Scifi Writing - Tumblr Posts - Page 2

Awakening

Voices.

That was the first thing I was aware of, breaking through the tranquil oblivion like a stone cast into a still pool. Someone was speaking, though I couldn't make out what was being said. It sounded distant, as if a league of water separated us. Grasping weakly at consciousness, I tried to call out, to stir...

And the second thing I became aware of was the pain.

I became reacquainted with my body as a dull ache spread through it, starting with my head and making its way down my core and out to my limbs. The ache gradually intensified as the moments dripped by, as did the voices. Though still muffled, as my sentience returned to me I realized I could neither recognize nor understand them. Still unable to move, I found the only muscles that would respond to me were my eyelids. I opened them, eager to test another sense.

I saw nothing at all, just the same oppressive, featureless darkness. The only thing that changed was some sort of cold fluid now pressing against my exposed corneas. I panicked for a fraction of a second, suddenly afraid of drowning, before realizing I was still breathing. As tactile sense surfaced above the omnipresent ache, I became aware of a breathing mask over my face, as well as IV feeds in my arms and electrodes all over my body. What was all that about…?

It occurred to me then that I did not know where I was. The first coherent internal dialog I produced was a simple ‘oh no,’ as my heart began to pick up its pace. The last thing I remembered… I was on a vast ship, bound for a distant star, never to return. Had we arrived at long last?

A loud, beeping alarm startled me. Despite the pain, confusion, and weakness suffusing every fiber of my being, at last I began to stir. So too did my surroundings: there was a quiet rumble and an accompanying hiss as the frigid fluid started to drain. The voices changed cadence, evidently surprised, and got louder- no, closer.

Though the light was dim, it nearly blinded me as the cover of my stasis chamber was lifted open. I squinted at the shapes attached to the voices; they were blurry and indistinct. One of them leaned closer, and I was able to resolve some features. Long, white hair, elegant feminine facial structure, piercing golden eyes. A pair of shapes loomed just behind them, large and white and triangular. Feathered. Were those… wings?

The person said something- a question I couldn't understand. They gently removed the breathing mask. I coughed at the first taste of stale, cold air, and the pain flared in my chest, threatening to shake my grasp on the waking world. The stranger touched my face with delicate grace, concern apparent on their own. I was struck by a thought.

“Are… you… an angel?” I managed to gasp, weakly.

My savior frowned, and said something else that was lost on me. The other voice, from somewhere outside my field of vision, gave a reply that seemed to disappoint them. I understood only one word, a name I vaguely recalled from somewhere in ancient mythology: “Mnemosyne.” The winged being nodded, and placed the mask back over my mouth and nose. Before I could protest, they placed some sort of device against my forehead, and I sunk back into dreamless nothing.

When I awoke again, a different voice greeted me -one I could understand, this time.

“Hello, friend,” it said. It was soft, pleasant… welcoming.

I opened my eyes, but the light was too bright, and I shut them quickly.

“Please, take your time adjusting to the burden of consciousness; you have been in stasis for a very long time.”

Stasis. Yes. Now that I was awake, we must have reached our destination. I noted, with relief, that the all-consuming ache was no longer all-consuming. The air was warm, and fresh. I opened my eyes very slightly, letting them acclimate to the revival room.

“That’s it, ease into the heat and light,” the voice encouraged me. “There we go.”

After several minutes, I felt able to look around. I sat up, slowly, carefully, and looked for the source of the voice. To my great surprise, I was not in the revival room… or at least, not one that I recognized. The room was small, clean, and colored in gentle pastels. I was further shocked to discover that the voice was that of a friendly-looking robot, humanoid in shape, holding some sort of electronic tablet.

“Hello!” they said, and smiled. Their smile, amazingly, was somehow reassuring. “I am Mnemosyne, your post-stasis bedside attendant.”

“H-hello…?” I managed. “What… what is… where am I?”

“Ah, let me get you up to speed. Welcome to the fifty-third century of what you most likely know as the Common Era.”

I blinked, failing to grasp the meaning of the sentence. “The what?”

Mnemosyne continued. “Oh yes, it has been some time indeed, but please save all your questions for the end of this orientation. According to your chart, you have missed…” They glanced at the information on the pad. “...approximately three thousand and twenty-four years of intervening time.” They paused, and a look of concern crossed their artificial face.

“Oh dear. You should probably lie back down for this.”

Alone Together

Every now and then, someone will ask, "why is it still called first contact?" They think they are clever, apparently, by pointing out that we already know intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, and so it should simply be called 'contact.'

But it is clear that they do not understand the weight these words carry.

Far back in 2145, humankind made first contact on a small, airless, inner moon of Uranus. Except... no one was there to greet us. All we found were the remains. Within a week, our understanding of life in the universe had gone from hopeful optimism to somber concern: had we really been so close to contact, only for our elder and only counterparts to vanish? Research on the ruins revealed that the ancient starfarers had wiped themselves out in a catastrophic civil conflict, and we feared what that meant for us. We resolved, then, that we would do better, not only for ourselves but for the ones who had come before us and lost their way. We had given up one kind of loneliness -that of simple ignorance- for another, far worse kind of loneliness: that of the sole survivor.

Our loneliness was not to last, fortunately. In 2191, the crew of the Arete mission to Proxima Centauri encountered a species of lifeform on the frigid moon Calypso which exhibited unusual intelligence, and in time discovered the great settlements they inhabited. After two years of study, the Arete explorers established rudimentary two-way communication with the Calypsians and grew a conversational relationship with the people of one nearby settlement. Humankind was overjoyed: here, at last, were the interstellar neighbors we had longed for.

But eventually the Arete mission had to return to Earth, and the Calypsians would not achieve interstellar radio transmission for a hundred more years. Even once they were able to commune with us across the great void, we found that our species were too different to have much in common aside from scientific interest. Thus, we were faced once more with a new and uniquely tragic kind of loneliness -almost that of estranged cousins.

In 2220, our prayers seemed to be answered at last by a stray radio signal from Tau Ceti. Though it took time, we were able to decipher its meaning and sent a return message, followed by a probe. The initial course of contact was slow, as is always the case with remote contact from across the emptiness. Over patient years of interaction, we learned how to communicate with the skae, and eventually sent a crewed mission to their homeworld of Ra'na: Andromeda One, the first of many.

We discovered the skae were a younger civilization than us, by several centuries, and so took responsibility for teaching them to be more like us. We taught them the secrets of nature and technology that they had not yet uncovered- of black holes and quarks, of the microchip and the fusion reactor. They accepted our gifts with wonder and gratitude, and in turn taught us their ways of terraformation- new methods to accelerate the healing of our own world and transform others from dead waste to bountiful gardens. Together we founded a coalition, to unite all civilizations seeking starflight under the common purposes of curiosity and betterment. But although this was everything humanity had ever wanted, we still felt the pangs of loneliness: the burden of the elder and mentor.

It was our good fortune, then, that elder civilizations were watching us. Just a decade after founding the USSC, Earth received a radio message from the star Epsilon Indi. It was a direct greeting, excited and hopeful. "We are shyxaure of Delvasi and ziirpu of Virvv. We saw you," they said, "and you have done well. We have ached to reach out for centuries, but worried over what would follow if we did. The alliance you have forged with the people of Tau Ceti is assurance that we are, truly, alike in thought. We are proud to call you neighbors, and hope to soon call you friends."

While we waited for their embassy ship to arrive as promised, humanity reveled in passing a test we had not known was ongoing. We had proven ourselves worthy of contact, worthy of inclusion into the interstellar community... and yet, a new loneliness seeped through the cracks of our joy. We had anguished in isolation for so long, all the while our cosmic seniors watched from not so far away. For hundreds of years, we had not realized there were new friends just beyond the horizon. And so, in secret, we mourned this loneliness: that of what could have been.

In the centuries that have followed we have discovered even more sapient beings around us: the rimor of the Eridani Network, the Xib Zjhar of Xiilu Qam, the pluunima of Niima. We are connected to each other in many ways, but the most important of these is simply that we share the gift of sapience. In this vast and quiet universe, any fellow intelligence is infinitely precious because we are the only ones, as far as we know. Every contact event is first contact, all over again, because every new civilization that we encounter will expand our horizons just enough for us to wonder: "was that last contact? Is there still someone else out there, or is that the end of roll call? Are we alone together, now?"

This, the grandest and most poignant of all mysteries, is why the motto of the Coalition is "solum habemus invicem et stellas" – "we only have each other and the stars."

I'm starting to come back around to Astra Planeta in a really substantial way, and if you don't mind I'm gonna think out loud here for a little.

Astra Planeta is categorically hard science fiction, in that it adheres to the definition of the genre: the scientific and technological elements presented in the world's canon are within the realm of what we consider possible with our current collective knowledge of science and technology. However, ASP breaks the mold of hard science fiction by being optimistic in three key ways: technological, social, and existential.

Astra Planeta is technologically optimistic in assuming that any engineering problem standing between us and efficient interstellar travel can be solved. According to the canon timeline, fusion power is relatively commonplace by the mid-21st century, and by the start of the 22nd century humanity have developed a proper torchship. Human health issues stemming from long-term space travel are easily resolved with high-power magnetic shielding and centripetal pseudo-gravity, plus a touch of good ol' genetic therapy to keep the body strong and healthy. Wormhole technology is developed for instantaneous communication by the 22nd century, and by the end of the 23rd century humans have begun to unlock faster-than-light travel by engineering our first warp drive. In the few centuries between the first spaceflight and the first extrasolar mission, humans figure out (non-cryogenic) stasis, perfect closed-system environment maintenance, and build AI with thought patterns so similar to people they might as well have souls. We have our cake and eat it too. All of this is within the scope of "scientifically possible," though certain parts are hotly debated in academic circle. But the rapidity with which we achieve these milestones is shamelessly optimistic. It has to be, or else the premise of the setting falls apart.

Astra Planeta is socially optimistic in assuming that humanity, as a global entity, can overcome -or at least overlook- the cultural divisions which set people apart and cooperate as a singular civilization. I've talked about this extensively elsewhere, but one of the keystones of the project is the thorough demilitarization of planet Earth and all her nations. By the end of the 21st century, "war" is a word that has passed out of the news cycle and into history books. It took some doing, sure, but in this reality humankind was faced with the imminent degradation of their home planet and collectively decided that there were bigger fish to fry than each other. Complex issues left unresolved for generations were gradually untangled and sorted out, with a lot of patience and a bit of nihilism. Implanting a profound sense of human fragility into the global consciousness helped give them all a sense of perspective. Nothing can last forever. There's no point to being the best. The only solace we have in the vast and indifferent universe is each other, and isn't it important, then, to make life better for ourselves and everyone around us? This is how we finally reached the stars: together. Upon making contact with other sapient beings, we carried this lesson with us and did our best to befriend them. Astra Planeta operates on the principle that the Great Filter is the shedding of tribalism, and assumes that the human species is smart -and kind- enough to achieve this.

Astra Planeta is existentially optimistic in assuming that life is not rare in the universe at large, and thus there are not only dozens of worlds nearby which harbor biospheres, but there are also several advanced, peaceable civilizations in close proximity -both in space and time. Statistically, the number of civilizations in the setting implies a maddeningly large number of contemporary civilizations present in the galaxy at large, which does not line up with current evidence whatsoever. It breaks from expectation not only with first contact happening at all, not only with first contact going relatively well, but with multiple first contact events all going relatively well. It assumes that mutually intelligible communication is possible for all contact events, and that most contemporary civilizations share our basic morals and aspirations in some sense. All of these elements are, given our current hypotheses on alien life, immensely improbable –but not impossible. Granted, this isn't baseless contrivance purely to make the setting interesting; there is underlying justification for most of the more conspicuous contrivances. For example: taking our planet Earth's biosphere as a point of reference, it seems likely that if complex life exists anywhere in the universe for a long enough span of time, it will evolve some degree of sapience. Odds seem to be very slim that any of these hypothetical sophonts would develop advanced technology, and even less to the point of globalization and multi-planetary society. But the fact remains that they could, and in a universe where life is far more abundant than expected, a small fraction of biospheres generating spacefaring civilizations still makes for quite a few spacefaring civilizations. ASP does not posit that the clockwork of reality has a conscience and is merciful –it is often explicit in stating that the universe simply is what it is. What it does posit is that, however statistically improbable this may seem given our current level of understanding, the cosmos is practically teeming with life. Without this concession to "realism," the premise of the setting falls apart completely.

All three of these assumptions are crucial to the Astra Planeta canon, as their interplay forms the diverse interstellar near-utopia that is the United Spacefaring Sophonts Coalition –which, of course, the setting centers on. As mentioned, ASP does not assume that the forces of nature are kind; the randomly catastrophic nature of the universe is the prime source of narrative conflict here. But Astra Planeta stands as my monument to hope: a world that is better, but still interesting.

Thank you for coming to my TED Talk :)

The Lost Starfarers

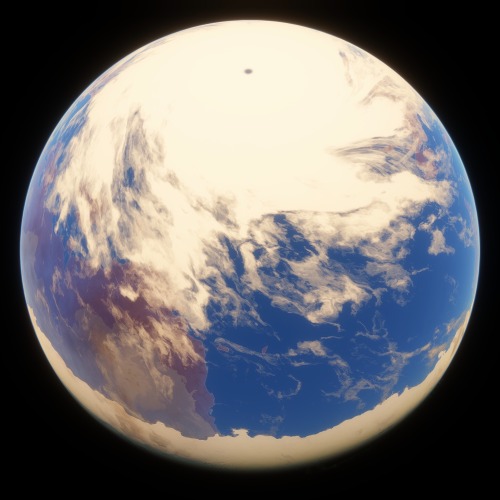

An excerpt from the book The Lost Starfarers by Dr. Erin Burke, published March 2472 CE. Image: the planet Hemera in 2470, seen from high orbit.

Ten thousand years ago, the apocalypse happened.

Not on Earth, of course; we were spared, and our pre-agricultural ancestors never knew the fortune that had shone upon them. But the ruins of nearly a hundred worlds in nearby space tell us everything: ten thousand years ago, the world ended eighty-seven times at once. Far more, in fact, if one counts the tens of thousands of shattered stations and constructs that lay scattered across the expanse of more than a dozen solar systems. Our own system did not fully escape this fate, and indeed the derelict station over Uranus is how we came to realize that, once, long ago, humanity was watched over by beings far more powerful than ourselves.

In our fledgeling centuries of starfaring we would come to learn that these beings called themselves "skgri'i," and came from a world called "o'Kora" -the planet now known to us as Hemera. Over two thousand metric years, they spread across the stars, developing their science and technology to heights we still will not match for another dozen centuries. And yet, somehow, they did not fully shed their primordial divisive nature –much the same nature as the human race– and this was ultimately their undoing.

Our predecessors, our cosmic kin who once flourished across the stars for millennia, were erased from existence in thirteen short years by the most cataclysmic war in known xenoarchaeological history -so absolute in its destruction that it has been simply dubbed "the Apocalypse." We know very little of the conflict itself, or of the terrible weapons with which it was fought, but we can still see plainly the cost that was paid: billions of souls eradicated by the actions of a few; thriving global ecosystems turned to dust in mere seconds; planets left scarred with radioactive craters and unnatural volcanic glass. Most worlds in space are simply dead, inert from their birth... but can you fathom looking upon a world which was killed?

Centuries ago, Earth’s scholars puzzled over the lack of evidence for advanced intelligent life in the universe. After much thought and debate, some proposed an event common to the development of all sapient species called the Great Filter: that which determines whether a civilization will achieve starflight or collapse into oblivion. The ancient Hemerans show us the sobering truth: only cooperation will see us through the Great Filter, because cooperation is the Great Filter. We must take to heart the lesson which those magnificent starfarers did not survive to learn: if we do not forge our path through the stars with goodwill and camaraderie, all that awaits us is the end.

FTL in Astra Planeta

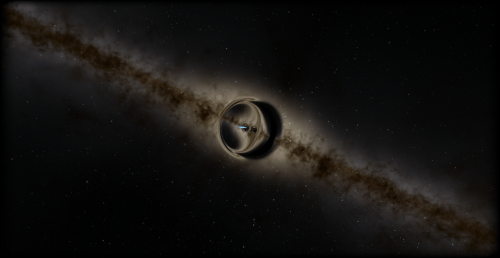

All known interstellar civilizations in the Astra Planeta canon are capable of faster-than-light travel, in some cases (skae and Calypsians) thanks to the teachings of humanity, but mostly because of their own scientific merits. The only known form of macroscopic FTL travel is the warp drive, which has historically been achieved a few hundred years into each civilization's spacefaring age since the physical and engineering challenges that must be overcome to actually make a working prototype are extremely complex.

A warp drive works by bending spacetime in such a way as to simply amplify the vessel's real velocity; it doesn't actually generate any acceleration. An object's real velocity at warp drive activation determines its FTL velocity, but it takes time to accelerate to that real velocity at a safe acceleration (one standard Earth gravity). What results is a tradeoff between the time spent speeding up and slowing down, and the time spent in warp, which varies depending on distance and real velocity.

Finding the optimal interstellar vector utilizes a simple asymptotic formula (created by @catgirlbionics, thanks again!) involving three variables: the distance to the target in lightyears (d), the warp amplification factor (a), and the maximum real-space velocity of the object as a decimal value of the speed of light (v). This function equates to the total flight duration in days (T).

(707.646*v)+((d/(a*v))*365) = T

By plugging in specific values for (d) and (a), and then deriving the function, its positive local minimum will be equivalent to the shortest possible travel time and ideal velocity for the given interstellar vector. For example: a modern Generation VI warp drive has a maximum amplification factor (a) of about 4000, and the distance between Sol and Alpha Centauri (d) is about 4.34 lightyears. Using these values in the formula results in an optimal velocity (v) of about 0.0237c, and a minimum travel time (T) of 33 and a half days!

Warp drives have limited usefulness due to the enormous amount of power they require and the peculiar effects of bending spacetime. Acceleration must be accomplished in real-space or else the exhaust from the engine will reflect off the drive's event horizon and cook the ship, and the same goes for any heat radiated by the vessel. This is why warp drives typically operate in "stuttered" format: an interstellar flight is composed of multiple FTL segments interspersed with periods of real-space STL flight where the ship dumps the heat accumulated by the drive into space via radiator.

Warp drives are not the only method of circumventing the speed of light. Wormholes are also physically possible; however, the largest stable wormholes ever documented are of atomic scale, and anything with rest mass passing through the singularity will cause it to collapse. Wormholes, therefore, are only used to facilitate FTL communication in the form of ansibles, passing extremely narrow laser beams around a network of linked wormholes to achieve near-instantaneous communication.

Because of their nature as loopholes in relativity, both technologies incur some very bizarre effects when it comes to temporal reference frames. Ansible connections where one end is moving at relativistic speed create a combination of wavelength shift and frame dragging that render it impossible to communicate in lockstep; a warpship with a relativistic real-space velocity will result in some time-disparity between passengers and their destination upon arrival. However, it's generally agreed that these complications are a small inconvenience compared to an interstellar society without FTL, where time-slips of decades or more would be a haunting reality.

The United Nations of Humanity is the international governing body of almost all Earth-descended polities and territories in known space. Founded in 2210 CE after the independence movements of Mars and the Belt necessitated a reorganization of the original UN, the UNH of the 30th century is composed of hundreds of member star systems across a sphere of influence nearly twenty parsecs in diameter. It is the largest member of the United Spacefaring Sophonts Coalition and one of the two founding members (alongside the Ra’na InterGlobal Council). The UNH has no primary seat, as all business is conducted through ansible teleconference: a vastly simpler way to organize representatives across sixty-five thousand cubic lightyears of space. Members of the UNH include the United Sol System, Centauri Republic, New Nations of Helios, and Dogstar Alliance, to name a few.

The symbology of the UNH emblem is simple. The asymmetrical five digits of the human hand provide a clear distinction from the other species of the cosmos; we are the only species with hands like ours. Beyond that, the hand represents something much deeper. Handprints are ubiquitous in prehistoric cave art found all over the human homeworld, Earth, and have withstood the test of time. Even today, leaving an impression of one's hand in media echoes the purpose of the ancient hands: it is a testament to our existence, a call into the future that in this place and time, a human person was alive and awake. A footprint may show that we have stood in a spot, but a handprint shows we have lived there.

For All Mankind

Ares 1 \\ Mission Day 128 \\ Surface Mission Day 30 \\ 11/02/2018

Commander Anna Wilson gripped the United Nations flag in her hands and closed her eyes as she unfurled it. The camera Ari held was now rolling, and despite the isolation lending her the confidence to do this, she was still a bit nervous. The light-lag delay of mission control’s inevitable reaction wasn’t helping the anxiety bubbling under her conscious mind. What would they think? What would the world think?

She thought back to training, years ago, when the mission was still a young idea. She had confessed to her crew, in private, her thoughts about the inevitable flag-planting ceremony. To her surprise -and delight- they were in agreement: planting a flag would send the wrong message. It was an archaic practice too laden with negative symbolism, no matter the intentions. So for the next several months, in moments of free time away from the watchful eyes of NASA, they'd planned an alternative. And now, seven light-minutes away from Earth with no one to stop them, they could enact it.

Anna inhaled deeply, faced the camera with the flag, and spoke: “We do not claim this world.” She began rolling the flag back up to stow in her pack. “We will not plant here the flag of any nation or even all nations, because this mission -our presence here today- is much greater than the concept of nations. We came here, to another world, in peace for all mankind. So we cannot plant a flag. It represents arrogance and dominance.” The clock was ticking now. The video stream was hurrying back to Earth, but the whole ceremony would be over before the reply arrived. We’re on our own script now, she thought. Better not mess it up.

As they’d agreed, Oye produced a small aerosol can from his pack -spray paint, specially engineered by a friend to resist the environmental conditions of Mars. Their mark here would endure everything short of a direct meteor strike for millennia. He began to walk toward the rock outcropping nearby, with Ari and Ayami falling in behind him.

Anna brought up the rear, and continued to speak as Ari swiveled the camera back over his shoulder. “Instead, we leave behind only our footprints, which mark our journey…” She paused, and placed a hand on the ancient rock face, making sure Ari was pointing the camera at it. “…and our handprints, showing that we do not seek to claim this world –only to know it.”

Oye gently shook the can and blew the dust from the rock with an airbrush, normally used for geology sampling. Anna blinked a little longer than normal. Here we go.

He aimed the nozzle at her hand and pressed down. The paint sprayed out into the thin air around her suit glove, staining the glove and surrounding rock a deep, cobalt blue. The mission director and tech teams would be pissed, but the crew had taken precautions: covering the tools, wrist camera, and flashlight with tape. When Oye finished moments later, Anna lifted her hand and gazed at the blue stenciled outline on the three-billion-year-old alien sandstone.

As the rest of the crew created their hand stencils, Anna continued. “Maybe in a thousand years, Mars will have its own flag; its own nations. But the marks we leave here today prove to the future that we came not as envoys of nations, but as people, baring our raw humanity for all to see just like our ancestors a hundred thousand years ago. We are here today not only as representatives of our fellow humans, but on behalf of our oldest ancestors, who did not know of nations; they only knew how to be human. These markings are for them as much as they are for us.”

She took a step back as Ari passed her the camera, and aimed it at the four painted hands on the Martian rock. She zoomed in a little to emphasize her closing statement. “Across all of time and space, we are one people, forever.”

“The first rule of starfaring: do not stare into hyperspace. Never, ever, stare deep into hyperspace; not because of what is there -it is not a separate place from the space we know- but because of what it is. Hyperspace is simply normal space in another direction, one you could not think of if you wanted to, and that in itself is the problem. When a ship flies through hyperspace, it moves by vectors that we can only understand through the comfort of abstract math. Watching it happen before your eyes is a sure way to drive yourself mad. Because the second you stop staring at that void, you will know that for a fleeting moment you understood God, and the only way to get that moment back is to confront the void again.”

— Brother Nicodemos of the Order of Saint Mercurion, describing voidthrall

Voidthrall is the insanity which befalls those who have spent too much time directly observing the reality of hyperspace. Within the shifted resonance state of hyperspace the mind can, to some extent, process the nature of fifth-dimensional reality, as the neural connections made to do so utilize the extra dimension. However, upon the return to the fourth-dimensional resonance state, these connections are inaccessible, leaving only the impression of a greater understanding and the burning itch to know something just beyond reach.

Voidthrall is, without exaggeration, eldritch madness: an obsession with the inherently unfathomable. The afflicted are haunted by echoes of things they cannot imagine without the bone-deep humming of a ship's hyperdrive, unable to make use of this knowledge, yet still plagued by memories of a far greater truth. The longer the afflicted have gazed into the abyss, the more desperate they become to regain their comprehension of the incomprehensible.

The madness is, to date, incurable. The only effective treatment able to soothe those who pathologically seek the unknowable truth is further exposure to hyperspace, until the point where the afflicted become unable to neurologically function in normal space.

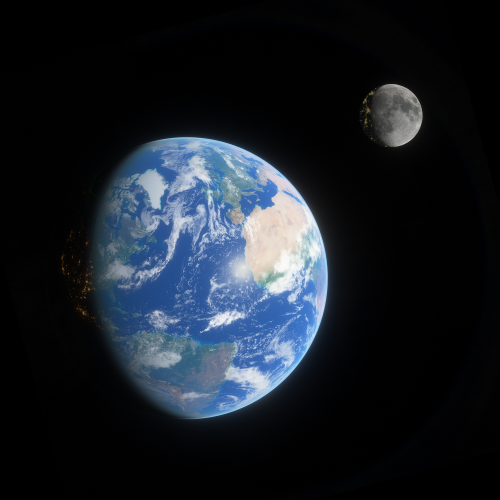

The planet Earth is the third planet in the Sol system, a vibrant terran world with a diverse biosphere recovering from a near-miss ecological collapse. It has six major landmasses surrounded by vast oceans of liquid water, and its atmosphere is a comfortable nitrogen-oxygen blend at a pressure that is dense enough to protect but not enough to crush. It also has one relatively large, airless, rocky moon, called Luna (or simply "the Moon.")

Earth is also home to an indigenous sophont species: humans, one of the founding members of the Coalition of Spacefaring Civilizations. Because of its deep pre-spaceflight cultural history, it is one of a minority of worlds divided into nations, hence its primary governing body being the United Nations of Earth -the ancestor to most of humankind's modern administrative structure. Being Earth's only natural moon, Luna was the site of humans' first forays into extraterrestrial exploration, and today is an industrial powerhouse under the flag of the UN Autonomous Territory of Luna. The Earth-Moon Union (EMU, for short; top flag) is composed of the United Nations of Earth (bottom left flag) and the Autonomous Territory of Luna (bottom right flag), with its primary seat being Midway Station located at the L-1 gravitational stability keyhole between Earth and Luna.

As the birthplace of the human species, the Earth is the most populous and powerful asteropolitical entity in the Sol system, and quite possibly in the entire United Nations of Humanity. Earth itself has a population of just over 8 billion, which has stayed relatively stable since the 21st century. Together with the Moon’s 240 million inhabitants, the total population of the EMU is about 8.4 billion, almost four times that of the next largest entity in the system (Mars).

While Luna’s primary industry in the modern day is mining, Earth’s rich cultural and biological history makes it a tourist destination renowned across known space, though it has stringent biosecurity. For many, it is even a spiritual experience, some going so far as to make it their life’s goal to retire on Earth and connect with the home of their ancestors. Centuries of ecological engineering and conservation have managed to avert the effects of early human industry, restoring the world to a natural balance and even reviving many species driven extinct by human error. Today, one can watch herds of mammoth roam the Siberian tundra, visit dodo birds on Mauritius, or experience the return of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef. 30th century Earth is a good place to be, and humanity is collectively proud of their home: the cradle of the Diaspora.

hey look, more art! been a hot minute. photobash of a future Earth and its well-settled Moon, plus their flags, created for my hard science fiction setting Astra Planeta. done using assets from Space Engine.

October 4, 2181: The UNSS Skyward Spirit ignites its massively powerful fusion drive in cislunar space, beginning its 24-year round trip to Proxima Centauri. Visible on the Moon are the cities of Byrd, Guǎnghángōng, Apollo City, Tsiolkovskiy, Tycho, and Shackleton, as well as many smaller settlements, all connected by the lunar rail system. Off the sunward limb of the Moon one can also spot the city-station Tsukuyomi in low orbit, with half a dozen vessels in its vicinity. Taken by an unknown photographer at dawn on the west bank of Lake Tanganyika (DRC), using a telescopic lens.

a rare Spy Art appears! photobash of the moment humankind started their very first journey to another sun in my hard science fiction setting Astra Planeta. edited in Paint.NET using a screenshot from Space Engine.

Rewrote this for WorldEmber '23 and put it up on the WorldAnvil page as its own article. (Yeah, I edited the original post here too.) It might be one of my personal bests, alongside Apotheosis.

Alone Together

Every now and then, someone will ask, "why is it still called first contact?" They think they are clever, apparently, by pointing out that we already know intelligent life exists elsewhere in the universe, and so it should simply be called 'contact.'

But it is clear that they do not understand the weight these words carry.

Far back in 2145, humankind made first contact on a small, airless, inner moon of Uranus. Except... no one was there to greet us. All we found were the remains. Within a week, our understanding of life in the universe had gone from hopeful optimism to somber concern: had we really been so close to contact, only for our elder and only counterparts to vanish? Research on the ruins revealed that the ancient starfarers had wiped themselves out in a catastrophic civil conflict, and we feared what that meant for us. We resolved, then, that we would do better, not only for ourselves but for the ones who had come before us and lost their way. We had given up one kind of loneliness -that of simple ignorance- for another, far worse kind of loneliness: that of the sole survivor.

Our loneliness was not to last, fortunately. In 2191, the crew of the Arete mission to Proxima Centauri encountered a species of lifeform on the frigid moon Calypso which exhibited unusual intelligence, and in time discovered the great settlements they inhabited. After two years of study, the Arete explorers established rudimentary two-way communication with the Calypsians and grew a conversational relationship with the people of one nearby settlement. Humankind was overjoyed: here, at last, were the interstellar neighbors we had longed for.

But eventually the Arete mission had to return to Earth, and the Calypsians would not achieve interstellar radio transmission for a hundred more years. Even once they were able to commune with us across the great void, we found that our species were too different to have much in common aside from scientific interest. Thus, we were faced once more with a new and uniquely tragic kind of loneliness -almost that of estranged cousins.

In 2220, our prayers seemed to be answered at last by a stray radio signal from Tau Ceti. Though it took time, we were able to decipher its meaning and sent a return message, followed by a probe. The initial course of contact was slow, as is always the case with remote contact from across the emptiness. Over patient years of interaction, we learned how to communicate with the skae, and eventually sent a crewed mission to their homeworld of Ra'na: Andromeda One, the first of many.

We discovered the skae were a younger civilization than us, by several centuries, and so took responsibility for teaching them to be more like us. We taught them the secrets of nature and technology that they had not yet uncovered- of black holes and quarks, of the microchip and the fusion reactor. They accepted our gifts with wonder and gratitude, and in turn taught us their ways of terraformation- new methods to accelerate the healing of our own world and transform others from dead waste to bountiful gardens. Together we founded a coalition, to unite all civilizations seeking starflight under the common purposes of curiosity and betterment. But although this was everything humanity had ever wanted, we still felt the pangs of loneliness: the burden of the elder and mentor.

It was our good fortune, then, that elder civilizations were watching us. Just a decade after founding the USSC, Earth received a radio message from the star Epsilon Indi. It was a direct greeting, excited and hopeful. "We are shyxaure of Delvasi and ziirpu of Virvv. We saw you," they said, "and you have done well. We have ached to reach out for centuries, but worried over what would follow if we did. The alliance you have forged with the people of Tau Ceti is assurance that we are, truly, alike in thought. We are proud to call you neighbors, and hope to soon call you friends."

While we waited for their embassy ship to arrive as promised, humanity reveled in passing a test we had not known was ongoing. We had proven ourselves worthy of contact, worthy of inclusion into the interstellar community... and yet, a new loneliness seeped through the cracks of our joy. We had anguished in isolation for so long, all the while our cosmic seniors watched from not so far away. For hundreds of years, we had not realized there were new friends just beyond the horizon. And so, in secret, we mourned this loneliness: that of what could have been.

In the centuries that have followed we have discovered even more sapient beings around us: the rimor of the Eridani Network, the Xib Zjhar of Xiilu Qam, the pluunima of Niima. We are connected to each other in many ways, but the most important of these is simply that we share the gift of sapience. In this vast and quiet universe, any fellow intelligence is infinitely precious because we are the only ones, as far as we know. Every contact event is first contact, all over again, because every new civilization that we encounter will expand our horizons just enough for us to wonder: "was that last contact? Is there still someone else out there, or is that the end of roll call? Are we alone together, now?"

This, the grandest and most poignant of all mysteries, is why the motto of the Coalition is "solum habemus invicem et stellas" – "we only have each other and the stars."

"We're finally out of the cradle. Of the hundred billion humans who ever lived, we're the first to stand beneath an alien sky."

— CDR Anna Wilson's first words on Mars; Oct. 3, 2018 CE

The Ares program was a crewed spaceflight project led by NASA, in collaboration with other members of the United Nations Aerospace Coalition, that succeeded in its milestone goal of landing humans on the surface of Mars. From its announcement in 2010 it took another eight years of preparation, training, and construction before the first mission was ready to begin.

Ares 1 was launched in mid-2018 and reached the red planet a few months later. At 10:45:33 UTC on October 3rd, 2018, commander Anna Wilson of the United States became the first human being to ever set foot on Mars and the first living thing on the planet in almost four billion years. Ares 1, and the four missions to follow, greatly enriched humanity's understanding of Mars. Ares 5 returned home in early 2028, ending the first crewed Mars exploration phase and opening the door for the next.

The Ares program was the most exciting thing that had ever happened to humankind at the time, and captivated the public imagination for over a decade. Like its predecessors Apollo and Artemis, it is widely recognized across the 30th-century human diaspora as a key reason for humankind's modern status as adept starfarers, best expressed by Commander Wilson in her first words upon touching the Martian surface: "We're finally out of the cradle."

Spy's OCs: Zak Kaiyo

art by my good friend, the wonderful @wildegeist!

Realm: Arcverse Species: Tokaya Homeworld: Terotewaukia (Teroteaumia system) Age: 26 annua (29 Earth years) Gender (human analogue): cismasculine (he/him, xe/xen*) Height: 1.8 m Weight: 72.5 kg Occupation: Captain and pilot of the starship Free Spirit; freelance cargo-hauler; occasional mercenary; jack-of-all-trades [Suggested Listening: Burn Out Brighter by Anberlin]

Zakane "Zak" Kaiyo is the co-owner, captain, and pilot of the heavily-modified light hauler Aum Hara (otherwise known as the "Free Spirit") and the leader of a small band of freelance spacers that make their home aboard the ship. He's just one more spark in the great spiral; one more restless soul trying to make a living doing what he can in a galaxy that's always moving and yet always standing still. From the Tyrian Shallows to the Drift and everywhere in between, Zak and his small but loyal crew of misfits can be found anywhere something interesting is happening.

Zak's talented -albeit reckless- piloting skills earned himself and his copilot Arkto a spot in the Galactic Spacecraft Pilots Association Hall of Fame, having broken the record for the smallest crewed ship by mass to exceed 10 million times the speed of light with a hyperdrive. His performative stuntwork is also renowned, and he frequently attends the annual Galactic Pilot Convention.

Most of the "swashbuckling freelance ace pilot" tropes apply to this space hobo, whose personal creed is "do good recklessly." His confidence, determination, and cheerful sarcasm make for an extremely charismatic, if reckless, leader. He's very mischievous and likes to get into trouble, but can be relied on to get out of it as quickly as he gets into it… most of the time. Zak acts fearless but, go figure, this man has Attachment Issues. He hates the idea of getting tied down to one place or thing, yet at the same time he is fiercely protective of his crew. (Shhh. Nobody tell him.)

Zak's homeworld is a backwater: connected to the galaxy and participant in its affairs, but hardly anyone there actually got out beyond the system. He was constantly told that he ought to be happy on Terotewaukia, fixing up interplanetary haulers and maybe going to the outer moons of the system once in a while. He and his two best friends always wanted more. The three of them had plans to quietly fix up one of the written-off hauler derelicts on company time and get the hell out, making their way around the wild starry yonder to see what could be seen.

And then one of them decided they wanted to stay and settle down.

That was the last straw for Zak. As soon as the opportunity arose, he and Arkto (his other bff) took off in their souped-up light hauler and never looked back. But once they were out there... Zak came to realize that the galaxy isn't a really adventurous place.

See, Arcverse is a universe that everyone thinks has been more or less figured out. Galactic civilization has been around for something like a million years or so, and the Arcadian Order have been sort of running the Galactic Assembly for about that long (mostly because they got off their planet first and they do a pretty decent job of wrangling the rowdier civilizations with diplomacy). The entire galaxy is, broadly speaking, at peace. The clash of titans already happened; the fate-of-the-galaxy-level stakes were sorted out thousands of generations ago. All the major starfaring powers, while independent in principle, are constrained by the bureaucracy of the Galactic Assembly. There's mild internal turmoil —and there's always an underbelly— but it's still quite tame. There's a whole galaxy out there with lots to see but nothing to really strive for in it.

Zak Kaiyo is someone who desperately, fundamentally, needs to strive. He wants to live fast and die young in a galaxy where everyone lives at a reasonable pace and dies basically never. He exists to challenge the stagnancy of a world that's as close to utopia as it can reasonably be. Zak wants so badly to save the galaxy, but he lives in a galaxy that doesn't need saving. And that's tearing him to pieces.

An alien desires to 'court' another alien, of the race called humans. The human is desirable in every way: talented in multiple skills, professional and domestic, with soft, squishy flesh and an eagerness to learn - the alien could go on and on, but people complain when the alien talks about their 'crush', as other humans call it

The problem is, the alien's species relies on scents and pheromones for communication. Their first meeting with the human was during a crisis, and their natural scent was strong, sweat mixing with that fabled human instinct to survive with all members of their extended pack alive, too. No other human smelled quite like this one. It sent the alien's hearts a-flutter, and shivers through their many wings.

But now? The human smells different, and not in a normal human way. One week, citrus and palm fruits from the black jungles of the planet Cerib. Another week, exotic vanilla from their origin planet, with something warm and spicy the alien can't place. Lavender and honey from Blackcurrant bees. Something juicy like apples. Something this, something that, and they're all beautiful scents - but it's not the human's scent, and they can't really smell their emotions through it. Frustrating.

One day, the alien sulks, watching their desired one rush past, tablet in hand. They smell like sweetened coffee and chocolate - the latter a romantic treat to humans, and a reminder of how far they are from that romance to the alien. The human next to them breathes in the scent, and smiles.

"Man, (name's) got some great perfume on today," they say.

The alien lifts their head. "Perfume?"

A little research later, and things suddenly make sense. They'd heard about perfume before, the human wasn't the only one to wear scents, but they'd been so lovelorn they hadn't used their brain. But that wasn't important. What mattered was that humans used perfume and similar products to draw in desired partners.

Two can play at that game.

Three days later, the alien walks in to their normal location. To their surprise, the human their hearts are set on rushes towards them, calling their name.

"I'm so sorry!" They apologize. They aren't wearing any scents today. "I didn't realize my perfume might be messing with your senses. I've switched it out with another type that you'll find easier to deal with. I was just trying to..."

They trail off. The alien waits, hopeful. A new scent spikes from the human.

"Is that... Cinnamon?"

"With a little bit of Ophelion flower, and Soljoiner lemon," the alien says, smiling like the humans do. "I got inspired by your choices."

A hesitation. "Do you like it?"

The human breathes in deep. From them, now the alien can sense what they've wanted. Interest.

"You smell amazing," the human says. The glow in their eyes as they look at the alien, well, the alien adds that to their list of all the reasons they want the human as a partner.

"Are you sure you know what you're getting into?" Another alien says later, at the communal garden. "Humans are hardcore."

The alien looks across the way to the human of their hearts. They are smiling, they smell a bit like the alien now, from their hug.

"For that one? It's worth it."