblogged this · 10 months ago -

ace1diots reblogged this · 10 months ago

ace1diots reblogged this · 10 months ago -

ace1diots liked this · 10 months ago

ace1diots liked this · 10 months ago -

the-fat-raccoon liked this · 10 months ago

the-fat-raccoon liked this · 10 months ago -

grapemoon reblogged this · 10 months ago

grapemoon reblogged this · 10 months ago -

aryaokayfriend liked this · 10 months ago

aryaokayfriend liked this · 10 months ago -

shy-and-reserved reblogged this · 10 months ago

shy-and-reserved reblogged this · 10 months ago -

i-love-books-because-reasons reblogged this · 10 months ago

i-love-books-because-reasons reblogged this · 10 months ago -

i-love-books-because-reasons liked this · 10 months ago

i-love-books-because-reasons liked this · 10 months ago -

calibricalypso liked this · 10 months ago

calibricalypso liked this · 10 months ago -

json-derulo liked this · 10 months ago

json-derulo liked this · 10 months ago -

heymrverdant reblogged this · 10 months ago

heymrverdant reblogged this · 10 months ago -

a-rti liked this · 10 months ago

a-rti liked this · 10 months ago

More Posts from Kogarashi-art

Writing Tips Pt. 16 - Breaking the Rules

The most important writing tip of all:

Once you know the rules, you can break the rules.

I've seen arguments before asking why someone should even bother learning how to write grammatically "correctly," because "language is constantly evolving and changing." To that, first of all, I would point out that the whole reason we have standardized spelling and grammar to begin with is to make communication easier. It's far easier to understand what someone has written if they follow standard rules of writing so that you don't have to puzzle out what this creative spelling or that jumbled sentence structure is trying to say.

The same goes for standard writing rules, including the tips I've been posting for the past two weeks. Standardized writing styles make things clearer. This is very important with academic works, but is also helpful in literature.

But the thing with literature is that once you know the rules, you can break them for effect. I read a book when I was younger (much younger, not telling you how much, thanks) titled Sink or Swim, about a kid from the city who spent a summer out in a rural area. This book was written somewhat in the style of the kid's journal, and he was an inner-city kid with a distinct writing style based on that. It was...difficult to read at best. The whole thing was written in this kid's dialect, just like I said not to do regarding accents. But the author conveyed the character's voice well, and was consistent, and it really did lend a sense of life to the story, even if I hated it on an entertainment level. On a technical level, it was very well done and deserves credit for that alone.

You need to know the rules first before you can break them. That is why it's important to learn. Once you've learned? Have at it.

I'm just going to add this link to a Reddit post that gives more insight.

Writing Tips Pt. 12 - Purple Prose

Confession time: I like my prose to be a little purple. Poetic description is fun and evocative. So I'm not going to tell you to avoid purple prose entirely.

Unless you're purposely aiming for "minimalist." Then you should avoid it.

Purple prose is writing that is often distractingly ornate and unnecessary for a given writing piece. How much (if any) you should use generally depends on the purpose of the writing piece. Are you writing an academic paper, technical document, or speech? Probably best to avoid purple prose as much as possible.

But fiction is more forgiving. You can get away with some purple in fiction, and poetry is arguably nothing but purple writing.

The important thing is to make sure you're utilizing it correctly.

So here's my advice: don't turn every descriptive sentence into an exercise in just how flowery and ornate you can be. You're trying to tell a story, not show off the biggest words you can find in the thesaurus. By all means, be poetic in describing your setting, your characters, their emotions, etc. Add interest to otherwise routine moments of action. But make sure your writing is still helping to either draw the reader in or move the story along. If your reader is distracted from the point of a section because you were too busy describing every inconsequential tree, you've probably done too much. Use it to set the stage, then simplify.

This is especially important with characters. Descriptions should help your reader visualize your character better. Think of it as painting a portrait of your character. Poetic descriptions can help a reader get an idea of who a character is, but after that, you don't necessarily need to repeat their descriptive traits every time they show up. Trust your readers to remember what your characters look like.

And when you describe your characters, vary up what you describe so that everyone isn't reduced to the same short list of physical traits on repeat. Hair and eye color are important, but they aren't the only features on your character. Give the reader the shape of a jawline, the general build of a body, the angle of a nose, or the line of a neck. Does your character have freckles, blemishes, or a sunburn? Are they stocky and muscular or thin as a rail? Challenge yourself to think of three traits to describe for any given character that aren't hair or eyes.

Finally, be careful how you're describing certain features. If you aren't careful you can easily tread into the realm of silly with your figurative language, especially when you use words that aren't used often (or are used too often, but in amateur writing only) or don't fit the time period. "Tresses" and "locks" are not commonly used for hair, and are more distracting than just calling it "hair," and this is why so many tip lists will strongly advise against "orbs" and "gems" as alternatives for "eyes." It's not romantic or creative, it's distracting.

Unless you're writing Muppet fanfic, I guess. Then you can get away with "orbs."

Writing Tips Pt. 9 - Accents

Here's a more specific one that can really make or break a story: spoken accents.

You've probably all seen it happen in fiction. A character comes from a locale with a thick accent, and the author feels they have to represent it as faithfully as possible, leading to virtually incomprehensible dialogue.

"Ah dinnae ken what ta tell ye, lassie, but the wee scunner'll do ye dirty if ye don' take a firm hand ta him!"

"Sacre bleu, but zis is zimply unnacceptable! We cannot be having ze Rocheforts and ze Garniers zitting in ze zame room or zey will be tearing ze place apart!"

Absolutely awful attempts to render stereotypical accents aside, the above lines aren't very legible thanks to the deliberate mispellings in my attempt to convey sound. And for what gain? How easy is it to tell that the first is an attempt at Scottish, or the second at French?

Best to leave out the bulk of it. Use idioms, turns of phrase, or the general rhythm and structure of the words to convey the accent without leaning so heavily into sound changes. This way, you'll be less likely to shake your reader out of the story because they're too busy trying to puzzle out what someone is saying.

So let's try that again:

"I don't know what to tell you, lassie, but the wee scunner'll do you dirty if you don't take a firm hand to him!"

"Sacre bleu, but this is simply unacceptable! We cannot be having the Rocheforts and the Garniers sitting in the same room or they will be tearing the place apart!"

I left alone a few words that don't have a direct English replacement that keeps the same feel (lassie, wee scunner, sacre bleu), along with one phrase (do you dirty) and the general grammar structure of the second example, but all the stereotypical sounds have been removed. Much easier to read, and yet the general idea of the accent is still there.

By way of personal example, when I was younger, I wrote a story with a character with a very heavy accent that was supposed to be something...I don't know, thick American South?

"Mah name is Daphne. Ah'm a seer. Are ya deaf er somethin'? Ah s'pose ya nevah 'eard of da seers before? Waell, ya 'ave now. I must be 'least tree-undred years old er somethin'. Come in, Ah've been 'spectin' ya. Now, 'ave a seat. Right dere on dat box. Ah don't 'ave much in da furn'ture d'partment. Ya ain't from 'round here, are ya?”

An entire chapter with one character speaking like that. Oof. There were even points where she had to repeat herself and try to enunciate to make it clearer what she was saying to the other characters.

This is not good writing.

So here's an attempt to clean it up while keeping the idea of the accent.

"My name is Daphne. I'm a seer. Are you deaf or somethin'? I suppose you never heard of the seers before? Well, you have now. I must be least three hundred years old or somethin'. Come in, I've been expecting you. Now have a seat, right there on that box. I don't have much in the furniture department. You ain't from around here, are you?"

Much easier to read, and should still get the idea across.

Of course, you can ignore all of this if the incomprehensible accent is part of a joke.

for real, if you see a fic that seems abandoned but you really want to see if it might be completed

i would genuinely suggest not mentioning the fact its abandoned at all. instead, just leave the most effusive comment you can. tell the author specifically what you liked. if they are in a position they might continue it, you might remind them what they liked about the story, and thus maybe revive it.

that is probably your best bet to get a story finished, much more than asking “hey is this abandoned” or asking for it to be continued.

Writing Tips Pt. 11 - Points of View

So tense involves whether a story is narrated in the past, present, or future relative to events. But what about the POV, or point of view? I've seen a lot of confusion about this, especially among novice writers, so I'll try to clarify what they are.

Imagine you're standing in a crowded space, having a conversation with your reader. You're telling them a story, making you the narrator.

If you are the main character of the story, that is First Person POV. You will use "I/me" pronouns.

If your reader is the main character, that is Second Person POV. You will use "you" pronouns.

If one of the other people around you is the main character (not you and not your reader), that is Third Person POV. You will use "he/she/it/they" pronouns.

So the POV is relative to who the main character is.

Obviously, not every first person POV is going to be literally about you. But they will be told as if you, the narrator, are the one experiencing events. The main thing to remember with such stories is that your viewpoint character needs to be interesting or likeable enough to keep the reader's attention. No one is going to want to read an entire story with a flat, boring, or extremely unlikable viewpoint character. It's also easy to get enmired in the character's thoughts a little too much and forget to tell the story.

Of the three POVs, second person is probably the trickiest to write well, and is not normally encountered in fiction, but it isn't completely unheard of. Classic Choose Your Own Adventure books are written in second person to facilitate the conceit that the reader is the one experiencing the story, the main character. The Monster at the End of This Book, The Book With No Pictures, and other similar books for children that have interactive elements also work well, with the narrator or narrating character talking to the reader throughout the story. Self-help books and other articles will frequently use second person POV as well, as does fanfiction that puts the reader in the main character's shoes in order to ship them with a character.

Now, you may have heard of limited and omniscient POVs, specifically for third person. I've heard different ideas of what each of these mean, or how to use them, with a lot of misconceptions, so let's try to clear that up.

Third person limited POV is limited to one character's thoughts and feelings at a time. Think of it as riding in that person's head. You can hear their thoughts, know their feelings, but you don't know what's going on inside any other character's head. You learn what the main character learns, but if someone else is keeping secrets from them, you won't know those secrets. Limited POV is good for drama because it's easier to keep the reader from knowing things they shouldn't. This POV still allows you to use a character's "voice" in the narration, as with first person POV, just with third person pronouns.

Emily scrubbed the dishes with increasing vigor, glaring daggers at John over in the dining room the whole time. It's like he doesn't even care that I'm angry, she thought, dropping another handful of forks into the drain tray with a rattle. Staying out all night, not a word about where he's been or what he's been up to. And who needs that many shipping boxes anyway? Her thoughts spiraled away from her.

With this POV, you can stick with one viewpoint character for an entire work, or you can change as often as needed for the purposes of your story, but it's best to keep such changes at scene and chapter breaks to avoid confusing your readers.

Third person omniscient POV is aware of all characters' thoughts and feelings as needed. Omniscient means "all-knowing." The narrator of this story might tell us what a few characters are feeling, or inform us of a bit of backstory for a newly-introduced character without necessarily riding inside that character's head. Many older works of fiction were written in this style. This is arguably the simplest POV to write, and yet also the easiest to mismanage.

Many authors make the mistake of trying to write third person omniscient by constantly changing which character's head we're in. This is called head-hopping, and can cause literary whiplash for your readers as you keep bouncing around from one character to the next. One way to avoid this pitfall is to avoid getting so deeply into any character's head that you're writing out their actual thoughts. Create more distance between the narrator and the characters.

Emily scrubbed the dishes with increasing vigor, glaring daggers at John over in the dining room the whole time. Her thoughts jumbled about as she mused over where he might have been the night before, where he might have been every night for the past three weeks, and what all those shipping boxes that arrived every day might contain, unaware that John had been meticulously planning a surprise party for her—one that was about to go horribly awry, all thanks to assumptions and lack of communication.

In this example, you can see where I distanced myself from Emily's direct thoughts, so that it wouldn't be as jarring when I also shared John's side of things, along with a little narrative foreknowledge that neither of our characters could conceivably know at this point in time. I am by no means an expert in third person omniscient—I prefer limited for my writing—so I highly recommend checking out guides online for better examples on how to do it right.

One last thing: as with tense, it's important to be consistent, but that doesn't mean you absolutely must stick to one POV for your entire story. Perhaps you want to switch characters periodically, but you want one character's chapters to be in first person POV. Perhaps you want to include letters written between two characters as interlude chapters and thus need to switch to second person. Perhaps one person is literally a deity and thus has a more omniscient viewpoint in their scenes. This is fine, but be consistent within the guidelines you have set for your story. If Emily's scenes are written third person limited, don't switch to first person for one scene.