Science Fiction Writing - Tumblr Posts

Space, for writers who can’t be bothered

Space. The final frontier. The inky abyss. The great void. The black. The Big Nothing. What a fantastic playground of opportunity, especially for writers. However, even space has rules.

It's time to clarify some things about space. Too many times I have seen astronomical terms thrown about carelessly in media with no regard for their specific meanings, or space depicted as some fantastical realm where everything is possible.

It’s not.

We’ve spent hundreds of years figuring out how the heavens work, so the least you could do is a bit of googling to make sure that word means what you think it means. I know many writers of space-based fiction are, in fact, space geeks and do respect the laws of physics and the terminology laid forth by experts, and I thank you for that! But for others, here’s a crash course in the fundamentals of space and a few side notes to clear up common misconceptions.

Even if you’re a space-fantasy writer who likes to handwave physics, it’s important to understand what you’re ignoring and what that means for the rest of your world (because physics is an interdependent system- if one thing breaks, everything changes.)

Fundamental Terms

Planet

A planet is a roughly spherical object that does not experience sustained atomic fusion, and usually orbits a star (or, if it’s lucky, more than one star). They are very large compared to humans, and almost never have one single biome. Planets are only spherical, because gravity acts evenly in all directions. Any solid object large enough to be a planet will be spherical, unless engineered otherwise. Engineering otherwise is dangerous, difficult, and not highly recommended. Any irregularly shaped natural object is not a planet, and likely will not have an atmosphere either. Most often these are asteroids or comets.

Asteroid vs Comet

The line between asteroid and comet is fuzzy, yes, but there is a distinct difference. Asteroids are composed of rock and/or metals and do not sublimate (evaporate directly from solid to gas). Comets are composed of ice and maybe some rock, and definitely sublimate. Comets have tails of gas because of this. Bonus misconception factoid: Asteroid and comet fields aren’t even close to crowded, in human scale terms. Objects in the solar asteroid belt are almost always several million kilometers from the other objects, because of Rule 1, and thanks to their relatively small sizes, they’d look like dots at best when viewed from each other’s vicinities.

Star

A star is a large spherical object made of ionized gas that does experience sustained atomic fusion, and that’s why they glow. Stars are best summarized as giant slow-motion nuclear fireballs. They emit energy in the form of radiation, a small slice of which we can see as visible light. A star’s color is strictly dependent on temperature, ranging from red (cool) to blue (super hot) with orange (less cool), yellow (medium), and white-ish (sort of hot) in between. They have very strong magnetic fields, and occasionally small bits of them will violently drift off into space (that is a flare). The terms “star” and “sun” are basically synonymous, but if you want to be nuanced about it, a sun is a star that has planets.

Stellar Death and Supernovae

The death of a star is not fast. It is very, very slow. The star Betelgeuse in the constellation of Orion has been dying (in its red giant phase) for several million years, and isn’t anticipated to explode in its supernova phase for another several thousand. Supernovas themselves are not instantaneous, either; while the inciting core collapse takes just one-fourth of a second, the resulting internal shockwave will take hours to actually break the surface. The expansion of the shockwave takes months. As a dramatic device in storytelling, real supernovae are only useful when you work on extended timescales.

Star system

Star systems are composed of a central star or multiple stars orbiting each other, and occasionally they have planets. Typically, star systems do not exceed more than a lightyear or two in diameter, though complex systems close to galactic centers or in star clusters may have lightyear diameters in the double digits. A good rule of thumb is that the higher the number of stars in a system, the less likely it is to have planets. This is because the gravity interactions will be insanely complicated and the probability of stable orbits is low in complex systems. However, for systems with planets, almost all orbits will be aligned to a single plane, called the ecliptic. Additionally, almost all objects in a system will orbit and spin in the same direction, because the angular momentum from the system’s formation is preserved in its current state. Star systems also tend to be rather spaced out from each other (refer to Rule 1.) The terms “solar system” and “star system” are basically synonymous.

Star cluster

Star clusters are groups of stars numbering between the tens and the thousands that are all loosely bound to each other by their mutual gravity. Stars are generally closer to each other within star clusters than in broader galactic space, which allows radiation to accumulate instead of dissipating in open space. Star clusters typically aren’t very nice places to live if you’re allergic to ionizing radiation (which, incidentally, carbon-based life very much is.)

Galaxy

Galaxies are immense collections of star systems and nebulae, bound together by the combined mutual gravity of every object within them. Small galaxies are composed of hundreds of thousands of star systems, while larger galaxies are composed of billions or even trillions of star systems. Astronomers estimate that the Milky Way, the galaxy in which our star system lies, is composed of three or four hundred billion star systems. Earth’s star system orbits the Milky Way’s center of gravity, the galactic core, at a distance of about 25000 lightyears; just a quarter of the Milky Way galaxy’s estimated total diameter.

Star system vs Galaxy

“Galaxy” and “star system” are not synonymous, not even technically. The scale difference alone should be enough to help differentiate, but it’s also worth restating the nested relationship between the two: galaxies are composed of billions of star systems. Similarly, “intergalactic” and “interstellar” are not synonymous either. “Interstellar” means “between or among star systems.” “Intergalactic,” therefore, means “between or among galaxies.” And as you will see in the next section, the difference is very significant.

Rules

Rule 1: Space is big.

Just absurdly, incomprehensibly, brain-meltingly big. The technical term for it is humungous, or if you want to get really fancy, fuck-off huge. This is why distances between stars are measured in length units equal to the distance that light, the fastest thing in the universe (Rule 2), travels in one metric year. Light may be fast, but space is more than vast enough to make photons into snails.

Planets orbiting within the same star system may be close in the cosmic sense, but on the human scale, they tend to be dishearteningly distant. When the orbits of Earth and Mars bring them closest together (a phenomenon called opposition), they are still 54 million kilometers apart. Radio signals sent between Earth and Mars at opposition have a travel time of about three minutes. At their most separated (401 million kilometers), a signal from Earth would reach Mars in 22 and a half minutes… if the sun wasn’t in the way. Which it is, because it’s the centerpoint of the aforementioned ecliptic plane.

Star systems, as mentioned before, tend to be even more remote from each other. The closest star system to our own, the triple-star system Alpha Centauri, is roughly 4.35 lightyears away. It takes light a good four years and four months or so to get from Alpha Centauri to Earth, but it would take current propulsion technology eons longer to make the trip. The closest known black hole to our star system is 6070 lightyears away in the constellation of Cygnus, which means the radiation we observe from the plasma orbiting it was first flung in our direction right about when Eastern Europe figured out what metal was.

The distance between galaxies is even more vast, and far emptier. The starless abyss between the outskirts of the Andromeda galaxy, the closest major spiral galaxy, and the edge of the Milky Way, our home galaxy, is two and a half million lightyears. The image of the Andromeda galaxy we see when we look at it now is composed of light that left the actual Andromeda galaxy right when our dear Australopithecus ancestors first decided that walking upright was pretty neat.

It’s also worth noting that planets, too, are rather colossal. Even dwarf planets are large in human terms, with the smallest known dwarf planet (Ceres) having a surface area of 2.7 million square kilometers. The entire country of Kazakhstan, population 18 million, is 2.7 million square kilometers. Argentina is roughly the same size, and has a population of just under 45 million. Planet Earth has a surface area of 510 million square kilometers and a population of seven and a half billion, even though over half of the surface is uninhabitable because it’s just liquid water.

When the fate of the world is in the balance, it almost always comes down to one location on the planet’s surface. This is unbelievably illogical. Realistically, planetary-scale warfare would be composed of innumerable smaller conflicts, with no single battle being the sole influence of the war’s tide. The concept of real planetary warfare is horrifying in its vastness, even if planets themselves are relative dust specks in an infinite void.

In short, space is big, and so are the things within it.

Rule 2: Light is the fastest thing in the universe.

The speed of light is just under 300 million meters per second, or just over 670 million miles per hour. Only particles that don’t have mass can move at that speed, because the amount of energy needed to accelerate an object with mass to the speed of light is infinite. In order for something to move faster than the speed of light in real space, it would actually have to have negative mass, which is theoretically impossible for any number of reasons. Please don’t mess with tachyons unless you want all of physics to break.

If you absolutely must get somewhere before a photon does, don’t try to outright break the speed limit. You literally cannot. Instead, try working around it. Make a wormhole, bend space to amplify your speed, move the universe around you, or even take the scenic route through some other dimension we haven’t quite found yet. Breaking the light barrier just won’t work.

Rule 3: Everything in the universe is moving.

If you were to somehow figure out how to entirely stop moving through space, to attain a true velocity of zero relative to an absolutely fixed point in space, it would seem that everything else in the universe just started zipping about at mortifying speeds. This is because the amount of energy in the universe is finite, energy is conserved within matter, and the Big Bang at the start of time had a hell of a lot of energy to dish out. All of this comes to the takeaway that nothing is stationary, ever. Planets move around their stars, stars move around within their galaxies, galaxies move around each other. They all do this dance because of Rule 4.

Rule 4: Gravity is the conductor of the space motion ballet.

Sure you have rocket engines making thrust, and photons carry momentum (that subject is a whole separate lecture), but the ultimate arbiter of motion, even at the speed of light, is gravity. For reasons we still don’t quite understand, objects make dents in three-dimensional spacetime, and these dents affect the way that other objects move. This is why black holes exist, but their name is misleading. Black holes are not two-dimensional holes in space, not even close. They’re so much cooler than that.

Black holes are three-dimensional, spherical objects that are dense enough to bend space to the point where even photons aren’t moving fast enough to escape their gravity. Light moving in the vicinity of black holes is forced to travel in extremely distorted paths, and some may stray too close to the event horizon. The event horizon of a black hole is a sphere-shaped theoretical boundary where the speed an object needs in order to escape the gravitational pull of the black hole is equal to the speed of light.

Rule 5: Inertia can and will liquefy you.

Inertia is the property of objects to resist changing the way they are moving through space. Yes, yes, high school physics, Newton ruined everything for everyone, etc. The difference between moving about on a planet and moving in outer space is that friction does not exist in a vacuum. This is both a blessing and a curse.

Because of Rule 1 (space is big), actually getting anywhere in the cosmos within a reasonable timeframe requires moving at absolutely blistering speeds. Here is where inertia becomes the double edged sword: because there is no friction in a vacuum, getting to the speed you want is no longer a big problem, while slowing down or banking to starboard suddenly is. You can no longer rely on the ground or the atmosphere to do the work for you, which means you spend more energy maneuvering. Another fresh problem is the rate at which you adjust your motion, because humans are fragile meat gundams and inertia is a bitch.

When considering how fast you want something to move, consider first if it has humans (or other lifeforms) on or in it. This will influence how quickly the thing can accelerate, and thus the time it will take for your chosen something to reach the desired speed. Comfortably, humans can accelerate at about ten meters per second squared indefinitely, because this is the gravitational pull of Earth on the surface. Accelerating twice as fast for just as long is a little uncomfortable, but most people would survive it. Any more than fifty meters per second squared of sustained acceleration is pushing it, and 100 meters per second squared is generally the upper limit for acceleration longer than half a minute or so. Please also keep in mind that this also applies to slowing down, as mentioned previously.

Rule 6: Relativity exists, but you can ignore it if you’re sneaky.

More high school physics! This time, Einstein ruins everything by stating that time and space are the same thing, and that Greenwich Mean Time can’t be applied to the whole universe at once. This is founded on Rule 2 (light is the Speediest Gonzalez), and Einstein insisted this rule implies that time is not constant everywhere because humans have a defined frame of reference. However, if you get clever with rule 2, this rule is effectively null and void.

By traveling to a distant point in the universe in a way that’s not technically faster than light but gets you there anyways, you may see yourself leave your point of origin, but that doesn’t change the fact that you already left. It’s just a side effect of you beating an eyeful of photons in a vanity race. Bonus points if you have some sort of instant communication device with which to sync your watches to GMT back home, because that’ll really give ol’ Albert the middle finger.

To Summarize:

Google the terms you use to make sure you’re using them right, or just read this guide

Space has a few universal rules that can’t be responsibly ignored, which are as follows:

Space is big

Light is the fastest thing in existence but also space is big

Everything is moving all the time, through space, which is big

Gravity is why these things move since it’s the only force that acts on a large enough scale to do so, because space is big

Inertia sucks because space is big, but that’s okay because space is big

Relativity also sucks but you can ignore it if you get clever with Rule 2 because space is big

wrote a teaser prologue thingy for a Hyperlanes campaign I want to run, called Orion’s Echo. possibly more parts to come!

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 20.5.5240 // 05:15 Fleet Standard Time

[several seconds of silence]

(quietly) ... I never know how to begin these things, even after twenty years of recording them.

(normal volume) This is Commander Akair Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon, Argo-class capital ship for the Pathfinder Initiative expedition into the Trapezium Cluster. We're currently docked in Palladion Skyharbor, and preparations to leave Athenian orbit are nearly complete. We're scheduled to launch at 0600, bound for 45 Orionis. Our plan is to take the jumpgate routes to Rigel to resupply, then make the jump to Alnilam. From there, we're on our own as we fly into unknown territory.

[beat]

Our fleet is twelve ships strong: the Telamon herself, a support carrier and the capital ship; four Asterion-class exploration frigates, the Archimedes, Pythagoras, Aristarchus, and Eratosthenes; four Hephaestion-class industrial frigates, the Prometheus, Brontes, Arges, and Steropes; two Heraklion-class support frigates, the Balius and Xanthus; and an Asclepion-class medical support corvette, the Dione. I'll admit, when the commission proposed a mere twelve ships for an expedition of such long duration, I was quite skeptical, but in composing the fleet I've grown confident in the crew's capability.

[beat]

Still... I worry. We're going further into the Orion Nebula than anyone ever has, and we don't know what lurks in the dark between the stars. Previous expeditions in the Clouds have described unusual readings from the Trapezium Cluster, hinting at... well, we're not sure. It could be a black hole. Could be a high-arity pulsar, or an exotic star. Or something... organic.

[beat]

I'm overthinking this, I'm sure. We're just going to chart the cluster, gauge its habitability, and set up a jumpgate if possible. But in any case, I'm needed on the bridge again. Commander Vayth, signing off.

[log terminates]

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 24.06.5240 // 18:12 Fleet Standard Time

This is Commander Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon. We are well into day 36 of our voyage, and currently docked with Godalhi Platform A in the Alnilam system for our final resupply. Tomorrow morning, we venture forth into parts unknown. Preparations are almost complete.

[beat]

The crew generally seems to be in high spirits, though anyone can see the apprehension just beneath their cheerful demeanor. I can't say I blame them; I'm just as nervous. Our advance scouts have reported unusual instrument malfunctions, and have confirmed the existence of those unsettling... I suppose the best word for them at the moment would be signals.

[beat]

(quieter)

Most of the crew doesn't know this, but Captain Zuvan of the Aristarchus has had tests run on the signal and they're convinced it's of intelligent origin. They've had no luck on deciphering it yet, but I'm sure they can figure it out. I just hope... (sigh) I don't even know. I hope it's nothing to worry about.

[beat]

I've always harbored a certain fondness -romance, even- for exploring. The unknown has never scared me before. But there's something about this expedition, and our destination, that leaves moths in my gut.

[beat]

I hope I'm wrong.

[beat]

Commander Vayth, signing off.

[log terminates]

wrote a teaser prologue thingy for a Hyperlanes campaign I want to run, called Orion’s Echo. possibly more parts to come!

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 20.5.5240 // 05:15 Fleet Standard Time

[several seconds of silence]

(quietly) ... I never know how to begin these things, even after twenty years of recording them.

(normal volume) This is Commander Akair Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon, Argo-class capital ship for the Pathfinder Initiative expedition into the Trapezium Cluster. We're currently docked in Palladion Skyharbor, and preparations to leave Athenian orbit are nearly complete. We're scheduled to launch at 0600, bound for 45 Orionis. Our plan is to take the jumpgate routes to Rigel to resupply, then make the jump to Alnilam. From there, we're on our own as we fly into unknown territory.

[beat]

Our fleet is twelve ships strong: the Telamon herself, a support carrier and the capital ship; four Asterion-class exploration frigates, the Archimedes, Pythagoras, Aristarchus, and Eratosthenes; four Hephaestion-class industrial frigates, the Prometheus, Brontes, Arges, and Steropes; two Heraklion-class support frigates, the Balius and Xanthus; and an Asclepion-class medical support corvette, the Dione. I'll admit, when the commission proposed a mere twelve ships for an expedition of such long duration, I was quite skeptical, but in composing the fleet I've grown confident in the crew's capability.

[beat]

Still... I worry. We're going further into the Orion Nebula than anyone ever has, and we don't know what lurks in the dark between the stars. Previous expeditions in the Clouds have described unusual readings from the Trapezium Cluster, hinting at... well, we're not sure. It could be a black hole. Could be a high-arity pulsar, or an exotic star. Or something... organic.

[beat]

I'm overthinking this, I'm sure. We're just going to chart the cluster, gauge its habitability, and set up a jumpgate if possible. But in any case, I'm needed on the bridge again. Commander Vayth, signing off.

[log terminates]

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 06.11.5242 // 02:12 Fleet Standard Time

This is Commander Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon. We’ve recently ticked over into day 900 of our voyage, and we are approaching the center of the Trapezium Cluster. As I mentioned in my log on day 648, our scientific complement verified the long-standing idea of a central black hole within the cluster, and it has been the focus of our telescopes for most of this time. After surveying the major stars, we’ve decided to investigate the object. All hands are on deck, pulling round-the-clock shifts to maintain peak performance of the Fleet. We’ll soon be entering its orbit.

[beat]

(quieter) There’s more. Zuvan managed to crack the encryption of the signal themself. All it says is “She wakes,” over and over... and the signal has been getting stronger as we approach the singularity. Whatever it means, whoever she is... the signal is coming from the black hole, or something orbiting it.

[beat]

This is wrong. This is all so wrong. As we fly closer to the source, my mind... it feels... hazy. Like I’m half awake, still almost dreaming... echoes of another time... memory like stardust dripping from a comet... And something else, a presence filling the void...

[brief beat]

(sudden dread) We shouldn’t have come here.

[bolting to his feet]

(shouting away from the mic) BARO! TURN THE FLEET AROUND, SOMETHING IS OUT THERE! IT’S–

[monumental crash, log terminates]

wrote a teaser prologue thingy for a Hyperlanes campaign I want to run, called Orion’s Echo. possibly more parts to come!

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 20.5.5240 // 05:15 Fleet Standard Time

[several seconds of silence]

(quietly) ... I never know how to begin these things, even after twenty years of recording them.

(normal volume) This is Commander Akair Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon, Argo-class capital ship for the Pathfinder Initiative expedition into the Trapezium Cluster. We're currently docked in Palladion Skyharbor, and preparations to leave Athenian orbit are nearly complete. We're scheduled to launch at 0600, bound for 45 Orionis. Our plan is to take the jumpgate routes to Rigel to resupply, then make the jump to Alnilam. From there, we're on our own as we fly into unknown territory.

[beat]

Our fleet is twelve ships strong: the Telamon herself, a support carrier and the capital ship; four Asterion-class exploration frigates, the Archimedes, Pythagoras, Aristarchus, and Eratosthenes; four Hephaestion-class industrial frigates, the Prometheus, Brontes, Arges, and Steropes; two Heraklion-class support frigates, the Balius and Xanthus; and an Asclepion-class medical support corvette, the Dione. I'll admit, when the commission proposed a mere twelve ships for an expedition of such long duration, I was quite skeptical, but in composing the fleet I've grown confident in the crew's capability.

[beat]

Still... I worry. We're going further into the Orion Nebula than anyone ever has, and we don't know what lurks in the dark between the stars. Previous expeditions in the Clouds have described unusual readings from the Trapezium Cluster, hinting at... well, we're not sure. It could be a black hole. Could be a high-arity pulsar, or an exotic star. Or something... organic.

[beat]

I'm overthinking this, I'm sure. We're just going to chart the cluster, gauge its habitability, and set up a jumpgate if possible. But in any case, I'm needed on the bridge again. Commander Vayth, signing off.

[log terminates]

SOS Transponder // Pathfinder Telamon // 05.01.5244 // 00:06 Fleet Standard Time

(weary, broken) This is... (sigh) Stars above, I just don’t know what to say.

[beat]

I’m stranded on a cold, lifeless desert moon without a name. This planet’s sun is like a dark, angry eye, glaring down at me. At night, the sky shines with violet clouds. I think the word for it is nebula. ...I’m alone. Nobody else lives on this world, as far as I know.

[beat]

(sigh) Judging by the wreckage, I must have crashed, though I only have the vaguest notion of how long ago that happened.

...Months? ...Years?

The remnants of the hull are intact enough for me to read the name Telamon. I feel like I should know what that means, but I don’t. Most of the systems on the ship are destroyed beyond repair, at least as far as I can tell. I feel like I used to know how to fix these things, but that’s all gone... The only system still in working order, besides life support, is... this. Whatever this is. Some sort of communicator, I think.

[beat]

...I hope.

[beat]

(more broken) If anyone out there is listening, please come find me. Or at least send some sort of reply. I need help, however you can help, please just... help me. I don’t know where I am, or how I got here. But worst of all...

(wavering) I don’t know who I am.

[transmission terminates]

wrote a teaser prologue thingy for a Hyperlanes campaign I want to run, called Orion’s Echo. possibly more parts to come!

Captain's Log // Pathfinder Telamon // 20.5.5240 // 05:15 Fleet Standard Time

[several seconds of silence]

(quietly) ... I never know how to begin these things, even after twenty years of recording them.

(normal volume) This is Commander Akair Vayth of the Pathfinder Telamon, Argo-class capital ship for the Pathfinder Initiative expedition into the Trapezium Cluster. We're currently docked in Palladion Skyharbor, and preparations to leave Athenian orbit are nearly complete. We're scheduled to launch at 0600, bound for 45 Orionis. Our plan is to take the jumpgate routes to Rigel to resupply, then make the jump to Alnilam. From there, we're on our own as we fly into unknown territory.

[beat]

Our fleet is twelve ships strong: the Telamon herself, a support carrier and the capital ship; four Asterion-class exploration frigates, the Archimedes, Pythagoras, Aristarchus, and Eratosthenes; four Hephaestion-class industrial frigates, the Prometheus, Brontes, Arges, and Steropes; two Heraklion-class support frigates, the Balius and Xanthus; and an Asclepion-class medical support corvette, the Dione. I'll admit, when the commission proposed a mere twelve ships for an expedition of such long duration, I was quite skeptical, but in composing the fleet I've grown confident in the crew's capability.

[beat]

Still... I worry. We're going further into the Orion Nebula than anyone ever has, and we don't know what lurks in the dark between the stars. Previous expeditions in the Clouds have described unusual readings from the Trapezium Cluster, hinting at... well, we're not sure. It could be a black hole. Could be a high-arity pulsar, or an exotic star. Or something... organic.

[beat]

I'm overthinking this, I'm sure. We're just going to chart the cluster, gauge its habitability, and set up a jumpgate if possible. But in any case, I'm needed on the bridge again. Commander Vayth, signing off.

[log terminates]

hey folks, I wrote a thing and I’m proud of it! it’s a short sad story about a man dying alone in deep space. check it out!

There’s no sound in space.

Everyone knows this. Every child born on a spacefaring world is taught that the vacuum of space, having only a few atoms per cubic centimeter, cannot by its nature conduct acoustic waves. This means that whatever sounds you hear while plying the void between worlds come from within your own spacecraft.

Some take solace in this fact, enjoying the silence and solitude that the endless deep embodies. Some prefer to bask in the bone-deep humming of the drive coils, pulsing their magnetic hymns of atomic power; or keep time by the steady, quiet chirps of the scanners watching the endless night all around.

But when the hull starts to whisper as you lie awake in your berth, singing your sins to you like a lullaby for the damned… the only way to escape it is to throw yourself out of the airlock.

For there’s no sound in space, and no one can hear you scream.

oh right! I wrote another short piece set in the Diaspora the other day: Out of the Cradle [link], a story about the first words spoken on Mars.

Ancient Mother Earth, cradle of the human miracle yet half-forgotten by her long-departed children, appears in the 53rd century as an overgrown playground of gods. Vast and awesome constructs, in various stages of disrepair, dot the slowly-healing landscape and the orbits above, evoking an image of toys left scattered on a bedroom floor. The human race once longed to spread its wings and fly to the stars, and Earth now remains the empty nest from whence they fledged.

Yet, she is not all empty, after all. Some could not bear to leave their mother behind, and for millennia now they have toiled in quiet solace to care for the weary Earth after her labors to birth starfaring humanity. And, much as one turns to the halcyon of childhood to comfort the grief of adulthood, so too does humankind their Earthbound infancy: now, slowly, a tide of reverent hiraeth sweeps across the people of the stars, drawing them back to the garden.

Mother is calling her children home.

Awakening

Voices.

That was the first thing I was aware of, breaking through the tranquil oblivion like a stone cast into a still pool. Someone was speaking, though I couldn't make out what was being said. It sounded distant, as if a league of water separated us. Grasping weakly at consciousness, I tried to call out, to stir...

And the second thing I became aware of was the pain.

I became reacquainted with my body as a dull ache spread through it, starting with my head and making its way down my core and out to my limbs. The ache gradually intensified as the moments dripped by, as did the voices. Though still muffled, as my sentience returned to me I realized I could neither recognize nor understand them. Still unable to move, I found the only muscles that would respond to me were my eyelids. I opened them, eager to test another sense.

I saw nothing at all, just the same oppressive, featureless darkness. The only thing that changed was some sort of cold fluid now pressing against my exposed corneas. I panicked for a fraction of a second, suddenly afraid of drowning, before realizing I was still breathing. As tactile sense surfaced above the omnipresent ache, I became aware of a breathing mask over my face, as well as IV feeds in my arms and electrodes all over my body. What was all that about…?

It occurred to me then that I did not know where I was. The first coherent internal dialog I produced was a simple ‘oh no,’ as my heart began to pick up its pace. The last thing I remembered… I was on a vast ship, bound for a distant star, never to return. Had we arrived at long last?

A loud, beeping alarm startled me. Despite the pain, confusion, and weakness suffusing every fiber of my being, at last I began to stir. So too did my surroundings: there was a quiet rumble and an accompanying hiss as the frigid fluid started to drain. The voices changed cadence, evidently surprised, and got louder- no, closer.

Though the light was dim, it nearly blinded me as the cover of my stasis chamber was lifted open. I squinted at the shapes attached to the voices; they were blurry and indistinct. One of them leaned closer, and I was able to resolve some features. Long, white hair, elegant feminine facial structure, piercing golden eyes. A pair of shapes loomed just behind them, large and white and triangular. Feathered. Were those… wings?

The person said something- a question I couldn't understand. They gently removed the breathing mask. I coughed at the first taste of stale, cold air, and the pain flared in my chest, threatening to shake my grasp on the waking world. The stranger touched my face with delicate grace, concern apparent on their own. I was struck by a thought.

“Are… you… an angel?” I managed to gasp, weakly.

My savior frowned, and said something else that was lost on me. The other voice, from somewhere outside my field of vision, gave a reply that seemed to disappoint them. I understood only one word, a name I vaguely recalled from somewhere in ancient mythology: “Mnemosyne.” The winged being nodded, and placed the mask back over my mouth and nose. Before I could protest, they placed some sort of device against my forehead, and I sunk back into dreamless nothing.

When I awoke again, a different voice greeted me -one I could understand, this time.

“Hello, friend,” it said. It was soft, pleasant… welcoming.

I opened my eyes, but the light was too bright, and I shut them quickly.

“Please, take your time adjusting to the burden of consciousness; you have been in stasis for a very long time.”

Stasis. Yes. Now that I was awake, we must have reached our destination. I noted, with relief, that the all-consuming ache was no longer all-consuming. The air was warm, and fresh. I opened my eyes very slightly, letting them acclimate to the revival room.

“That’s it, ease into the heat and light,” the voice encouraged me. “There we go.”

After several minutes, I felt able to look around. I sat up, slowly, carefully, and looked for the source of the voice. To my great surprise, I was not in the revival room… or at least, not one that I recognized. The room was small, clean, and colored in gentle pastels. I was further shocked to discover that the voice was that of a friendly-looking robot, humanoid in shape, holding some sort of electronic tablet.

“Hello!” they said, and smiled. Their smile, amazingly, was somehow reassuring. “I am Mnemosyne, your post-stasis bedside attendant.”

“H-hello…?” I managed. “What… what is… where am I?”

“Ah, let me get you up to speed. Welcome to the fifty-third century of what you most likely know as the Common Era.”

I blinked, failing to grasp the meaning of the sentence. “The what?”

Mnemosyne continued. “Oh yes, it has been some time indeed, but please save all your questions for the end of this orientation. According to your chart, you have missed…” They glanced at the information on the pad. “...approximately three thousand and twenty-four years of intervening time.” They paused, and a look of concern crossed their artificial face.

“Oh dear. You should probably lie back down for this.”

Alone Together

Every now and then, someone will ask, "why is it still called first contact?" They think they are clever, apparently, by pointing out that we already know intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, and so it should simply be called 'contact.'

But it is clear that they do not understand the weight these words carry.

Far back in 2145, humankind made first contact on a small, airless, inner moon of Uranus. Except... no one was there to greet us. All we found were the remains. Within a week, our understanding of life in the universe had gone from hopeful optimism to somber concern: had we really been so close to contact, only for our elder and only counterparts to vanish? Research on the ruins revealed that the ancient starfarers had wiped themselves out in a catastrophic civil conflict, and we feared what that meant for us. We resolved, then, that we would do better, not only for ourselves but for the ones who had come before us and lost their way. We had given up one kind of loneliness -that of simple ignorance- for another, far worse kind of loneliness: that of the sole survivor.

Our loneliness was not to last, fortunately. In 2191, the crew of the Arete mission to Proxima Centauri encountered a species of lifeform on the frigid moon Calypso which exhibited unusual intelligence, and in time discovered the great settlements they inhabited. After two years of study, the Arete explorers established rudimentary two-way communication with the Calypsians and grew a conversational relationship with the people of one nearby settlement. Humankind was overjoyed: here, at last, were the interstellar neighbors we had longed for.

But eventually the Arete mission had to return to Earth, and the Calypsians would not achieve interstellar radio transmission for a hundred more years. Even once they were able to commune with us across the great void, we found that our species were too different to have much in common aside from scientific interest. Thus, we were faced once more with a new and uniquely tragic kind of loneliness -almost that of estranged cousins.

In 2220, our prayers seemed to be answered at last by a stray radio signal from Tau Ceti. Though it took time, we were able to decipher its meaning and sent a return message, followed by a probe. The initial course of contact was slow, as is always the case with remote contact from across the emptiness. Over patient years of interaction, we learned how to communicate with the skae, and eventually sent a crewed mission to their homeworld of Ra'na: Andromeda One, the first of many.

We discovered the skae were a younger civilization than us, by several centuries, and so took responsibility for teaching them to be more like us. We taught them the secrets of nature and technology that they had not yet uncovered- of black holes and quarks, of the microchip and the fusion reactor. They accepted our gifts with wonder and gratitude, and in turn taught us their ways of terraformation- new methods to accelerate the healing of our own world and transform others from dead waste to bountiful gardens. Together we founded a coalition, to unite all civilizations seeking starflight under the common purposes of curiosity and betterment. But although this was everything humanity had ever wanted, we still felt the pangs of loneliness: the burden of the elder and mentor.

It was our good fortune, then, that elder civilizations were watching us. Just a decade after founding the USSC, Earth received a radio message from the star Epsilon Indi. It was a direct greeting, excited and hopeful. "We are shyxaure of Delvasi and ziirpu of Virvv. We saw you," they said, "and you have done well. We have ached to reach out for centuries, but worried over what would follow if we did. The alliance you have forged with the people of Tau Ceti is assurance that we are, truly, alike in thought. We are proud to call you neighbors, and hope to soon call you friends."

While we waited for their embassy ship to arrive as promised, humanity reveled in passing a test we had not known was ongoing. We had proven ourselves worthy of contact, worthy of inclusion into the interstellar community... and yet, a new loneliness seeped through the cracks of our joy. We had anguished in isolation for so long, all the while our cosmic seniors watched from not so far away. For hundreds of years, we had not realized there were new friends just beyond the horizon. And so, in secret, we mourned this loneliness: that of what could have been.

In the centuries that have followed we have discovered even more sapient beings around us: the rimor of the Eridani Network, the Xib Zjhar of Xiilu Qam, the pluunima of Niima. We are connected to each other in many ways, but the most important of these is simply that we share the gift of sapience. In this vast and quiet universe, any fellow intelligence is infinitely precious because we are the only ones, as far as we know. Every contact event is first contact, all over again, because every new civilization that we encounter will expand our horizons just enough for us to wonder: "was that last contact? Is there still someone else out there, or is that the end of roll call? Are we alone together, now?"

This, the grandest and most poignant of all mysteries, is why the motto of the Coalition is "solum habemus invicem et stellas" – "we only have each other and the stars."

I'm starting to come back around to Astra Planeta in a really substantial way, and if you don't mind I'm gonna think out loud here for a little.

Astra Planeta is categorically hard science fiction, in that it adheres to the definition of the genre: the scientific and technological elements presented in the world's canon are within the realm of what we consider possible with our current collective knowledge of science and technology. However, ASP breaks the mold of hard science fiction by being optimistic in three key ways: technological, social, and existential.

Astra Planeta is technologically optimistic in assuming that any engineering problem standing between us and efficient interstellar travel can be solved. According to the canon timeline, fusion power is relatively commonplace by the mid-21st century, and by the start of the 22nd century humanity have developed a proper torchship. Human health issues stemming from long-term space travel are easily resolved with high-power magnetic shielding and centripetal pseudo-gravity, plus a touch of good ol' genetic therapy to keep the body strong and healthy. Wormhole technology is developed for instantaneous communication by the 22nd century, and by the end of the 23rd century humans have begun to unlock faster-than-light travel by engineering our first warp drive. In the few centuries between the first spaceflight and the first extrasolar mission, humans figure out (non-cryogenic) stasis, perfect closed-system environment maintenance, and build AI with thought patterns so similar to people they might as well have souls. We have our cake and eat it too. All of this is within the scope of "scientifically possible," though certain parts are hotly debated in academic circle. But the rapidity with which we achieve these milestones is shamelessly optimistic. It has to be, or else the premise of the setting falls apart.

Astra Planeta is socially optimistic in assuming that humanity, as a global entity, can overcome -or at least overlook- the cultural divisions which set people apart and cooperate as a singular civilization. I've talked about this extensively elsewhere, but one of the keystones of the project is the thorough demilitarization of planet Earth and all her nations. By the end of the 21st century, "war" is a word that has passed out of the news cycle and into history books. It took some doing, sure, but in this reality humankind was faced with the imminent degradation of their home planet and collectively decided that there were bigger fish to fry than each other. Complex issues left unresolved for generations were gradually untangled and sorted out, with a lot of patience and a bit of nihilism. Implanting a profound sense of human fragility into the global consciousness helped give them all a sense of perspective. Nothing can last forever. There's no point to being the best. The only solace we have in the vast and indifferent universe is each other, and isn't it important, then, to make life better for ourselves and everyone around us? This is how we finally reached the stars: together. Upon making contact with other sapient beings, we carried this lesson with us and did our best to befriend them. Astra Planeta operates on the principle that the Great Filter is the shedding of tribalism, and assumes that the human species is smart -and kind- enough to achieve this.

Astra Planeta is existentially optimistic in assuming that life is not rare in the universe at large, and thus there are not only dozens of worlds nearby which harbor biospheres, but there are also several advanced, peaceable civilizations in close proximity -both in space and time. Statistically, the number of civilizations in the setting implies a maddeningly large number of contemporary civilizations present in the galaxy at large, which does not line up with current evidence whatsoever. It breaks from expectation not only with first contact happening at all, not only with first contact going relatively well, but with multiple first contact events all going relatively well. It assumes that mutually intelligible communication is possible for all contact events, and that most contemporary civilizations share our basic morals and aspirations in some sense. All of these elements are, given our current hypotheses on alien life, immensely improbable –but not impossible. Granted, this isn't baseless contrivance purely to make the setting interesting; there is underlying justification for most of the more conspicuous contrivances. For example: taking our planet Earth's biosphere as a point of reference, it seems likely that if complex life exists anywhere in the universe for a long enough span of time, it will evolve some degree of sapience. Odds seem to be very slim that any of these hypothetical sophonts would develop advanced technology, and even less to the point of globalization and multi-planetary society. But the fact remains that they could, and in a universe where life is far more abundant than expected, a small fraction of biospheres generating spacefaring civilizations still makes for quite a few spacefaring civilizations. ASP does not posit that the clockwork of reality has a conscience and is merciful –it is often explicit in stating that the universe simply is what it is. What it does posit is that, however statistically improbable this may seem given our current level of understanding, the cosmos is practically teeming with life. Without this concession to "realism," the premise of the setting falls apart completely.

All three of these assumptions are crucial to the Astra Planeta canon, as their interplay forms the diverse interstellar near-utopia that is the United Spacefaring Sophonts Coalition –which, of course, the setting centers on. As mentioned, ASP does not assume that the forces of nature are kind; the randomly catastrophic nature of the universe is the prime source of narrative conflict here. But Astra Planeta stands as my monument to hope: a world that is better, but still interesting.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk :)

The Lost Starfarers

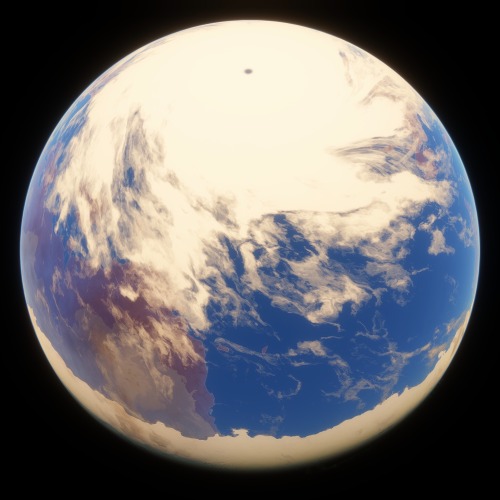

An excerpt from the book The Lost Starfarers by Dr. Erin Burke, published March 2472 CE. Image: the planet Hemera in 2470, seen from high orbit.

Ten thousand years ago, the apocalypse happened.

Not on Earth, of course; we were spared, and our pre-agricultural ancestors never knew the fortune that had shone upon them. But the ruins of nearly a hundred worlds in nearby space tell us everything: ten thousand years ago, the world ended eighty-seven times at once. Far more, in fact, if one counts the tens of thousands of shattered stations and constructs that lay scattered across the expanse of more than a dozen solar systems. Our own system did not fully escape this fate, and indeed the derelict station over Uranus is how we came to realize that, once, long ago, humanity was watched over by beings far more powerful than ourselves.

In our fledgeling centuries of starfaring we would come to learn that these beings called themselves "skgri'i," and came from a world called "o'Kora" -the planet now known to us as Hemera. Over two thousand metric years, they spread across the stars, developing their science and technology to heights we still will not match for another dozen centuries. And yet, somehow, they did not fully shed their primordial divisive nature –much the same nature as the human race– and this was ultimately their undoing.

Our predecessors, our cosmic kin who once flourished across the stars for millennia, were erased from existence in thirteen short years by the most cataclysmic war in known xenoarchaeological history -so absolute in its destruction that it has been simply dubbed "the Apocalypse." We know very little of the conflict itself, or of the terrible weapons with which it was fought, but we can still see plainly the cost that was paid: billions of souls eradicated by the actions of a few; thriving global ecosystems turned to dust in mere seconds; planets left scarred with radioactive craters and unnatural volcanic glass. Most worlds in space are simply dead, inert from their birth... but can you fathom looking upon a world which was killed?

Centuries ago, Earth’s scholars puzzled over the lack of evidence for advanced intelligent life in the universe. After much thought and debate, some proposed an event common to the development of all sapient species called the Great Filter: that which determines whether a civilization will achieve starflight or collapse into oblivion. The ancient Hemerans show us the sobering truth: only cooperation will see us through the Great Filter, because cooperation is the Great Filter. We must take to heart the lesson which those magnificent starfarers did not survive to learn: if we do not forge our path through the stars with goodwill and camaraderie, all that awaits us is the end.

FTL in Astra Planeta

All known interstellar civilizations in the Astra Planeta canon are capable of faster-than-light travel, in some cases (skae and Calypsians) thanks to the teachings of humanity, but mostly because of their own scientific merits. The only known form of macroscopic FTL travel is the warp drive, which has historically been achieved a few hundred years into each civilization's spacefaring age since the physical and engineering challenges that must be overcome to actually make a working prototype are extremely complex.

A warp drive works by bending spacetime in such a way as to simply amplify the vessel's real velocity; it doesn't actually generate any acceleration. An object's real velocity at warp drive activation determines its FTL velocity, but it takes time to accelerate to that real velocity at a safe acceleration (one standard Earth gravity). What results is a tradeoff between the time spent speeding up and slowing down, and the time spent in warp, which varies depending on distance and real velocity.

Finding the optimal interstellar vector utilizes a simple asymptotic formula (created by @catgirlbionics, thanks again!) involving three variables: the distance to the target in lightyears (d), the warp amplification factor (a), and the maximum real-space velocity of the object as a decimal value of the speed of light (v). This function equates to the total flight duration in days (T).

(707.646*v)+((d/(a*v))*365) = T

By plugging in specific values for (d) and (a), and then deriving the function, its positive local minimum will be equivalent to the shortest possible travel time and ideal velocity for the given interstellar vector. For example: a modern Generation VI warp drive has a maximum amplification factor (a) of about 4000, and the distance between Sol and Alpha Centauri (d) is about 4.34 lightyears. Using these values in the formula results in an optimal velocity (v) of about 0.0237c, and a minimum travel time (T) of 33 and a half days!

Warp drives have limited usefulness due to the enormous amount of power they require and the peculiar effects of bending spacetime. Acceleration must be accomplished in real-space or else the exhaust from the engine will reflect off the drive's event horizon and cook the ship, and the same goes for any heat radiated by the vessel. This is why warp drives typically operate in "stuttered" format: an interstellar flight is composed of multiple FTL segments interspersed with periods of real-space STL flight where the ship dumps the heat accumulated by the drive into space via radiator.

Warp drives are not the only method of circumventing the speed of light. Wormholes are also physically possible; however, the largest stable wormholes ever documented are of atomic scale, and anything with rest mass passing through the singularity will cause it to collapse. Wormholes, therefore, are only used to facilitate FTL communication in the form of ansibles, passing extremely narrow laser beams around a network of linked wormholes to achieve near-instantaneous communication.

Because of their nature as loopholes in relativity, both technologies incur some very bizarre effects when it comes to temporal reference frames. Ansible connections where one end is moving at relativistic speed create a combination of wavelength shift and frame dragging that render it impossible to communicate in lockstep; a warpship with a relativistic real-space velocity will result in some time-disparity between passengers and their destination upon arrival. However, it's generally agreed that these complications are a small inconvenience compared to an interstellar society without FTL, where time-slips of decades or more would be a haunting reality.

For All Mankind

Ares 1 \\ Mission Day 128 \\ Surface Mission Day 30 \\ 11/02/2018

Commander Anna Wilson gripped the United Nations flag in her hands and closed her eyes as she unfurled it. The camera Ari held was now rolling, and despite the isolation lending her the confidence to do this, she was still a bit nervous. The light-lag delay of mission control’s inevitable reaction wasn’t helping the anxiety bubbling under her conscious mind. What would they think? What would the world think?

She thought back to training, years ago, when the mission was still a young idea. She had confessed to her crew, in private, her thoughts about the inevitable flag-planting ceremony. To her surprise -and delight- they were in agreement: planting a flag would send the wrong message. It was an archaic practice too laden with negative symbolism, no matter the intentions. So for the next several months, in moments of free time away from the watchful eyes of NASA, they'd planned an alternative. And now, seven light-minutes away from Earth with no one to stop them, they could enact it.

Anna inhaled deeply, faced the camera with the flag, and spoke: “We do not claim this world.” She began rolling the flag back up to stow in her pack. “We will not plant here the flag of any nation or even all nations, because this mission -our presence here today- is much greater than the concept of nations. We came here, to another world, in peace for all mankind. So we cannot plant a flag. It represents arrogance and dominance.” The clock was ticking now. The video stream was hurrying back to Earth, but the whole ceremony would be over before the reply arrived. We’re on our own script now, she thought. Better not mess it up.

As they’d agreed, Oye produced a small aerosol can from his pack -spray paint, specially engineered by a friend to resist the environmental conditions of Mars. Their mark here would endure everything short of a direct meteor strike for millennia. He began to walk toward the rock outcropping nearby, with Ari and Ayami falling in behind him.

Anna brought up the rear, and continued to speak as Ari swiveled the camera back over his shoulder. “Instead, we leave behind only our footprints, which mark our journey…” She paused, and placed a hand on the ancient rock face, making sure Ari was pointing the camera at it. “…and our handprints, showing that we do not seek to claim this world –only to know it.”

Oye gently shook the can and blew the dust from the rock with an airbrush, normally used for geology sampling. Anna blinked a little longer than normal. Here we go.

He aimed the nozzle at her hand and pressed down. The paint sprayed out into the thin air around her suit glove, staining the glove and surrounding rock a deep, cobalt blue. The mission director and tech teams would be pissed, but the crew had taken precautions: covering the tools, wrist camera, and flashlight with tape. When Oye finished moments later, Anna lifted her hand and gazed at the blue stenciled outline on the three-billion-year-old alien sandstone.

As the rest of the crew created their hand stencils, Anna continued. “Maybe in a thousand years, Mars will have its own flag; its own nations. But the marks we leave here today prove to the future that we came not as envoys of nations, but as people, baring our raw humanity for all to see just like our ancestors a hundred thousand years ago. We are here today not only as representatives of our fellow humans, but on behalf of our oldest ancestors, who did not know of nations; they only knew how to be human. These markings are for them as much as they are for us.”

She took a step back as Ari passed her the camera, and aimed it at the four painted hands on the Martian rock. She zoomed in a little to emphasize her closing statement. “Across all of time and space, we are one people, forever.”

“The first rule of starfaring: do not stare into hyperspace. Never, ever, stare deep into hyperspace; not because of what is there -it is not a separate place from the space we know- but because of what it is. Hyperspace is simply normal space in another direction, one you could not think of if you wanted to, and that in itself is the problem. When a ship flies through hyperspace, it moves by vectors that we can only understand through the comfort of abstract math. Watching it happen before your eyes is a sure way to drive yourself mad. Because the second you stop staring at that void, you will know that for a fleeting moment you understood God, and the only way to get that moment back is to confront the void again.”

— Brother Nicodemos of the Order of Saint Mercurion, describing voidthrall

Voidthrall is the insanity which befalls those who have spent too much time directly observing the reality of hyperspace. Within the shifted resonance state of hyperspace the mind can, to some extent, process the nature of fifth-dimensional reality, as the neural connections made to do so utilize the extra dimension. However, upon the return to the fourth-dimensional resonance state, these connections are inaccessible, leaving only the impression of a greater understanding and the burning itch to know something just beyond reach.

Voidthrall is, without exaggeration, eldritch madness: an obsession with the inherently unfathomable. The afflicted are haunted by echoes of things they cannot imagine without the bone-deep humming of a ship's hyperdrive, unable to make use of this knowledge, yet still plagued by memories of a far greater truth. The longer the afflicted have gazed into the abyss, the more desperate they become to regain their comprehension of the incomprehensible.

The madness is, to date, incurable. The only effective treatment able to soothe those who pathologically seek the unknowable truth is further exposure to hyperspace, until the point where the afflicted become unable to neurologically function in normal space.

Rewrote this for WorldEmber '23 and put it up on the WorldAnvil page as its own article. (Yeah, I edited the original post here too.) It might be one of my personal bests, alongside Apotheosis.

Alone Together

Every now and then, someone will ask, "why is it still called first contact?" They think they are clever, apparently, by pointing out that we already know intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, and so it should simply be called 'contact.'

But it is clear that they do not understand the weight these words carry.

Far back in 2145, humankind made first contact on a small, airless, inner moon of Uranus. Except... no one was there to greet us. All we found were the remains. Within a week, our understanding of life in the universe had gone from hopeful optimism to somber concern: had we really been so close to contact, only for our elder and only counterparts to vanish? Research on the ruins revealed that the ancient starfarers had wiped themselves out in a catastrophic civil conflict, and we feared what that meant for us. We resolved, then, that we would do better, not only for ourselves but for the ones who had come before us and lost their way. We had given up one kind of loneliness -that of simple ignorance- for another, far worse kind of loneliness: that of the sole survivor.

Our loneliness was not to last, fortunately. In 2191, the crew of the Arete mission to Proxima Centauri encountered a species of lifeform on the frigid moon Calypso which exhibited unusual intelligence, and in time discovered the great settlements they inhabited. After two years of study, the Arete explorers established rudimentary two-way communication with the Calypsians and grew a conversational relationship with the people of one nearby settlement. Humankind was overjoyed: here, at last, were the interstellar neighbors we had longed for.

But eventually the Arete mission had to return to Earth, and the Calypsians would not achieve interstellar radio transmission for a hundred more years. Even once they were able to commune with us across the great void, we found that our species were too different to have much in common aside from scientific interest. Thus, we were faced once more with a new and uniquely tragic kind of loneliness -almost that of estranged cousins.

In 2220, our prayers seemed to be answered at last by a stray radio signal from Tau Ceti. Though it took time, we were able to decipher its meaning and sent a return message, followed by a probe. The initial course of contact was slow, as is always the case with remote contact from across the emptiness. Over patient years of interaction, we learned how to communicate with the skae, and eventually sent a crewed mission to their homeworld of Ra'na: Andromeda One, the first of many.

We discovered the skae were a younger civilization than us, by several centuries, and so took responsibility for teaching them to be more like us. We taught them the secrets of nature and technology that they had not yet uncovered- of black holes and quarks, of the microchip and the fusion reactor. They accepted our gifts with wonder and gratitude, and in turn taught us their ways of terraformation- new methods to accelerate the healing of our own world and transform others from dead waste to bountiful gardens. Together we founded a coalition, to unite all civilizations seeking starflight under the common purposes of curiosity and betterment. But although this was everything humanity had ever wanted, we still felt the pangs of loneliness: the burden of the elder and mentor.

It was our good fortune, then, that elder civilizations were watching us. Just a decade after founding the USSC, Earth received a radio message from the star Epsilon Indi. It was a direct greeting, excited and hopeful. "We are shyxaure of Delvasi and ziirpu of Virvv. We saw you," they said, "and you have done well. We have ached to reach out for centuries, but worried over what would follow if we did. The alliance you have forged with the people of Tau Ceti is assurance that we are, truly, alike in thought. We are proud to call you neighbors, and hope to soon call you friends."

While we waited for their embassy ship to arrive as promised, humanity reveled in passing a test we had not known was ongoing. We had proven ourselves worthy of contact, worthy of inclusion into the interstellar community... and yet, a new loneliness seeped through the cracks of our joy. We had anguished in isolation for so long, all the while our cosmic seniors watched from not so far away. For hundreds of years, we had not realized there were new friends just beyond the horizon. And so, in secret, we mourned this loneliness: that of what could have been.

In the centuries that have followed we have discovered even more sapient beings around us: the rimor of the Eridani Network, the Xib Zjhar of Xiilu Qam, the pluunima of Niima. We are connected to each other in many ways, but the most important of these is simply that we share the gift of sapience. In this vast and quiet universe, any fellow intelligence is infinitely precious because we are the only ones, as far as we know. Every contact event is first contact, all over again, because every new civilization that we encounter will expand our horizons just enough for us to wonder: "was that last contact? Is there still someone else out there, or is that the end of roll call? Are we alone together, now?"

This, the grandest and most poignant of all mysteries, is why the motto of the Coalition is "solum habemus invicem et stellas" – "we only have each other and the stars."

"We're finally out of the cradle. Of the hundred billion humans who ever lived, we're the first to stand beneath an alien sky."

— CDR Anna Wilson's first words on Mars; Oct. 3, 2018 CE

The Ares program was a crewed spaceflight project led by NASA, in collaboration with other members of the United Nations Aerospace Coalition, that succeeded in its milestone goal of landing humans on the surface of Mars. From its announcement in 2010 it took another eight years of preparation, training, and construction before the first mission was ready to begin.

Ares 1 was launched in mid-2018 and reached the red planet a few months later. At 10:45:33 UTC on October 3rd, 2018, commander Anna Wilson of the United States became the first human being to ever set foot on Mars and the first living thing on the planet in almost four billion years. Ares 1, and the four missions to follow, greatly enriched humanity's understanding of Mars. Ares 5 returned home in early 2028, ending the first crewed Mars exploration phase and opening the door for the next.

The Ares program was the most exciting thing that had ever happened to humankind at the time, and captivated the public imagination for over a decade. Like its predecessors Apollo and Artemis, it is widely recognized across the 30th-century human diaspora as a key reason for humankind's modern status as adept starfarers, best expressed by Commander Wilson in her first words upon touching the Martian surface: "We're finally out of the cradle."

Spy's OCs: Zak Kaiyo

art by my good friend, the wonderful @wildegeist!

Realm: Arcverse Species: Tokaya Homeworld: Terotewaukia (Teroteaumia system) Age: 26 annua (29 Earth years) Gender (human analogue): cismasculine (he/him, xe/xen*) Height: 1.8 m Weight: 72.5 kg Occupation: Captain and pilot of the starship Free Spirit; freelance cargo-hauler; occasional mercenary; jack-of-all-trades [Suggested Listening: Burn Out Brighter by Anberlin]

Zakane "Zak" Kaiyo is the co-owner, captain, and pilot of the heavily-modified light hauler Aum Hara (otherwise known as the "Free Spirit") and the leader of a small band of freelance spacers that make their home aboard the ship. He's just one more spark in the great spiral; one more restless soul trying to make a living doing what he can in a galaxy that's always moving and yet always standing still. From the Tyrian Shallows to the Drift and everywhere in between, Zak and his small but loyal crew of misfits can be found anywhere something interesting is happening.

Zak's talented -albeit reckless- piloting skills earned himself and his copilot Arkto a spot in the Galactic Spacecraft Pilots Association Hall of Fame, having broken the record for the smallest crewed ship by mass to exceed 10 million times the speed of light with a hyperdrive. His performative stuntwork is also renowned, and he frequently attends the annual Galactic Pilot Convention.

Most of the "swashbuckling freelance ace pilot" tropes apply to this space hobo, whose personal creed is "do good recklessly." His confidence, determination, and cheerful sarcasm make for an extremely charismatic, if reckless, leader. He's very mischievous and likes to get into trouble, but can be relied on to get out of it as quickly as he gets into it… most of the time. Zak acts fearless but, go figure, this man has Attachment Issues. He hates the idea of getting tied down to one place or thing, yet at the same time he is fiercely protective of his crew. (Shhh. Nobody tell him.)

Zak's homeworld is a backwater: connected to the galaxy and participant in its affairs, but hardly anyone there actually got out beyond the system. He was constantly told that he ought to be happy on Terotewaukia, fixing up interplanetary haulers and maybe going to the outer moons of the system once in a while. He and his two best friends always wanted more. The three of them had plans to quietly fix up one of the written-off hauler derelicts on company time and get the hell out, making their way around the wild starry yonder to see what could be seen.

And then one of them decided they wanted to stay and settle down.

That was the last straw for Zak. As soon as the opportunity arose, he and Arkto (his other bff) took off in their souped-up light hauler and never looked back. But once they were out there... Zak came to realize that the galaxy isn't a really adventurous place.

See, Arcverse is a universe that everyone thinks has been more or less figured out. Galactic civilization has been around for something like a million years or so, and the Arcadian Order have been sort of running the Galactic Assembly for about that long (mostly because they got off their planet first and they do a pretty decent job of wrangling the rowdier civilizations with diplomacy). The entire galaxy is, broadly speaking, at peace. The clash of titans already happened; the fate-of-the-galaxy-level stakes were sorted out thousands of generations ago. All the major starfaring powers, while independent in principle, are constrained by the bureaucracy of the Galactic Assembly. There's mild internal turmoil —and there's always an underbelly— but it's still quite tame. There's a whole galaxy out there with lots to see but nothing to really strive for in it.

Zak Kaiyo is someone who desperately, fundamentally, needs to strive. He wants to live fast and die young in a galaxy where everyone lives at a reasonable pace and dies basically never. He exists to challenge the stagnancy of a world that's as close to utopia as it can reasonably be. Zak wants so badly to save the galaxy, but he lives in a galaxy that doesn't need saving. And that's tearing him to pieces.

Character Introduction - Meridian Shardd

If you like this, please REBLOG! 💕

☆・・Aesthetic/Moodboard ・・☆

════════════════════════════════════════════

☆ ・・About/General Info ・・☆

A cyborg/robot created for entertainment, Meridian long since yearned to know what it truly meant to live and be human. Finding an unexpected opportunity to rebel against their creator, Meridian broke free of the coding they'd been trapped to since the moment of their creation and escaped from the Khosmonian Galaxies in search of a future where they could truly be free. Naive, innocent, and painfully unaware of how real humanoid interactions actually work, especially in such a conflicted set of galaxies, Meridian wandered completely lost for a while, trying to not fall back into the hands of their inventor - who would for sure reprogram them and stop them from achieving their dream of experiencing real life - until they met a strange, but kind, group of thieves and space adventurers who became their friends and the closest thing to a family they ever had. Perhaps being human won't be such an unattainable dream as they thought.

════════════════════════════════════════════

☆・・More Info ・・☆

Pronouns - They/Them (main pronouns), He/Him (occasionally)

Age - They have been alive for less than a decade but have the appearance/biology, mental age, and personality of a young adult in their early 20s.

Current Role - Part of the main cast

Appearance - Meridian has medium to long hair, synthetic, which they can change/choose the color of at will (their favorite hair colors are bright neon pink, cyan, or deep gold). Their skin is pale and perfectly smooth, akin to a porcelain doll, and some of their robotic joints are visible, with golden wiring/servos within (like an automaton, but high tech and sentient). Their eyes can also change color at will, and they usually match their eye color to their hair color of the day because they like symmetry. Meridian is considerably tall, standing at 6,2ft or around 187cm, and because they tend to wear heels (they like it) with wheels, they're usually even taller. Their features are rather androgynous, though their design leans more towards a somewhat masculine appearance.

Personality Types -

✶ Enneagram: 7w6

✶ MBTI: ENFP

Occupation: Formerly - Servant/Entertainer (dancer, singer); Currently - Adventurer, Rebel

Species & Place of Birth: Cyborg/Sentient Robot, Khosmo

Sexuality: Nonbinary. Otherwise, probably still haven't figured out their exact sexuality/romantic tendencies yet though.

════════════════════════════════════════════

☆・・Extras・・☆

✶ Character Playlist

Playlist Sneak Peek:

Summer Sunshine - Sweetersongs

I'm Just a Kid - Simple Plan

Are You Satisfied? - Marina And The Diamonds

Not Your Barbie Girl - Ava Max

I'm Good (Blue) - David Guetta, Bebe Rhexa

Bubblegum Bitch - Marina And The Diamonds

And more!

・・・

✶ Tags:

#wip supernova initiative #oc: meridian shardd

・・・

Supernova Initiative Taglist (-/+): @ray-writes-n-shit, @sarandipitywrites, @lassiesandiego, @smol-feralgremlin, @kaylinalexanderbooks,

@saturnine-saturneight @diabolical-blue @oh-no-another-idea

@cakeinthevoid, @clairelsonao3, @sleepy-night-child

@thepeculiarbird

@the-golden-comet, @urnumber1star, @ominous-feychild, @anyablackwood, @amaiguri, @lyutenw @finickyfelix

@elshells, @thecomfywriter

Let me know if you'd like to be added!

Source for moodboard pictures & music playlist: Pinterest & Spotify respectively