I Played The Cousland Origin, Where The Dog Is Yours To Begin With Rather Than A Dying Hound You Meet

I played the Cousland origin, where the dog is yours to begin with rather than a dying hound you meet later in the prologue. Does that mean my story was a dog and his ghost companions?

What I love about Origins specifically is that all of the main characters are dead.

-

thebinanas liked this · 8 months ago

thebinanas liked this · 8 months ago -

amnememneiae reblogged this · 8 months ago

amnememneiae reblogged this · 8 months ago -

0222199702 liked this · 8 months ago

0222199702 liked this · 8 months ago -

mitskistevens liked this · 8 months ago

mitskistevens liked this · 8 months ago -

chapelofthechimes reblogged this · 8 months ago

chapelofthechimes reblogged this · 8 months ago -

rnolduga liked this · 8 months ago

rnolduga liked this · 8 months ago -

frythefrenchofmcdonalds liked this · 8 months ago

frythefrenchofmcdonalds liked this · 8 months ago -

dammpapaya liked this · 8 months ago

dammpapaya liked this · 8 months ago -

ringsworn liked this · 9 months ago

ringsworn liked this · 9 months ago -

telndas reblogged this · 9 months ago

telndas reblogged this · 9 months ago -

punkrobin reblogged this · 9 months ago

punkrobin reblogged this · 9 months ago -

moonstalk reblogged this · 9 months ago

moonstalk reblogged this · 9 months ago -

lora-loraj reblogged this · 9 months ago

lora-loraj reblogged this · 9 months ago -

lathrine reblogged this · 9 months ago

lathrine reblogged this · 9 months ago -

casually-leviathan liked this · 9 months ago

casually-leviathan liked this · 9 months ago -

caffeinatedsquirrelfood reblogged this · 9 months ago

caffeinatedsquirrelfood reblogged this · 9 months ago -

puttingwingsonwords reblogged this · 9 months ago

puttingwingsonwords reblogged this · 9 months ago -

atracaelum liked this · 9 months ago

atracaelum liked this · 9 months ago -

bardnuts liked this · 9 months ago

bardnuts liked this · 9 months ago -

dr-paine liked this · 9 months ago

dr-paine liked this · 9 months ago -

thesylverlining reblogged this · 9 months ago

thesylverlining reblogged this · 9 months ago -

reapergeeksout reblogged this · 9 months ago

reapergeeksout reblogged this · 9 months ago -

beetlejuice-betelgeuse reblogged this · 9 months ago

beetlejuice-betelgeuse reblogged this · 9 months ago -

beetlejuice-betelgeuse liked this · 9 months ago

beetlejuice-betelgeuse liked this · 9 months ago -

the-morrigxn reblogged this · 9 months ago

the-morrigxn reblogged this · 9 months ago -

ultrakahlannightwing reblogged this · 9 months ago

ultrakahlannightwing reblogged this · 9 months ago -

ultrakahlannightwing liked this · 9 months ago

ultrakahlannightwing liked this · 9 months ago -

javisfreckles reblogged this · 9 months ago

javisfreckles reblogged this · 9 months ago -

javisfreckles liked this · 9 months ago

javisfreckles liked this · 9 months ago -

katzenprince reblogged this · 9 months ago

katzenprince reblogged this · 9 months ago -

jazzmckay reblogged this · 9 months ago

jazzmckay reblogged this · 9 months ago -

likesgohereyeah reblogged this · 9 months ago

likesgohereyeah reblogged this · 9 months ago -

weird-is-good reblogged this · 9 months ago

weird-is-good reblogged this · 9 months ago -

grassmelike liked this · 9 months ago

grassmelike liked this · 9 months ago -

reading-non-stop reblogged this · 9 months ago

reading-non-stop reblogged this · 9 months ago -

asgardianwarrior liked this · 9 months ago

asgardianwarrior liked this · 9 months ago -

whispering-depths reblogged this · 9 months ago

whispering-depths reblogged this · 9 months ago -

queenofcarrotflowers-s liked this · 9 months ago

queenofcarrotflowers-s liked this · 9 months ago -

butchofthewilds reblogged this · 9 months ago

butchofthewilds reblogged this · 9 months ago -

kirbles liked this · 9 months ago

kirbles liked this · 9 months ago -

awatchedfileneverdownloads liked this · 9 months ago

awatchedfileneverdownloads liked this · 9 months ago -

salroka liked this · 9 months ago

salroka liked this · 9 months ago -

amoonenthusiast liked this · 9 months ago

amoonenthusiast liked this · 9 months ago -

agirlwithachakram liked this · 9 months ago

agirlwithachakram liked this · 9 months ago -

shrike-ly liked this · 9 months ago

shrike-ly liked this · 9 months ago -

rexinasuperomnes liked this · 9 months ago

rexinasuperomnes liked this · 9 months ago -

professionalpain liked this · 9 months ago

professionalpain liked this · 9 months ago -

reshiramgirl88 reblogged this · 9 months ago

reshiramgirl88 reblogged this · 9 months ago -

reshiramgirl88 liked this · 9 months ago

reshiramgirl88 liked this · 9 months ago

More Posts from Kogarashi-art

And then you do finally track it down when you realize you had one of the characters wrong.

The true AO3 experience is trying to remember a very specific fic you read some time between 2013 and 2019 but you can only remember two of the characters, a vague idea of the plot outside of one specific scene, and you have no clue what the tags could have been.

This helps for a lot of things. Related is asking someone which of two options you should pick, not so that they can choose for you, but to help you figure out how you feel about it once you're told which one to do. There have been plenty of times I've asked my husband, "A or B?" and he's told me "A," only for me to go, "Great, thanks, I'm choosing B!" It's not because I'm contrary, but because him making the choice for me helped me to realize that I actually wanted B more.

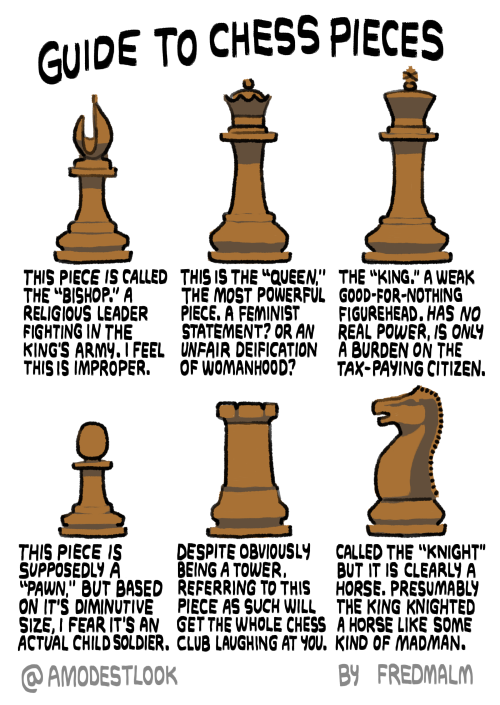

Guide to chess pieces

https://www.patreon.com/fredmalm

Writing Tips Pt. 8 - Show Don't Tell

Ah, the dreaded "Show, don't tell." The answer that gets trotted out in many a discussion when the question of "How do I improve my prose?" comes up. "Oh, but this is prose. Everything is telling!" some might cry (to which I say, "yes, buuuuut...that's not the point"). But none of that's helpful if you don't know what it means.

So let me show you.

First, for your consideration, an example:

Alice was scared. Bob was hunting her, and she feared for her life.

This is telling. We've told the reader that Alice is scared, that she's fearing for her life. That's as plain as the words on the screen. But it feels flat. There's no real depth to it. The reader can't really empathize with Alice, because while they know she's scared, they don't feel that she's scared.

We've told the reader, but we haven't shown the reader.

A brief diversion. The best example I've seen for how to write this actually comes from another Tumblr post, about how to write pain, though it can be applied to anything abstract.

Please go read because it's very good. I'll wait.

Done? Good.

The short of it is this: the post compares writing pain (or anything abstract, really) to drawing an egg, but you aren't given a white pencil, because we already know the egg is white. We need to see how the light hits it and the colors of the shadows and where the table reflects against the shell and the background behind it. Draw around the egg.

So with emotions, you need to write around them. Don't tell us Claire is happy. Show us, by writing the things that convey that happiness. Describe the bounce in her step, the brightness of the sunshine, the warmth in her chest. Show us Frank's heartache in his shortness of breath, the clenching of his heart, his narrowed focus, the muffled sounds around him. Set the mood rather than just telling us what the mood is.

Or consider a screenplay. In movies and television, characters don't just walk out onto the stage and announce, "I'm angry," and then deliver their lines. They stomp. They throw things. They slam doors. Their facial expressions contort. They flail their arms around in huge gestures and raise their voices. But they don't announce their feelings. You can use this in prose by describing the actions of a character to demonstrate how they feel, rather than just announcing their emotion to the reader.

Back to Alice.

Alice's shoulders quivered, skin dripping with sweat, breath coming in short, desperate gasps as she hid behind the couch. Bob's footsteps thundered through the silent house. The slap of the baseball bat in his hand tapped a tattoo against her eardrums. Louder. Closer. Beating in sync with the rapid flutter of her racing heart.

Now, instead of simply telling the reader that Alice is scared, we've pulled them into her world with description and metaphor to convey how being scared feels. The word "scared" doesn't even appear in the new example, but the reader still gets the message quite clearly.

This is how you show.

That's not to say you can never tell. Sometimes you need to. For instance, if your characters are going to have a long discussion about the intricate details of their preparations for a journey, you probably don't need to actually show us every last bit of that conversation. You can summarize it just fine. Or shorten a journey to a few lines if the destination is what matters more.

But for the most part, use your action words, flex your descriptive muscles, and show us what's going on rather than just telling us, especially when it comes to abstract things.