Writing Tips Pt. 16 - Breaking The Rules

Writing Tips Pt. 16 - Breaking the Rules

The most important writing tip of all:

Once you know the rules, you can break the rules.

I've seen arguments before asking why someone should even bother learning how to write grammatically "correctly," because "language is constantly evolving and changing." To that, first of all, I would point out that the whole reason we have standardized spelling and grammar to begin with is to make communication easier. It's far easier to understand what someone has written if they follow standard rules of writing so that you don't have to puzzle out what this creative spelling or that jumbled sentence structure is trying to say.

The same goes for standard writing rules, including the tips I've been posting for the past two weeks. Standardized writing styles make things clearer. This is very important with academic works, but is also helpful in literature.

But the thing with literature is that once you know the rules, you can break them for effect. I read a book when I was younger (much younger, not telling you how much, thanks) titled Sink or Swim, about a kid from the city who spent a summer out in a rural area. This book was written somewhat in the style of the kid's journal, and he was an inner-city kid with a distinct writing style based on that. It was...difficult to read at best. The whole thing was written in this kid's dialect, just like I said not to do regarding accents. But the author conveyed the character's voice well, and was consistent, and it really did lend a sense of life to the story, even if I hated it on an entertainment level. On a technical level, it was very well done and deserves credit for that alone.

You need to know the rules first before you can break them. That is why it's important to learn. Once you've learned? Have at it.

I'm just going to add this link to a Reddit post that gives more insight.

More Posts from Kogarashi-art

for real, if you see a fic that seems abandoned but you really want to see if it might be completed

i would genuinely suggest not mentioning the fact its abandoned at all. instead, just leave the most effusive comment you can. tell the author specifically what you liked. if they are in a position they might continue it, you might remind them what they liked about the story, and thus maybe revive it.

that is probably your best bet to get a story finished, much more than asking “hey is this abandoned” or asking for it to be continued.

hey hm. can you help me?

im newbie writer. and i know nothing about creating titles and summaries, but i think i can get my way on that. So hm i want to write a muder mystery (just to my friends), the thing is, its all in my head and i cant write it down, besides that i wanna write it in english and im not fluent on it.

Another thing, it's that the plot looks too shitty... Like the murderer is a girl obsessed with her beauty and it's pretty vain, but you know the "murderer" it's to be reveled to much later, and it's too obvious it's her... Oh My what a shame...

----

Start by writing your ideas down (on paper, in a Google Doc, whatever). It doesn't have to be in English if that's not your most fluent language. Organize your thoughts this way. From there, you can try writing it. Don't worry if it seems terrible at first. The best way to improve is to practice. And again, the story doesn't have to be in English if that's not what you're fluent in. Write it in your native language, or whichever language feels most comfortable to you. The story can be translated later (if not by you, then sometimes you can find people online who can do it for you).

And as for how your plot looks, don't worry about that when you're a new writer. Write it anyway. If it's just for your friends, then it doesn't matter as much if it's an idea that's been done thousands of times before, because this is your story, and you can tell it the way you want to tell it.

Writing Tips Pt. 9 - Accents

Here's a more specific one that can really make or break a story: spoken accents.

You've probably all seen it happen in fiction. A character comes from a locale with a thick accent, and the author feels they have to represent it as faithfully as possible, leading to virtually incomprehensible dialogue.

"Ah dinnae ken what ta tell ye, lassie, but the wee scunner'll do ye dirty if ye don' take a firm hand ta him!"

"Sacre bleu, but zis is zimply unnacceptable! We cannot be having ze Rocheforts and ze Garniers zitting in ze zame room or zey will be tearing ze place apart!"

Absolutely awful attempts to render stereotypical accents aside, the above lines aren't very legible thanks to the deliberate mispellings in my attempt to convey sound. And for what gain? How easy is it to tell that the first is an attempt at Scottish, or the second at French?

Best to leave out the bulk of it. Use idioms, turns of phrase, or the general rhythm and structure of the words to convey the accent without leaning so heavily into sound changes. This way, you'll be less likely to shake your reader out of the story because they're too busy trying to puzzle out what someone is saying.

So let's try that again:

"I don't know what to tell you, lassie, but the wee scunner'll do you dirty if you don't take a firm hand to him!"

"Sacre bleu, but this is simply unacceptable! We cannot be having the Rocheforts and the Garniers sitting in the same room or they will be tearing the place apart!"

I left alone a few words that don't have a direct English replacement that keeps the same feel (lassie, wee scunner, sacre bleu), along with one phrase (do you dirty) and the general grammar structure of the second example, but all the stereotypical sounds have been removed. Much easier to read, and yet the general idea of the accent is still there.

By way of personal example, when I was younger, I wrote a story with a character with a very heavy accent that was supposed to be something...I don't know, thick American South?

"Mah name is Daphne. Ah'm a seer. Are ya deaf er somethin'? Ah s'pose ya nevah 'eard of da seers before? Waell, ya 'ave now. I must be 'least tree-undred years old er somethin'. Come in, Ah've been 'spectin' ya. Now, 'ave a seat. Right dere on dat box. Ah don't 'ave much in da furn'ture d'partment. Ya ain't from 'round here, are ya?”

An entire chapter with one character speaking like that. Oof. There were even points where she had to repeat herself and try to enunciate to make it clearer what she was saying to the other characters.

This is not good writing.

So here's an attempt to clean it up while keeping the idea of the accent.

"My name is Daphne. I'm a seer. Are you deaf or somethin'? I suppose you never heard of the seers before? Well, you have now. I must be least three hundred years old or somethin'. Come in, I've been expecting you. Now have a seat, right there on that box. I don't have much in the furniture department. You ain't from around here, are you?"

Much easier to read, and should still get the idea across.

Of course, you can ignore all of this if the incomprehensible accent is part of a joke.

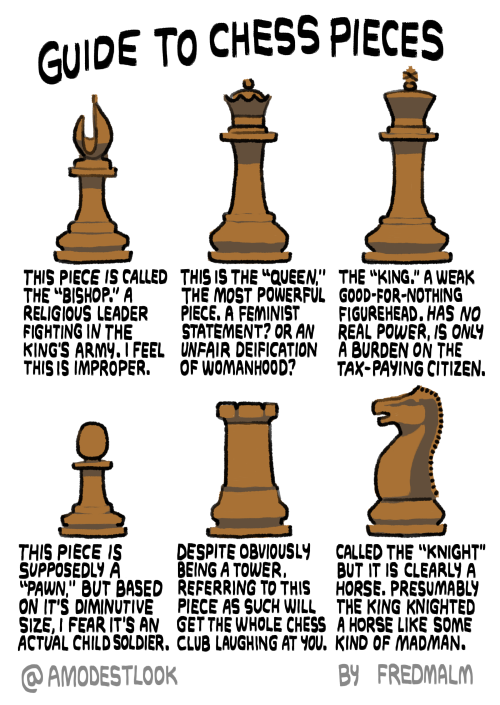

Guide to chess pieces

https://www.patreon.com/fredmalm

Writing Tips Pt. 8 - Show Don't Tell

Ah, the dreaded "Show, don't tell." The answer that gets trotted out in many a discussion when the question of "How do I improve my prose?" comes up. "Oh, but this is prose. Everything is telling!" some might cry (to which I say, "yes, buuuuut...that's not the point"). But none of that's helpful if you don't know what it means.

So let me show you.

First, for your consideration, an example:

Alice was scared. Bob was hunting her, and she feared for her life.

This is telling. We've told the reader that Alice is scared, that she's fearing for her life. That's as plain as the words on the screen. But it feels flat. There's no real depth to it. The reader can't really empathize with Alice, because while they know she's scared, they don't feel that she's scared.

We've told the reader, but we haven't shown the reader.

A brief diversion. The best example I've seen for how to write this actually comes from another Tumblr post, about how to write pain, though it can be applied to anything abstract.

Please go read because it's very good. I'll wait.

Done? Good.

The short of it is this: the post compares writing pain (or anything abstract, really) to drawing an egg, but you aren't given a white pencil, because we already know the egg is white. We need to see how the light hits it and the colors of the shadows and where the table reflects against the shell and the background behind it. Draw around the egg.

So with emotions, you need to write around them. Don't tell us Claire is happy. Show us, by writing the things that convey that happiness. Describe the bounce in her step, the brightness of the sunshine, the warmth in her chest. Show us Frank's heartache in his shortness of breath, the clenching of his heart, his narrowed focus, the muffled sounds around him. Set the mood rather than just telling us what the mood is.

Or consider a screenplay. In movies and television, characters don't just walk out onto the stage and announce, "I'm angry," and then deliver their lines. They stomp. They throw things. They slam doors. Their facial expressions contort. They flail their arms around in huge gestures and raise their voices. But they don't announce their feelings. You can use this in prose by describing the actions of a character to demonstrate how they feel, rather than just announcing their emotion to the reader.

Back to Alice.

Alice's shoulders quivered, skin dripping with sweat, breath coming in short, desperate gasps as she hid behind the couch. Bob's footsteps thundered through the silent house. The slap of the baseball bat in his hand tapped a tattoo against her eardrums. Louder. Closer. Beating in sync with the rapid flutter of her racing heart.

Now, instead of simply telling the reader that Alice is scared, we've pulled them into her world with description and metaphor to convey how being scared feels. The word "scared" doesn't even appear in the new example, but the reader still gets the message quite clearly.

This is how you show.

That's not to say you can never tell. Sometimes you need to. For instance, if your characters are going to have a long discussion about the intricate details of their preparations for a journey, you probably don't need to actually show us every last bit of that conversation. You can summarize it just fine. Or shorten a journey to a few lines if the destination is what matters more.

But for the most part, use your action words, flex your descriptive muscles, and show us what's going on rather than just telling us, especially when it comes to abstract things.